A Failure to Organize: Philadelphia’s Board of Trade Rifles

I’m a sucker for a good recruiting poster. Their patriotic images and garish text so often evoke the pomp, pageantry, and enthusiasm on display in the early years of the Civil War. These broadsides can tell us a lot about the time or region in which the recruiting was happening, often playing on the pride, financial exigencies, or even fears of the men they were targeting.

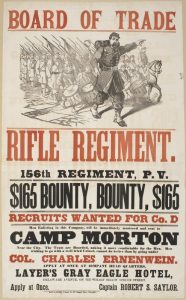

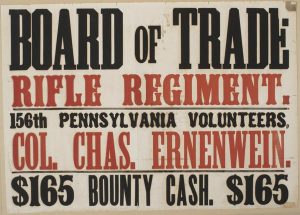

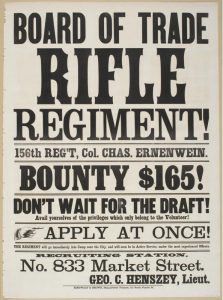

Recently, while searching Pennsylvania broadsides I came across a recruiting poster for a regiment I wasn’t familiar with. And then another for that same regiment. And then another. In all I found five different posters for this regiment. That’s an impressive number for any one regiment to have produced, let alone to have survived for 160 years. Recruiting posters were ephemeral in nature, not printed with the intention of outliving their period of immediate usefulness, which makes them so highly sought after by modern collectors and prized by museums.

When I started to dig into this regiment, I was surprised to find little information. They had no assignments, endured no hard marches, and experienced no horrors of the battlefield. In fact, they never left camp. This was a regiment that failed to organize.

Charles Ernenwein had been yearning to raise a regiment for service. Following an eight-year stint as an officer in the Bavarian army, he had been in this country for more than a decade, working as a milliner in Philadelphia. With the outbreak of civil war in his adopted country, he volunteered his services and was elected lieutenant colonel of the 21st Pennsylvania Infantry, an ethnically German regiment assigned to General Robert Patterson’s Department of Pennsylvania.

After his discharge in August 1861, Ernenwein began stumping for his own command. In October 1861 he called on President Lincoln for “a respectable place in the service.”[1] Such a place was not immediately forthcoming, and Ernenwein waited nearly a year for an opportunity. But following Lincoln’s July 1, 1862 call for an additional 300,000 volunteers, the need for experienced officers ensured Ernenwein would get his chance.

Ernenwein received permission to raise a regiment for a three-year term of service, designated as the 156th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Sponsored by Philadelphia’s engine of economic development, the regiment adopted the moniker of the Board of Trade Rifles. Ernenwein secured a campsite, dubbed “Camp Morton,” across the Schuylkill River on Islington Lane (modern day Kingessing Avenue) opposite the Odd Fellows Cemetery. Recruiting posters promised wood-floored tents, clothing, and rations to enlistees, and a “man of respectability and means” was advertised for regimental sutler to satisfy the men’s needs.[2]

Offering a $165.00 bounty, the regiment was billed as “well-officered” and sought “men of good character.”[3] One recruiting poster advertised the officers as “most experienced,” while another suggested that recruits “cannot do better” than a “well tried” colonel in Charles Ernenwein. How well-officered the regiment was is a matter of conjecture, as a search of those officers who we can identify demonstrates few with prior military experience. Indeed, by late October the regiment was soliciting “competent officers, with men” to help fill out the regiment.[4]

Despite reports that there was “no doubt of the early filling up the regiment,” recruiting floundered.[5] While the regimental headquarters were “brilliantly illuminated in all the windows” and the national colors “floated gaily over the front of the house,” after two months the regiment had enlisted only 254 men, barely enough to fill two companies.[6] It was nearly mid-December before the first full company was filled out.

By Christmas 1862 it was clear that the status quo was not working. The bounty was increased to $175, including $25.00 cash in hand on enlistment, another $50.00 when the company was full, followed by $25.00 when the regiment was filled, and $75.00 at the expiration of their three-year term of service.[7] The increase was not enough to offset the bounties offered by other regiments recruiting in Philadelphia at the same time, including a substantial $302.00 bounty offered by the 3rd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery.[8] By early 1862 the Board of Trade Rifles had increased their bounty to $315.00, including $215.00 cash in hand, but the effort was too little too late.

By February 1863 Ernenwein was losing control of his command. Recruitment had all but evaporated, and those men who had enlisted were absconding from Camp Morton. In late February two men of the regiment filed suit against Ernenwein, alleging that he was withholding money from recruits. The colonel in turn filed suit against the men claiming that he had indeed withheld funds, believing the men would have deserted had he paid them, and that the men were otherwise conspiring to injure his command.[9]

Any judgment in the case was seemingly irrelevant. On February 27, 1862, Ernenwein received word that recruitment for the 156th Pennsylvania was abandoned, and that all remaining recruits were to be transferred to the 157th Pennsylvania, another Philadelphia regiment struggling with recruiting.[10] Ernenwein’s remaining command was enough to fill just one company in the 157th, which was soon mustered into service at battalion strength with just four companies (dubbed the First Independent Battalion). Both Ernenwein and the colonel of the 157th, William A. Gray, were relieved of their duties. Gray later commanded the 52nd Pennsylvania Emergency Militia in the summer of 1863, while Ernenwein saw no further service. The men of the 157th went on to see hard fighting at Cold Harbor, Bethesda Church, and Petersburg, before being transferred to the 191st Pennsylvania Infantry.

The 156th and 157th Pennsylvania were not the only state regiments to struggle with enlistments. There were an additional five Pennsylvania infantry regiments (120th, 144th, 146th, 154th, 164th) that failed to organize from late 1862 through early 1863. Beyond the Keystone State, New York and Ohio combined for an additional seven failed infantry regiments during the same period.

What might have contributed to flagging recruiting during this period? Following the July 1, 1862, call for additional 300,000 troops, prospective enlistees needed only to open a newspaper to find casualty lists from the latest bloodlettings on the Virginia Peninsula, Second Bull Run, Antietam, and Fredericksburg, among a host of other battles. For many men, by late 1862 and early 1863, if you really wanted to be fighting in the Civil War and were of age and ability, you were probably already fighting in the Civil War.

In Pennsylvania and Ohio, vaunted Confederate armies had approached their very doorsteps, and even crossed into the states during lightning raids by J.E.B. Stuart and Albert Jenkins. Pennsylvania’s once appealing short-term militia enlistments – designated for service within the state – had instead seen their regiments removed to Maryland, within shouting distance of the Army of Northern Virginia.

What might have specifically contributed to the failed recruiting of the 156th Pennsylvania? Beyond the untried officers, the regiment also went out of its way to identify itself as the only three-year regiment then being recruited in the city of Philadelphia. While imploring men to enlist and avoid the draft, those same men could just have easily satisfied their obligation in any number of nine-month regiments being recruited in the city at the same time. In nearly doubling the bounty in hopes of enticing more recruits, the regiment only served to dishearten those men who had enlisted earlier for substantially less. With more than half of the earlier bounty coming only after the company and regiment had completed organization, the earliest enlistees accepted the realization that neither was likely to happen. Where the regiment had apparently numbered some 500 men in early October 1862, the number was halved by the beginning of November, and further reduced to approximately 100 men by late February 1863 as men continued to drift away from camp.[11]

The 156th Pennsylvania left no battle flags, no battlefield monuments, and no regimental history. They celebrated no regimental reunions, and you won’t find the regiment inscribed on any government headstone in your local cemetery. Their legacy is instead these five terrific recruiting posters that in their day didn’t quite work, but today serve to memorialize a regiment that failed to organize.

[1] Lincoln, Abraham. Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916: Abraham Lincoln, Saturday, Memorandum on Charles Ernenwein. 1861. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/mal1242700/>

[2] The Press [Philadelphia, PA], October 24, 1862

[3] ibid, October 01, 1862; October 24, 1862

[4] ibid, October 24, 1862

[5] ibid, December 10, 1862

[6] ibid, October 27, 1862; November 19, 1862

[7] ibid, December 25, 1862

[8] ibid, October 25, 1862

[9] ibid, February 28, 1863; March 3, 1863

[10] Bates, Samuel P. History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861 – 1865: Prepared in Compliance with Acts of the Legislature. Harrisburg, B. Singerly. 1869. Volume 8, Page 833

[11] The Press, October 1, 1862

thanks Jon-Erik for this neat article and great detective work …you’re right about why they had such a hard time filling the ranks — most guys of age who were willing to fight were already in the fight … and the shine of military service had clearly gone off the apple — many wounded back in the city, lots of neighbors and friends KIA, et al.

Thanks for reading, Mark!

What a wonderful article! If you find any Fire Zouave posters, let me know!!

Thanks Meggers!

Fascinating post, thanks. I’d be curious if Indiana and Illinois faced similar issues. Wisconsin did not; its only incomplete units came when the war ended as they were forming.

Thanks, CK! Illinois did not face similar issues, at least not during that period. Indiana failed to complete a number of regiments in the spring and summer of 1862, had another spate of failed infantry regiments over the fall and winter, and then a handful of others through 1863 and 1864. It would be interesting to contrast what circumstances led to these failures in each state. The proverbial rabbit hole…

Thanks for the post. I tend to forget the cumbersome, archaic ways the Union filled its ranks. I grew up during the Vietnam War drafts. Now we have a completely different, more professional approach. The post helps to reflect on the meaning, significance and effort associated with the short descriptions often attributed to officers who “raised” their regiments.