Belmont Perry: The First Civil War Autograph Collector

Autograph collecting in the United States reached its peak during the 1880s. Like the carte de visite craze of the 1860s, Americans collected autographs of their favorite celebrities or heroes. According to historian Lester J. Cappon, the Civil War led to “a new cluster of heroics to inspire Americans and a fresh supply of manuscript merchandise…”[1] But unlike a mass-produced portrait, a hand-written note with an original signature was a one-of-a-kind item. Autograph collecting became a popular hobby for some Americans, but for others, like Belmont Perry, it was an obsession.

The Woodbury, New Jersey, lawyer spent over three decades amassing hundreds of Union and Confederate Civil War generals’ autographed letters, portraits, or other ephemera. He wrote directly to the generals (those still living) or their friends or relatives to obtain them. He wasn’t afraid to use unconventional methods to secure what he desired, either.

Perry reportedly feared that some Confederate generals might ignore his request, so he claimed that he was a historian compiling a pro-Southern book on the history of the war. For the Union generals who were reluctant to comply, he apparently said he was writing a book on the role each played in winning the war. But the worst offense Perry was accused of was never mailing back letters he promised to return after copying them.[2]

Perry’s interaction with Confederate major general James Patton Anderson’s widow demonstrates how persistent and manipulative he could be to add to his collection. In January 1881, he wrote to Henrietta “Etta” Anderson saying that he planned to publish a biographical work and had compiled a collection of autographed letters and orders which he bound into six volumes. He left two pages blank in one volume so that he could attach manuscripts from General Anderson. “Could you not lone me one of them for this purpose — that is the paper to remain in this collection but as your property & subject to your order?” he asked. He proceeded to tell the Confederate widow that “Where ever I have found the friends or relatives possessed of such papers they have readily complied, & I cannot see why anyone should object to your forwarding me one of those reports under those conditions.”[3]

In June 1889, Perry wrote again requesting that Etta respond to a letter he sent in November 1888 about acquiring a photograph of the general. Mrs. Anderson replied in July, revealing that she had two portraits of her late husband — one in a Confederate uniform and one taken before the war.[4] In December 1889, Perry mailed another letter. “I have a fine collection of portraits, etc. of the Confederate Generals in my private library and prize them very highly indeed & regret very much not having one of your brave and chivalrous husband,” he told her, “for so such I know, by the truths of history, that he was.” Perry asked Etta to send whichever image presented the best likeness of the general and requested for her to cut his signature from a letter or flyleaf of a book and attach it to the portrait.[5]

But Anderson’s relatives were reluctant to part ways with one of the few photographs they had of him. On February 20, 1892, Perry wrote a snide letter to General Anderson’s son, Theophilus. “I desire greatly to procure a photograph of Genl. Patton Anderson. What reason can exist why you should not aid me?” he demanded. “If you will loan me a photograph of him I’ll have it copied & return it to you. Is that an unreasonable request?” Perry claimed he would deposit any amount of money in Palatka’s bank or in the hands of any leading attorney in the city until he returned it to the family. “I’ll comply with any condition you name,” he pleaded. “Remember I’m simply asking for the temporary loan of a photograph.”[6]

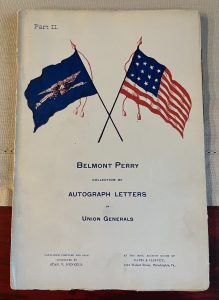

In January 1899, Belmont Perry moved to Pasadena, California, in hopes that it would relieve his poor health. He liquidated many of the artifacts he had collected over the years, including one of the most impressive Civil War autograph collections ever compiled.[7] In May, Davis & Harvey Auctioneers displayed the collection at its auction rooms at 1112 Walnut Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Auctioneer Stanislaus V. Henkels divided the collection into four separate categories: Confederate generals, Union generals, Confederate statesmen and bishops, and a miscellaneous lot. The auctioneer had a limited number of the catalogs printed. They were too heavy to mail, so he had copies delivered to select addresses listed in The Publishers’ Weekly. Copies could also be ordered by prepaid express. “The catalogue was well made and should be in the hands of every Civil War collector,” editor Walter R. Benjamin wrote in the June 1899 edition of The Collector.[8]

The auction began on May 4 and lasted for three days. “The attendance at the sale was light,” Benjamin indicated, “and bidding was rarely spirited.” The letters of Confederate generals kicked off the auction and sold well — especially the war letters. For instance, an 1864 ALS (autographed letter signed) from James Patton Anderson sold for $9, while an 1848 letter from Lewis A. Armistead sold for $8. (The Anderson letter was probably the one Perry received from Etta Anderson.) “These prices are simply astounding,” Benjamin stated. “It will be a revelation to certain collectors who think Civil War matter is not worth collecting.”[9]

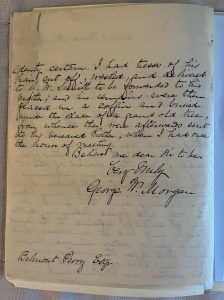

The autographed letters of Union generals did not do as well. “Letters written before or after the war seemed to be in no demand,” Benjamin declared, “and the great majority of them went at 25 cents each to one buyer.” However, some did sell well, such as an 1865 DS (printed document with signature) from George A. Custer, which sold for $7.50. Also, a buyer purchased an 1865 ALS from George H. Thomas for an impressive $21. One of the more interesting pieces of memorabilia sold in the Union generals lot was an autographed copy of Ulysses S. Grant’s “Unconditional Surrender” letter to Simon B. Buckner during the Battle of Fort Donelson.[10]

The third lot consisted of Confederate statesmen and bishops autographed letters, which generated little interest among buyers. The auctioneer couldn’t give away the Episcopal bishops autographed letters. They auctioned off the photographs of Union and Confederate generals in two lots — the former at four cents each and the latter at five cents each. The fourth and fifth lots consisted of other material from Perry’s collection, ephemera Henkels accumulated over time, and the Gerard Bancker papers. A buyer purchased a book with George Washington’s signature for $102.50, while an Abraham Lincoln ALS sold for $22.[11]

It’s unclear how much Perry profited from the auction. He lived the remainder of his days in California. He ran a newspaper and a law practice and served as chairman of the New Jersey Democratic State Central Committee for Woodrow Wilson.[12] On October 5, 1912, the autograph collector died in Pasadena, California, and his remains were returned and buried in Woodbury, New Jersey.[13]

Like him or hate him, Belmont Perry assembled one of the most impressive collections of Civil War generals autographed letters at the time. There are Civil War collectors today that undoubtedly have even more impressive collections, but Perry’s remarkable dedication (perhaps obsession) permitted him to amass a collection before antique shows, Facebook buy/sell/trade groups, and eBay made it easy for modern collectors. He did it the old-fashioned way: by pen and paper, albeit by adopting questionable tactics. Who knows, you might even have a piece of Belmont Perry ephemera in your collection. I was surprised to find out I did.

[1] Lester J. Cappon, “Walter R. Benjamin and the Autograph Trade at the Turn of the Century,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 78 (1966): 21-22, 25, 30.

[2] Simon Gratz, A Book About Autographs (Philadelphia: William J. Campbell, 1920), 31-33.

[3] Perry Belmont to Etta A. Anderson, January 4, 1881, Woodbury, New Jersey, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

[4] Perry Belmont to Etta A. Anderson, June 24, 1889, Woodbury, New Jersey, George A. Smathers Libraries.

[5] Perry Belmont to Etta A. Anderson, December 28, 1889, Woodbury, New Jersey, George A. Smathers Libraries.

[6] Theophilus B. Anderson to Perry Belmont, January 3, 1890, Palatka, Florida, and Perry Belmont to Theophilus B. Anderson, February 20, 1892, Woodbury, New Jersey, George A. Smathers Libraries.

[7] “Things Talked About in the County,” Gloucester County Democrat (Woodbury, NJ), February 2, 1899; “Jerseymen in California,” Gloucester County Democrat (Woodbury, NJ), January 10, 1907; “Valuable Relics: Part of Belmont Perry’s Large Collection,” Woodbury Daily Times (Woodbury, NJ), January 12, 1899.

[8] “Autograph Letters Sold,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), May 5, 1899; The Publishers’ Weekly (New York, NY), March 25, 1899; Walter R. Benjamin, ed., The Collector: A Monthly Magazine for Autograph and Historical Collectors 12, no. 9 (June 1899): 105.

[9] Benjamin, The Collector, 105-106.

[10] Benjamin, The Collector, 106.

[11] Benjamin, The Collector, 106.

[12] “Belmont Perry,” Lambertville Record (Lambertville, NJ), October 11, 1912; “Belmont Perry Dies in West,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), October 6, 1912; “Judge Belmont Perry Dies of Apoplexy,” Denver Post (Denver, CO), October 6, 1912.

[13] “New Jersey Jots,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), November 13, 1912.

Wow — what a fascinating essay … i enjoyed reading about old Belmont and then scrolling down to see where the heck you found all this great stuff … i can’t imagine how letters from a New Jersey lawyer who moved to California found their way to the University of Florida, but they did … thank goodness for the archivist who decided to save this stuff so you could find it 100+ years later!

It was also very cool that you tracked down the results of the auction in the Philly, NJ and NYC papers and the autograph collectors magazine — pretty slick detective work … and there were some neat letters in the auction — especially the Grant to Buckner note (albeit a copy) at Fort Donelson … i was also struck by Belmont’s apparent renown as he had obits in CO and DC newspapers.

thanks again for this wonderful piece.

PS – back in 1990’s, i was an aide to a Navy admiral and we would routinely get letters from collectors asking for an autographed photo of the admiral … folks are still collecting.

I have a letter from Henry McIver to Belmont Perry from 1896. At the time, Henry McIver was Chief Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court. McIver had been a delegate from Chesterfield County, SC to the South Carolina secession convention, the results of which ultimately led to the Civil War. McIver’s law partner in Cheraw, SC, John Inglis, has long been considered the alleged author of the Ordinance of Secession. In the letter (on SC Supreme Court stationary) to Perry, McIver answers Perry’s inquiry as to whether he could direct Perry to other signers of the Ordinance of Secession. Over three pages, McIver lists various signers and what he knew of their status or to whom Perry could direct his inquiries. I’m a lawyer and a Chesterfield County, SC native, so this document is fascinating and one of my favorite acquisitions. I appreciate your post tremendously as it helps me understand the context of the letter.