Hispanic Americans in the Civil War

In honor of Hispanic Heritage Month (September 15 – October 15), I’d like to provide our ECW readers with an overview of the contribution that Hispanic Americans made to the Civil War. Across the nation, Americans and immigrants that could claim some lineage to Spain, Portugal, Cuba, Mexico, or any other Central and South American country, were impacted by the conflict between North and South. By the close of the war, over 20,000 Hispanic Americans would fight for their respective side.

Just like the soldiers from Alabama or Maine, Hispanic Americans had their own reasons for enlistment. Some, like the Creoles of Spanish heritage who lived along the Gulf Coast, were deeply invested in the preservation and expansion of the slavery institution. Those in the southwest, mainly California and New Mexico, retained their anti-slavery sentiments since Mexico, abolished slavery in 1829 – decades before the annexation of these states into the Union. Tejanos (Mexicans from Texas) were divided. While many were also firmly dependent upon slavery – since there was widespread support of the enslavement of local indigenous people – and sided with the Confederacy, others harbored mistrust of the rising aristocracy of white landowners and sided with the Union. Many did not consider the issue of slavery when they enlisted, but joined up for patriotic loyalty, such as the Hispanic immigrants who lived in the North. These immigrants, often a target of racial or nativist prejudice, saw their opportunity to prove themselves as true Americans by fighting in the war to preserve the Union. Still countless other Hispanics joined for more pragmatic reasons. They enlisted to financially support their families or joined militias to protect their homesteads. Their unique stories have long been overlooked by historians with only a small handful of books to cover their remarkable and fascinating impact on the war.

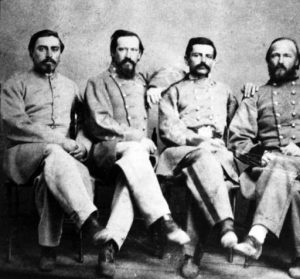

On the Confederate side, the “European Brigade” was composed of 4,500 volunteers that made up one of the home guard units in New Orleans. Of those 4,500, almost 800 were of Hispanic heritage. More Hispanic Louisianians served in the infamous brigade dubbed the “Louisiana Tigers” amongst other Creoles who fought at major engagements like Antietam and Gettysburg. The 55th Alabama and 2nd Florida Regiments also boasted large numbers of Hispanic Confederates from the Gulf Coast. Numerous blockade runners threw in their lot with the Confederacy, most notably Captain Michael Usina, who began his enlistment in the 8th Georgia Volunteer Infantry but after receiving a serious wound early in the war, joined the navy. He ran many successful missions, narrowly avoiding capture each time.

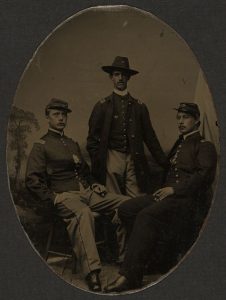

For the Union, the 39th New York Regiment, also called the “Garibaldi Guard,” boasted a wide sampling of European ancestry including Hungarians, Swiss, German, and French immigrants, but the regiment included a company wholly composed of Spanish and Portuguese soldiers. Their unique European-style uniforms made them stand out on the battlefield at Gettysburg, Mine Run, and the Overland Campaign. The 1st California Cavalry Battalion served in New Mexico and was comprised almost entirely of Mexican-Americans, twelve companies of which were raised in Texas. To function efficiently, officers needed to be fluent in Spanish. The Union Navy did not lack in Hispanic sailors. Two figures that stand prominently amongst their crews were John Ortega and Phillip Bazaar. Ortega served on the USS Saratoga and helped to enforce the blockade around Southern ports. One must wonder if he ever came across Captain Michael Usina. Bazaar sailed upon the USS Santiago de Cuba and fought alongside Ortega at the battle for Fort Fisher, North Carolina. He became one of only six men to breach the Confederate works and delivered crucial dispatches during the battle. Bazaar and Ortega both earned Medals of Honor for their bravery during the assault.

However, these two were not the only Hispanic soldiers awarded the Medal of Honor. Joseph H. De Castro was the flag-bearer for the 19th Massachusetts Infantry at Gettysburg. Along Cemetery Ridge during Pickett’s Charge on July 3rd, De Castro attacked the flag-bearer from a Confederate regiment. He captured the Confederate colors and promptly ran back through the lines to hand them to Colonel Arthur Devereux before returning to the fight. He became the first Hispanic American to be awarded the Medal of Honor for his valor on that day.

Others were not awarded, but their work is remembered. Henry Pleasants was born in Buenos Ares, Argentina, to an American father and Spanish mother. He immigrated to America at the age of 13 and became a mining engineer in Pennsylvania. During the war, he rose to the rank of second lieutenant in the 6th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, but he is most recognized for his involvement in a failed attempt to get inside the Confederate lines at Petersburg. While his ingenuity and initiative to devise a tunnel that would burrow underneath the enemy is admirable, the plan did not go quite as intended and resulted in the costly “Battle of the Crater.”

One Hispanic American largely succeeded in his duty and his part in the Union war effort cannot be overstated. Admiral David Farragut was the son of a Spanish captain and can therefore be considered Hispanic by lineage. His fame at New Orleans and Mobile Bay need little reiteration.

Luis F. Emilio, another son of a Spanish immigrant, lied about his age in order to enlist with the 23rd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. He was later chosen to serve as an officer in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, participating in the assault on Fort Wagner alongside black soldiers. He would be promoted to commander of the regiment after the failed assault and mustered out when he was not yet 21 years old.

Hispanic women also played their part in the war. Many were nurses, but a few stand out for their courageous actions. Lola Sanchez and her family were Confederate sympathizers residing along the St. Johns River in Florida. Lola, along with her sisters, acted as spies for Captain John Jackson Dickison, also called “The Swamp Fox of the Confederacy” and fed vital information to the captain regarding Union activity in their area. Loreta Janeta Velazquez followed her husband into the Confederate Army, disguising herself as a man and going by the false name of “Harry T. Buford.” She fought at the first battle of Manassas and at Fort Donelson before being discovered. Even after she was kicked out of the army, she continued work as a spy.

Her memoirs were – and still are – hotly contested as either fanciful fiction or a reliable primary source for an example of women soldiers during the war. Still countless other Hispanic women endured hardships at home, such as at Socorro, New Mexico where the town suffered from a failed harvest, raids by Confederate troops and attacks from Apache and Navajo tribes. The tale of the resilient civilians who endured the hard wartime years epitomizes the adversities experienced in many other towns who fell in the path of both Confederate and Union armies.

These are just a few of their stories. Many more lie hidden in archives or family oral traditions. This September and October, I challenge our readers to consider the history of minority and ethnic groups that you may not have considered when thinking about the Civil War. The war impacted all Americans, white, black, and brown, from all walks of life and heritage, and their contributions are just as valid and worthy of research than any other.

For a great dive into other Hispanics in the Civil War, see this guest post by Carlos Mutis

Resources:

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/hispanic-americans-civil-war

https://www.nps.gov/stri/learn/historyculture/upload/Hispanics-in-Civil-War-8×8-booklet-lowres.pdf

https://www.thenmusa.org/articles/hispanic-americans-in-the-civil-war/

Books for further reading:

Tejanos in Gray: Civil War Letters of Captains Joseph Rafael de la Garza and Manuel Yturri, Jerry Thompson

Vaqueros in Blue and Gray, Jerry Thompson

thanks for remembering these great Americans … Hispanics continue their long legacy of service to the nation … and lets not forget Neil C’s recent essay on Manuel Moreno, the lighthouse keeper who shifted colors from CSA to USA during the war.

This is where it gets definitionally complex with evolving language and the language of places. In Louisiana Moreno would be considered Creole and not necessarily Hispanic. Broadly speaking today he is Hispanic, but in his day he would have thought himself as Spanish or Creole, I think. Dr. Chatelain might know precisely what Moreno thought he was.

So I have been trying to find Moreno’s heritage specifically, but so far have no answers regarding his cultural heritage or family origins. The name certainly sounds Hispanic and the Louisiana area definitely hints at some sort of Hispano-Creole heritage, but no documents have been found (yet!) to confirm. I need to get my hands on some earlier census documents to see where Moreno’s parents may have originated from. Spain did own Louisiana for 40 years after all.

A good friend in South Louisiana was named Acosta, but he was completely Cajun. I expect sometime in the past his family was from Spain and settled in Louisiana, but who knows.

Tom

If he’s Cajun then his ancestry would be from the Acadians, French Canadians who escaped to Louisiana as refugees after they were kicked out by the English in the 1700s. That’s the original definition of “Cajun,” but now it’s more of a cultural label to describe anything that resembles “backwoods/swamp people Louisiana.” The term “Creoles” defines as anyone who has direct ancestry from Spain, France, Caribbean, etc. There’s also Atlantic Creoles when discussing Africans who either had mixed parentage of Portuguese, French, Spanish, etc., or were purely African but participated in European culture for economic or pragmatic purposes. The words certainly have different meanings within different contexts and is a study all to itself.

good point … the term hispanic (derived from the word Hispania meaning of the Iberian Peninsula) is a word we have resurrected to categorize people … Moreno and other 19th century actors in Sheritta’s article might wonder why we do that.

If we define Hispanic to mean anything related to Spain, we must give a shout out to George G. Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, who was born in Cadiz, Spain. Vamos Meade!

In my own mind I see Hispanic as limited to Spanish speaking Latin-American peoples and countries, which would exclude the likes of Meade and maybe Farragut, but who am I.

There were some Cubano Confederates I know that served along the lower Atlantic. Connected to the antebellum Filibuster movement, I think.

Excellent post Sheritta. For more on the diverse ethnic groups and recent immigrants who fought in the Civil War see Pat Young’s excellent archived blog series on immigrants in the ACW.

I would add Santos Benavides, the highest ranking Mexican-Americanto serve in the Confedracy. He served as Colonel of the 33rd Texas Cavalry, which served along the Rio Grande. He was descended from the founder of Laredo, Texas – his uncle was Alcalde of Texas. He served as mayor of Laredo himself before the war. He successfully defended Laredo from invasion by Yankee forces in 1864.

Tom

We could also add the Tejanos who served in Hood’s Texas Brigade, such as Antonio Bustillos and Eugenio Navarro and Manuel Yturri who rose to Captain.

Tom

Great post, and thanks for shining a light on this topic. I’d add in Julius P. Garesche, who had Cuban roots and was killed at Stones River while serving as Rosecrans’s chief of staff.

There is information of hispanics who fought in both sides of the Civil War. But, it has been frustrating for me so far is that I still have not found the first one from my own country, Venezuela, different from the revolutionary war, in which some venezuelans fought serving in the Spanish Army and Navy that participated helping the patriots.

i can’t help with identifying any of your countrymen in the Civil War … but Venezula does have a namesake from the Cold War — USS SIMON BOLIVAR (SSBN 641) … a fleet ballistic missile submarine which served from 1965 to 1995.

Thank you Mark. I know the story of that ship. It was quite popular to name Bolivar to those kids born in the 1820s when the popularity of Simón Bolívar was in the top moment. Confederate General Simon Bolivar Buckner Sr., who surrendered to Grant at Fort Donelson, was named after him. Union General Orlando Bolivar Wilcox, also graduated at West Point. I also found some other soldiers named Bolivar who fought in the Civil War. There was a batte in the Civil War, the battle of Bolivar Heights in Virginia. Andrew Jackson named Bolivar his best and favorite racing horse. Simón Bolívar sent his nephew Fernando Bolívar to the United States with the intention of studying at West Point in the late 1820s. In the end, he did not. He started studying at the Unversity of Virginia but only did it for only one year because his bank was broke and came back to Venezuela.