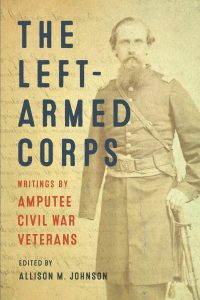

Book Review: The Left-Armed Corps

“I, without lamentation, bear a deep and lasting memento of the war for the Union in the loss of my right arm. … But thank God, our Country is saved.”– Private Henry L. Krahl, 13th US Infantry, October 27, 1865.[1]

“I, without lamentation, bear a deep and lasting memento of the war for the Union in the loss of my right arm. … But thank God, our Country is saved.”– Private Henry L. Krahl, 13th US Infantry, October 27, 1865.[1]

In the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War, chaplain and editor William Oland Bourne hosted two writing contests. In doing so, he collected over 300 pieces of writing or poetry from soldiers that had to learn to write left-handed after the loss of the ability to use their right arms through disabling wound or amputation. These writings not only showcased their re-learned penmanship, but also included accounts of their service, wounding, recovery, and mindset as they struggled in the postwar world of 1865-1867. In this volume, Allison M. Johnson, Assistant Professor of English at San José State University, has selected dozens of particularly poignant submissions, showing their lives and their struggles to the reader.

Rather than just listing out all the chosen entries, Johnson arranges them thematically into eight chapters. These include accounts of mustering in, soldier life, battle, medical treatment, poetry, and transitioning home to their changed lives. Entries are also introduced with a very brief biography of the soldier, and many excerpts even include photographs of the soldier, either from Bourne’s files or other repositories.

I’ll let one excerpt briefly speak for itself. Following an account of Yorktown during the Peninsula Campaign and his disabling injury when his cannon went off prematurely as his was loading it, shattering his right hand, Corporal Ezra Dayton Hilts of Battery D, 1st New York Volunteer Light Artillery wrote in November 1865 of the results of the war as he saw them:

“We are one people more than ever before. The wicked spirit which sought to sever the bonds of our Union and overthrow the government, served only to cement our Union more strongly, and to strengthen the whole framework of our government. The infamous system of slavery, which breeds rebels and assassins, has been torn up by the roots in our land as the greatest evil in Christian civilization, and the proud spirit of a slaveholding oligarchy, has, we hope, vanished from among us.”[2]

His submission continued with musings of what must be done in his present and the coming future to ensure the sacrifices he and his fellow soldiers made were honored and the unfinished work of reunion completed.

Johnson does an excellent job presenting extra information that enable readers and other historians to do their own research. The volume uses footnotes rather than endnotes, so the reference along with any explanatory text is found directly below the main text rather than the end, which I think works very well here. There is an appendix listing information on those who submitted to the contests, including name, residence, regiment, wound location, and contest entry number so readers can track down their complete entries. The index is very good at guiding towards soldiers writing about specific battles, specific units, or certain topics. My head spins with the research possibilities!

Though Bourne intended to publish a compiled volume of the submissions, he was never able to. Johnson admits this work does not contain every entry or each word submitted in selected passages since publishing every entry verbatim would take thousands of pages. Thankfully, a Library of Congress crowdsourcing initiative has worked to transcribe and review the original collection, and the previously mentioned appendix of submissions makes it very easy to hunt down the full text of an excerpt a reader found particularly interesting.[3] The availability of the complete sources at the public’s fingertips in no way diminishes the value of Johnson’s editing but instead enhances it.

Those interested in studying the ways Americans remembered their service will find that in abundance here; despite previous ideas that veterans “hibernated” until the 1880s, these pages note hundreds of veterans being very candid about their service and what the outcome of the war meant in 1865-1867. Many wholeheartedly praise the end of slavery and the coming of freedom for the formerly enslaved while being wary of reconciliation with their former foes. Readers interested in Civil War medicine or studying disability will certainly be drawn to the chapter compiling accounts of amputation and recovery, and those interested in battle accounts or the common soldier have plenty to read. Johnson’s well-written editorial comments in each chapter engage with the historiography of the various topics, and this volume is a must for those who are exploring a wide range of Civil War era topics.

The Left-Armed Corps: Writings by Amputee Civil War Veterans

Edited by Allison M. Johnson

Louisiana State University Press, May 2022

Reviewed by Jon Tracey

[1] Johnson, page 275.

[2] Ibid, page 79-82, 264-265, 340-341.

[3] The Library of Congress collection of William Oland Bourne Papers, including complete images and transcriptions of the submissions can be found at https://www.loc.gov/collections/wm-oland-bourne-papers/.

John Wesley Powell. Captain of Battery F, Second Illinois Light Artillery. While in command of his battery at Shiloh was struck by enemy fire and lost most of his right arm…

Those of us who study the Civil War concentrate on grand strategies and troop movements; we compare the best Northern generals to the best Southern generals; and we try to find lasting meaning and award noble value to the fighting of that greatest of American armed conflicts… but without confronting the shocking brutality endured by POWs of both sides; or getting too caught up in the struggle just to survive of newly widowed women and orphaned children; or thinking too long about war-crippled men forced to endure every day for the rest of their lives: missing limbs; displaying horrific facial injuries; struggling with ongoing “internal health issues…”

The ”writing contests” were an effort to give hope; and direct energy towards “appreciating what one has, instead of focusing on what one has not.”

In the case of John Wesley Powell, he employed self-motivation to avoid becoming a victim; engaged in Western USA explorations that even “unimpaired” people would find difficult. Commencing 1867 he led geological specimen collection expeditions through the Colorado Rockies. And beginning 1869 he conducted rafting explorations of the Grand Canyon. His efforts resulted in assignment as Director of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Thanks to Jon Tracey for bringing this resource to our attention.