“I Don’t Like to Engage in What-Ifs, But….”

If I had a nickel for every time I’ve heard someone say, “I don’t like to engage in ‘What-Ifs…’” and then launch themselves into a discussion about a “What If,” I could’ve funded the upcoming ECW Symposium on What Ifs out of my own pocket. I heard it happen again this week.

For the record, I don’t criticize people for doing that. One of my whole arguments is that we just can’t help ourselves. We all love to play armchair general. It demonstrates how active history can be when we love it and engage it and the questions it offers.

Here’s what happened:

I had the pleasure of speaking at the Chambersburg Civil War Seminar this week. It’s an old and venerable Civil War symposium based out of Chambersburg, PA, although this month, they took their show on the road and came to the Fredericksburg area to talk about Chancellorsville. I was there to talk about the last days of Stonewall Jackson (or, as we often say, I was there “to kill off Jackson”).

The discussion of which I speak didn’t pop up as a result of my talk, though. I was the last speaker before lunch, so folks were ready to eat! (No one likes being the person standing between a room full of hangry people and their meal.)

Rather, I was listening to the Q&A of the speaker before me, my friend and colleague Eric Wittenberg. Someone had asked him what the outcome might have been had someone more aggressive and competent been named commander of the Union cavalry instead of Alfred Pleasonton. Pleasonton got the job because of the poor performance in the campaign by George Stoneman.

“I don’t like to engage in the What-Ifs,” Eric said in his response, “the main reason being that there’s so much to know about what really happened that there’s always still something for to learn and understand.”

But then, as if he couldn’t help himself—and, again, let me stress, I don’t fault him, and I relay this with a chuckle—he went on to say that the question of cavalry leadership is one that has always intrigued him. He went on to speculate about a younger, more aggressive, more competent commander in Pleasonton’s place.

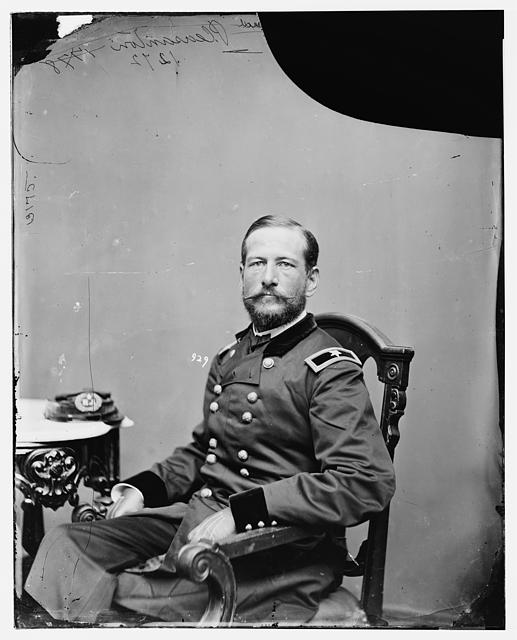

Eric gave particular attention to George Dashiell Bayard, mortally wounded at the battle of Fredericksburg. Had Bayard lived, Eric contended, he would have made an excellent candidate for cavalry command. At 26 years old, Bayard had already been promoted to cavalry commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Left Grand Division and had a promising future ahead of him. Robbed of such young talent, the army turned to Pleasanton, who had a talent for self-promotion that far exceeded his talent as a cavalry commander.

Eric then went on to wonder aloud about the impact a different cavalry commander would have had going into the Gettysburg campaign. Would George Custer and Wesley Merritt have advanced as they did or played the important roles they eventually did? Eric offered no answers because, as he said, the questions were unanswerable, but they provided great fodder for thought.

No sooner did Eric wrap up his answer than the next questioner said, “Speaking of the ‘What-Ifs,’ let’s go there.…” Again, it’s like people just can’t help themselves! The questioner went on to ask a question about George Stoneman crossing the Rappahannock and Rapidan as originally planned rather than after a rain delay

Joe Hooker’s original plan called for Stoneman’s cavalry corps to strike south by April 15, but Biblical rains flooded the rivers, which made crossing the rivers impossible and which would have cut Stoneman off from the rest of the Army of the Potomac if he found himself in quick trouble. So, Stoneman’s raid launched on April 29, instead, even as portions of the Army of the Potomac rumbled across the river with him. When Stoneman crossed at Kelly’s Ford, he was preceded by the XII, XI, and V Corps, with other corps using other river crossings to the east.

The question about Stoneman’s timing gave Eric the chance to talk more about Confederate cavalry dispositions early in April and how they compared with dispositions later in the month. That provided an opportunity to look at the possible options Stoneman might have faced, although Eric wisely avoided gaming out those scenarios because, as he’d said, they’re unanswerable.

As I mulled over the question myself, I started looking at Stoneman’s performance. Was there anything in his raid that suggested he would have moved with any more alacrity had he started earlier? In other words, would an earlier start have made him move faster? I didn’t think so. What actual evidence would have supported that hypothesis?

Of course, to cross the river sooner would’ve meant no torrential rain storm in the first place. That falls outside the boundaries of useful counterfactual speculation because, after all, we can’t change the weather. A change of weather in April 1863 would have meant an entirely different Chancellorsville campaign because the timetable for Hooker’s entire plan would have moved up by a couple weeks, and it would be impossible to game that out because of all the different moving parts.

Asking a couple simple questions led to a tremendous amount of fruitful rumination. It made me, Eric, and attendees in the room reexamine what we did know, what other evidence we might have to look at, and what the limits of our assumptions might be. We never answered anything definitely, but we better understood the scenarios we were asking about.

That’s good thinking, all the way around.

————

You’re welcome to join in next weekend—a couple tickets remain—as we ponder Great What-Ifs of the Civil War at the Eighth Annual Emerging Civil War Symposium at Stevenson Ridge. Click here for details and to reserve your space.

Both you and Kris gave great talks. Well done.

Thanks!

What is the percentage of “what if” questions do audiences pose during question and answer sessions. I’d like to know so I’m prepared, what if I ever speak about the Civil War in front of people.

To clarify, what percentages of questions asked by audiences are of the “what if” type. Thanks

My experience, you’ll usually get one every talk or two. Depends on topic though – some of the lesser known topics I cover don’t often get them.

I agree with my Polish brother: usually 1 or 2. Some topics tend to invite them. For instance, whenever I talk about Jackson’s last days, I almost ALWAYS get a couple what-ifs. Gettysburg topics tend to draw them out, too.

I see what-if questions as a mark of success, to be honest. My goal as an interpreter is to provoke thought, and someone asking “What if” suggests that I’ve gotten them thinking about something.

General Innis Palmer is someone who could have played a more prominent role in cavalry operations in Virginia. He was a senior captain in the 2nd US Cavalry Regiment before the war and spent most of the 1850s fighting the Comanche and scouting in Texas. He commanded the US Cavalry brigade at First Bull Run. However, he spent most of the war commanding infantry in North Carolina. I guess someone had to. He is promoted to colonel of the 2nd US Cavalry Regiment in 1868 and retired 11 years later.