What If…John Pope Had Invaded Canada?

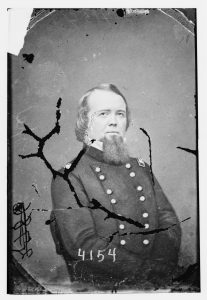

Many ECW readers will know (and perhaps take delight in the fact) that Major General John Pope was banished to Minnesota in the wake of his disastrous defeat at the battle of Second Bull Run. President Abraham Lincoln asked Pope to go west and oversee the aftermath of what Civil War-era Americans termed the “Dakota Uprising.” Scholars today view the events of the late summer of 1862 as a far more complex event than nineteenth-century Americans. Historians now opt against incendiary language like “uprising” or “massacre” and prefer to see the resistance movement of Mdewakanton Dakota leader Little Crow as a strike against American expansion and a significant moment in Native American resistance to US settler colonialism.

Reevaluating language is one way that scholars have sought to resituate the events of the late summer of 1862 within the broader context of the Civil War. Another has been to look at the theater inherited by Pope as a zone of military crisis and contestation. Had Pope gotten his way, it may also have been a site for turning the war between North and South into an international conflagration. Because, in his effort to respond to the successful resistance of Little Crow and his adherents, Pope proposed invading Canada, pursuing the Native peoples who had evaded capture and a military tribunal. Pope believed that crossing the border would put an end to Native American threats to white settlements in Minnesota and the Dakota Territory, by demonstrating that international borders would no longer function as deterrents to US military power. Fortunately for Pope (and his already suspect military reputation), the arguments against such an action were equally compelling and Pope stayed put on the southern side of the 49th parallel.

Reevaluating language is one way that scholars have sought to resituate the events of the late summer of 1862 within the broader context of the Civil War. Another has been to look at the theater inherited by Pope as a zone of military crisis and contestation. Had Pope gotten his way, it may also have been a site for turning the war between North and South into an international conflagration. Because, in his effort to respond to the successful resistance of Little Crow and his adherents, Pope proposed invading Canada, pursuing the Native peoples who had evaded capture and a military tribunal. Pope believed that crossing the border would put an end to Native American threats to white settlements in Minnesota and the Dakota Territory, by demonstrating that international borders would no longer function as deterrents to US military power. Fortunately for Pope (and his already suspect military reputation), the arguments against such an action were equally compelling and Pope stayed put on the southern side of the 49th parallel.

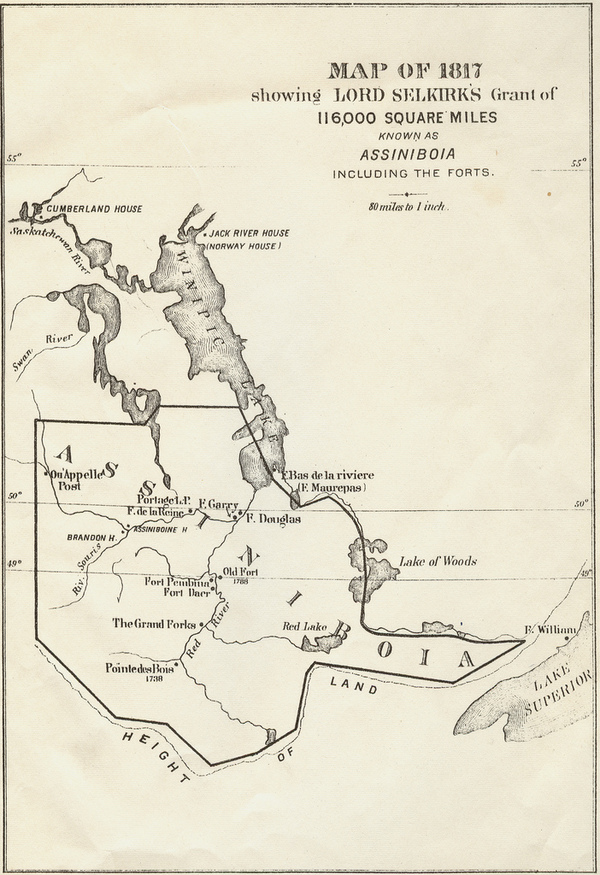

In May of 1864, the Member of Parliament for King’s County, Ireland rose in the House of Commons to deliver a speech on the “Outrages by Sioux Indians” taking place in the Red River settlement of Canada. The settlement—what is today the Canadian province of Manitoba—like all of Canada in 1864, remained under the direct control of the British government.

The speech that John Hennessy delivered emphasized the difficulty Indigenous incursions into the Canadian settlements might cause the British government. The MP predicted depredations that might result in thousands of men, women, and children killed. In spite of their exaggerated fears, the British government also realized that allowing the United States Army to invade and occupy the British possessions would set an undesirable precedent and leave their far western territories. Despite wanting to help the citizens of Canada, Hennessy urged his government not to leave their Canadian provinces, “at the mercy of a foreign soldiery.”[1]

Indigenous use of the border between the United States and Canada laid bare the delicate balance of international power on the North American continent. Historians have long argued that this balance of power was endangered by the Civil War, particularly in Mexico, where a wary eye was always trained Napoleon III’s French puppet government. The results of a war with the British in Canada, provoked by Native actions, would likely have major ramifications for the future of the North American continent.

The citizens of British North America had their own concerns about the effect the Civil War would have on their territory. If the Confederacy succeeded in establishing an independent nation, “the North [might] seek compensation in the conquest of British America.”[2] If the Union succeeded in putting down the Confederate rebellion, the prospects were not any more encouraging. British North Americans that the victorious Union “might attack the provinces in order to employ war-hardened troops, to complete the work of Manifest Destiny.”[3] The prospect of Union victory convinced many that the restored United States would have the resources to dominate the continent and exclude British North America from trans-Atlantic (and trans-Pacific) trade.

But the officials on either side had little recourse. Indigenous use of the border had only increased after the events of 1862 and left policy makers and military officials grasping for options. Secretary of State William H. Seward sent a brief letter to Lord Lyons, the minister to United States from Great Britain, on January 12, 1863, “with a view to prevent, if possible, hostile Indians residing on either side of the frontier from being supplied with arms, ammunition, or military stores, to be used against the peaceful inhabitants of the United States.”[4] The letter helped little. General Henry H. Sibley wrote from St. Paul on January 25, 1864, that “the hostile Indians are directly aided and abetted by Her Majesty’s subjects.” He told the commander of the Department of the Northwest, General John Pope, that he hoped that a “professedly friendly power shall not longer permit its soil to be a convenient refuge for these Ishmaelites of the prairies.”[5]

The British had offered to provide subsistence and supplies to the Indigenous refugees, on the condition that they should only be used for hunting game—and that the Natives would return to the American side of the border. Governor Alexander Dallas, of the Red River Settlement, hoped for a speedy evacuation from his province. Dallas’s requests to London for regular British troops to defend the border had been denied—and he could not protect his constituents without aid. And yet, when the governor met with his council on January 24, 1864, he was forced to report that the Santee “had gone no further than White Horse Plain, with the avowed intention of remaining there.” Dallas further reported that he was “now disposed strongly to doubt, whether, they had really ever intended to leave the Settlement this Winter.”[6]

As Dallas fretted, Pope proposed to send US troops across the border after the Santee. Despite the perceived threat coming from Canada, both General in Chief Henry Halleck and President Abraham Lincoln were less than inclined to agree to the plan. In response to a request for instructions on the situation, Halleck informed Pope: “The President directs that under no circumstances will our troops cross the boundary line into British territory without his authority.”[7] Though by 1864 British intervention on behalf of the Confederacy no longer seemed likely, Lincoln still urged caution when it came to the war’s international aspects.

John Pope wanted to invade Canada. His wishes were denied. But “What-If” he had gotten his way? Several potential results come to mind. First, the British may have reevaluated their position vis a vis neutrality. Second, had the Americans been adamant about the need to pursue the Santee across international borders, the British Crown may have been forced to provide troops to support the mission or to protect their own citizens from a foreign invader.

And, had the British actually sent support to their western Canadian frontier, the British citizens living in Canada may have been contented with the idea that Parliament had their safety and security at heart. One of the primary reasons that British Canadians pursued Confederation and greater independence from Great Britain in 1867, after all, was the failure of the Crown to provide for its North American settlers, in their moments of greatest danger.

[1] HANSARD, House of Commons Debates, May 3, 1864, Volume 174, Reference Number cc2053-5.

[2] W.L. Morton, “British North America and a Continent in Dissolution, 1861-71,” History, Volume 47, Issue 160 (January, 1962):148.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Message of the President of the United States, and Accompanying Documents, to the Two Houses of Congress, at the Commencement of the First Session of the Thirty-Eighth Congress (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1863), 492.

[5] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 127 vols. index and atlas [Washington: GPO, 1880-1901], ser. 1, 34[2]:152-3

[6] Edmund Henry Oliver, ed., The Canadian North-West, Its Early Development and Legislative Records; Minutes of the Councils of the Red River Colony and the Northern Department of Rupert’s Land (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1914), p. 533.

[7] O.R., 22[2]:211.

Although historians credit the Charlottetown Conference held in September, 1864, initally consisting of delegates from New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island (PEI), to eventually lead to discussion of the union of British North America, as prompted by the fear of U.S. military retaliation after the St. Albans Raid by escapted Confederate POWs from Canada. However, the Raid occurred in October, 1864, so the threat of Pope crossing the international border may have been the initial catalyst for the Charlottetown Conference, after the Trent affair, the first step to Canadian Confederation that eventuially occurred in 1867. Incidentially, the room in the provintional capitol in Charlottetown, PEI, where the Conference was held has been preserved as it was in 1864.

Good post! Here in Maine, politicians worried about Britain invading the state (at least that portion east of the Penobscot River) in 1861 and 1862 and expressed some fears that Britain would try to capture Portland.

Never would have happened as Queen Victoria had already decided Great Britain was to remain neutral. Her husband , Prince Albert had been very influential in helping to de-fuse the Trent Affair.

The best book on this is…Southern Strategies, edited by Christian Keller of the Army War College. It is a good read.

What historians believe there was not a massacre of white settlers in Minnesota in 1862? Whatever legitimate grievances the Dakotas may or may not have had, no one can deny they massacred many hundreds of settlers, including women and children. See the recent book, Massacre in Minnesota by Gary Anderson. Historians do themselves no favor by whitewashing history.

Hi John,

Thanks for taking a look at my piece. I just wanted to pop on and say that while the use of language is hardly the focus of my essay, which is about international affairs during the Civil War, it is worth noting that historians change their language because the job of the historian it not to replicate the perspectives of the past. Instead, we seek to interpret and reframe them in ways that help us all gain understanding of how things changes.

To use the term “massacre” in this case is to suggest that the actions were unjustified and also would lead many to believe that there was no retribution carried out by the United States. I believe it is important that the language we use to teach and write about these events does not simply portray a single perspective — and that is not whitewashing history.

In fact, analyzing language is how we can learn that settlers in 1862 carefully chose how they described the events of that summer to gain political and financial support for accelerating Dakota removal and receiving federal compensation for any losses they suffered during the conflict. Just because they called it a massacre does not mean we have to, or indeed, that we ought to.

Anderson’s book, provocative title aside, actually makes the case it was the Americans, not the Dakota, who were committing ethnic violence at a minimum or genocide at worst. Titles, very often, do not tell the whole story.

If you would like to know more about why and how language surrounding these events has and continues to evolve, I highly recommend the the resources and information available from the University of Minnesota’s Holocaust and Genocide Studies Center, which has done extensive work on the events of 1862 and the ways they were memorialized.

And you certainly do not have to agree with me, but I thought, since several comments seem upset that I mentioned shifting language regarding these events, a response might at least give a sense of how I approach these questions as a historian.

Thank you, Cecily, for your thoughtful and extended explanation. I sincerely appreciate your doing so and not hiding behind a wall of silence. But, yes, we have to disagree. No amount of explanation defending the Dakotas’ actions will in my mind sanction the torture, rape, and murder of innocent men, women and children. Whatever justification or excuse their defenders put forward for the Dakotas, it was still a massacre on a grand scale. To say otherwise is to sanitize what happened. It also explains why many in this country look skeptically at such new interpretations of history.

thanks for your great essay … i had no idea there was chatter between Pope and Halleck about pursuing the Sioux across the U.S. and Canada border … perhaps a big plus for the legacy of the hapless General Pope is he had the good sense to ask for permission … and the response leaves no doubt about the President’s wishes — “… under no circumstances will our troops cross the boundary line … ” so, it’s hard to imagine a “what if” here.

i have also noticed the softening of lingo regarding the use of massacre, which i find ahistorical and downright silly … the word itself simply implies “the act or an instance of killing a number of usually helpless or unresisting human beings” … that’s what happened to the “helpless” farmers in their Minnesota fields and the “unresisting” American Indians massacred by the U.S. Army at Sand Creek.

If John Pope had invaded Canada the Confederacy would have won the war with British help and Pope would have been defeated by whatever scratch force Canada could have raised against him.

This is why Lincoln was so stern in forbidding such a mad move.

I have read that between 40,000 and 50,000 Canadians (from Upper and Lower Canada, and the Maritimes), and more than 50,000 British citizens (probably mostly from England, but surely also some from Scotland and Wales) served in the Civil War. Apparently most of these served on the Union side. Many crossed over the border to enlist, although many would have already been resident in one of the states, even if unofficially (not an uncommon status at the time). I have not researched these numbers, but if true then it raises the question of what effect an invasion of Canada would have had on them, and vice-versa. There may have been a mixed reaction among them to another American invasion of Canada.

Also, I have read that more than 150,000 Irish also served, more in the Union army than in the Confederate. The same question applies to that number, perhaps in a different way if one assumes that most of the Irish who had come to the United States would not have had much love for Great Britain.

So, would there have been dissent and resistance, within the ranks of the Union army, to such an invasion? I have no idea. Any thoughts on this?

Taylor has just added 250,000 British and Canadian citizens to the U.S. forces. I would be very careful about accepting this figure.

Good point, and shows that more research could be done about this. I was just commenting based on what I had read.

Not all served in the Union forces though.

I also have doubts about the stated number of Irish, although it is known that many Irish did enlist.

Moreover, although it has been said that about 50,000 “British citizens” (whatever that means) crossed the Atlantic to serve in the war, I wondered whether that account included many of the British subjects in Upper and Lower Canada (as the areas were then referred to) and the Maritimes, who were already resident in North America at the time. What I read seemed to refer to residents, but it could be open to interpretation.

I also wondered if some of the Irish, in particular from the north of Ireland, were included in the category of British “citizens.”

Clarification. What I read did not seem to refer to residents in discussing the British who came across the Atlantic to serve in the war.

I don’t know if a memorial in Canada to the Canadians who served in the Civil War refers only to longer-term residents or whether it includes British subjects who had only recently arrived from the mother country. I am under the impression that immigration control and categorization, if you were from Great Britain and arriving in Canada, was pretty loose in those days.

https://books.google.com.au/books/about/The_Civil_War_Years.html?id=PF-4P0zOKSoC&redir_esc=y

https://www.amazon.com/Canadians-Civil-War-Claire-Hoy/dp/1552784509

https://www.amazon.com/Blood-Daring-Canada-Fought-American/dp/0307361462

https://www.amazon.com/Canadas-Governors-General-1847-1878-Constitutional/dp/0802090613

https://archive.org/details/reporttofreedmen00howe

https://archive.org/details/cihm_91059

https://archive.org/details/cihm_47542

https://archive.org/details/cihm_16958

A number of resources pertaining to Black American settlers and fugitive slaves in what is now Ontario, (mainly), and the Underground Railroad:

https://archive.org/details/cihm_47542

https://archive.org/details/cihm_55469

https://archive.org/details/cihm_55469

https://archive.org/details/cihm_91059

https://archive.org/details/cihm_25950

https://archive.org/details/cihm_25950

https://archive.org/details/cihm_91059

I sent this one to Christy Coleman as a thank you. She was very nice in our email exchanges.

https://archive.org/details/cihm_47542

https://archive.org/details/cihm_55469

https://www.amazon.com/Queens-Bush-Settlement-Pioneers-1839-1865/dp/1896219853

https://archive.org/details/reporttofreedmen00howe

http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/microfilm/provincial_freeman.aspx

‘The Provincial Freeman’ newspaper

‘Shadow & Light’, by M.W. Gibbs, the brother of Thomas Clarkson Gibbs.

M.W. Gibbs was an associate of Frederick Douglass and like Martin Delany and Thomas Morris Chester, was an advocate of Black Colonisation, (this is one of my fave historical topics pertaining to the CW/WBTS and easily one of the least adequately understood in our times).

He and a fair number of other Black Americans emigrated to the British colony of Vancouver Island, (which was a separate colony from British Columbia until 1866, and their joining was directly due to the war). He became among the first Black Americans openly elected to public office in North America in 1866 for the city of Victoria. A couple years later, he returned to America to take a Reconstruction position in Arkansas.

“…General Grant’s campaign [to Richmond] ended in the surrender of General Lee, and Peace, with its golden pinion, alighted on our national staff.” – page 79.

https://archive.org/details/shadowandlighta00gibbgoog/page/n117/mode/2up

One man who made two significant speeches re. the War,

George Brown of Canada West, (present-day Ontario):

Editor of the Toronto Globe,

Father of Canadian Confederation, (key drafter of the British North America Act of 1867),

Founder & President of the Canadian Abolitionist Society since its founding in 1851.

3 February 1863, Speech to the Abolitionist Society of Canada,

http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/quebechistory/encyclopedia/GeorgeBrownonslavery.html

George Brown, Speech upon the final drafting of Canada’s original constitution, ‘The British North America Act’, 7 February 1865,

https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/mli-files/pdf/MLIConfederationSeries_GBrownSpeechF_Web.pdf

Some very interesting contemporaneous observation on the war by the Fathers of Canadian Confederation.

See pages 26-47, esp. 42-45. Speakers include, but not limited to-

George Brown & Sir John A. MacDonald of Canada West, (present-day Ontario)

Sir Charles Tupper of Nova Scotia

Frederick Chandler of New Brunswick

Canadian Historical Review, 1920, Vol. 1

https://archive.org/details/sim_canadian-historical-review_1920-03_1_1/page/46/mode/2up

Same historical journal, different copy.

See article beginning on page 255

https://archive.org/details/sim_canadian-historical-review_1920-09_1_3/page/254/mode/2up?q=secession

Further contemporaneous observation on the Civil War/War Between The States from the north.

Sir John A. MacDonald’s observations on pages 42-45 are particularly interesting. It ought be remembered that he is stating his convictions.

https://archive.org/details/unionbritishpro00whelgoog/page/n59/mode/2up

Some more interesting such observations.

https://archive.org/details/cihm_23468/page/n25/mode/2up?q=civil+war

Lastly, although this depicts events a few years after General Pope’s conception to invade Canada, see what a special group of Canadians sent word to America, about any plans with interfering with Canada’s sovereignty.

RIP, ‘Tatanka’…

https://www.amazon.com/Sitting-Bull-Canada-Grant-MacEwan/dp/0888300735

‘Soldiering in Canada’ by George T. Denison.

See contents.

https://archive.org/details/ajl3759.0001.001.umich.edu/page/VI/mode/2up

‘Our Garrisons in The West’,

by Francis Duncan.

https://archive.org/details/cihm_34628/page/n11/mode/2up

Military reminiscences of the civil war

by Cox, Jacob Dolson

https://archive.org/details/cihm_05269/page/n5/mode/2up?q=canada

Confederate operations in Canada and the North; a little-known phase of the American Civil War

by Kinchen, Oscar Arvle

https://archive.org/details/confederateopera0000kinc

In Armageddon’s shadow : the Civil War and Canada’s Maritime Provinces

by Marquis, Greg

https://archive.org/details/inarmageddonssha0000marq

Three Months in the Southern States, by Col. Arthur Fremantle.

He makes mention of a high number of Nova Scotians; these were involved in shipping Confederate cargo out of Mexico, pages 20-21

Just spent the entire afternoon, Central Australian Standard Time, reading this treasure trove of information by the Coldstream Guards’ LtCol Fremantle. Meetings with (and impressions of) many Civil War personalities are recorded, including Generals William Hardee, Leonidas Polk, Joseph E. Johnston, States Rights Gist, John B. Magruder, Braxton Bragg, and banished Northern Congressman Clement Vallandigham.

Thank You!

Attached is the link to a similar resource: “My Diary, North and South” by Times of London journalist William Howard Russell. Reporter Russell met some of the same personalities as Colonel Fremantle, and their impressions can be compared: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t6d229r63&view=1up&seq=11&skin=2021

thank you for bringing this fantastic source to light!

I also like the memoirs of Johann Heros von Borcke.

It’s fascinating to see not just what is different in substance or sample, due to the foreign perspective/different life experiences by such historical agents on the CW/WBTS, but what they had in common with those ‘born and bred’ in America, either North or South, re. it.

George Brown of Canada West, (now Ontario), made his landmark two speeches which, based on obvious, extensive research both in person and from credible information sources, validated both the ‘source of the conflict’ arguments of North and South…and blamed both just as much for both.

https://diplomacy.state.gov/u-s-diplomacy-stories/the-trent-affair-diplomacy-britain-and-the-american-civil-war/

The spectre of a war between the Union and the British Empire was by no means out of the question by the end of the war, as Abraham Lincoln himself mused!

The battleground would obviously have been Canada! See his words on pages 406-07

https://archive.org/details/campaigningwith00unkngoog/page/406/mode/2up?q=england

‘Campaigning With Grant’, by Horace Porter, pp 406-07

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, in his opening speech as Maine Governor, (perhaps rumbling in the veins of the Aroostook War between Maine and New Brunswick almost 30 years earlier), passed combative observations upon the coming-Confederation of Britain’s North American colonies that was to come in July of 1867-

“The Governor does not approve of the Canadian Confederation scheme, or of the idea of being “environed by monarchies”, as danger to the State would be the consequence.” 4 January 1867.

As cited in the 8 January 1867 ‘Maine Democrat’.

http://biddeford.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?t=34994&i=t&by=1867&bdd=1860&bm=1&bd=8&d=01081867-01081867&fn=maine_democrat_usa_maine_saco_18670108_english_2&df=1&dt=4

And I always liked this particular copy of the ‘Daily British Colonist’, 11 October 1861, colony of Vancouver Island.

See the poem on the far left column and the article that begins beneath it and goes into the next column.

https://archive.org/details/dailycolonist18611011uvic/mode/2up?view=theater