Civil War Medicine: Andrew Henderson, John Pope, and a Challenging Medical Decision at Sea

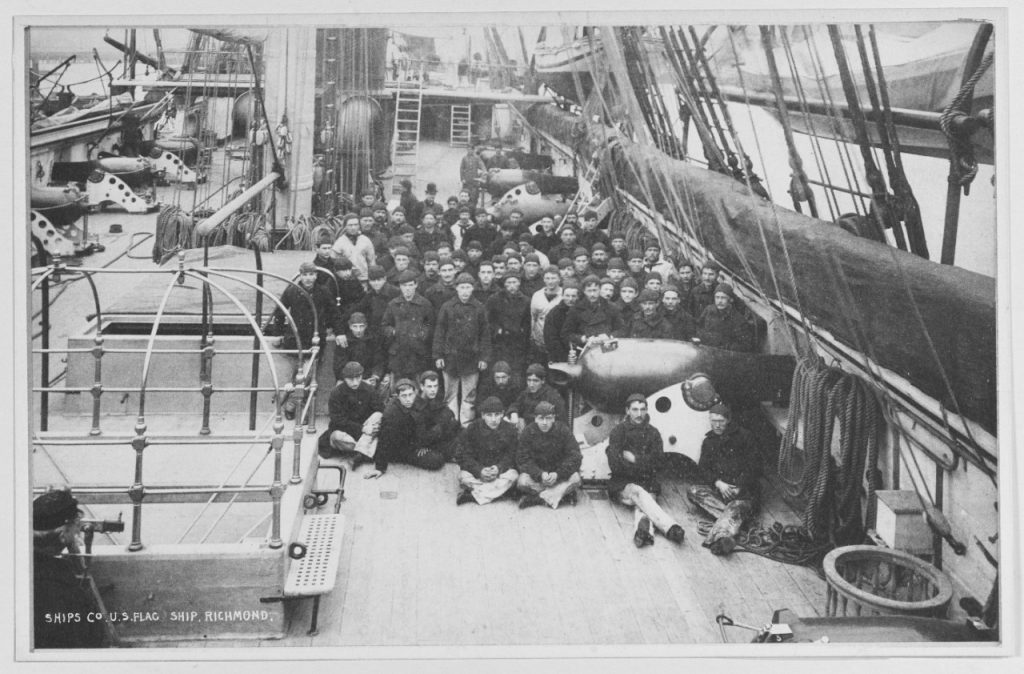

Civil War era warships were cramped with little privacy with sailors still sleeping in hammocks instead of beds. Officers generally had better living conditions, with the tradeoff of separation from the enlisted crew in status, activity, and expectations. Though they may have a cabin to call their own, officers generally felt more isolated. After all, a warship might only have two or three junior line officers, a couple of staff officers in supporting roles, and the vessel’s captain. This created quite the conundrum when it came to medical care. Warships generally had a medical officer assigned as ship’s surgeon, but that might be the loneliest billet of them all.

Civil War era warships were cramped with little privacy with sailors still sleeping in hammocks instead of beds. Officers generally had better living conditions, with the tradeoff of separation from the enlisted crew in status, activity, and expectations. Though they may have a cabin to call their own, officers generally felt more isolated. After all, a warship might only have two or three junior line officers, a couple of staff officers in supporting roles, and the vessel’s captain. This created quite the conundrum when it came to medical care. Warships generally had a medical officer assigned as ship’s surgeon, but that might be the loneliest billet of them all.

A naval surgeon was generally well educated, but they were not part of the chain of command regarding combat operations. They would never command a ship, instead focusing their time on keeping the crew healthy, caring for the sick, and treating casualties. As the ship’s sole medical expert, the proverbial buck stopped with them. Often there was no one else to call on regarding questions of treating a patient. Sometimes vessels in close proximity could transfer surgeons temporarily, but generally naval surgeons had a more imposing task than their army counterparts who could draw on supplies and staff at nearby hospitals or get assistance from the surgeon of a nearby regiment for a particularly tricky situation. The case of Captain John Pope and Surgeon Andrew A. Henderson highlights just how naval surgeons could be called on to make tough calls with little support that could significantly affect operations, while simultaneously examining the mental strain of command and defeat.

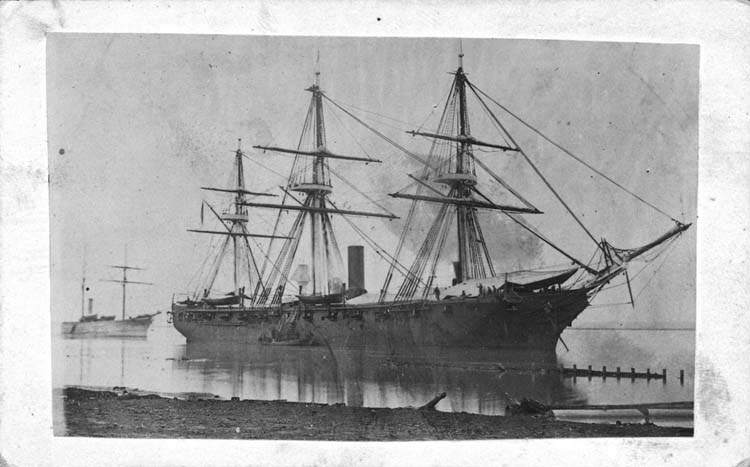

Yes, I said John Pope! But not Major General John Pope of the battle of Second Bull Run. There was in fact another John Pope in the United States Navy. This John Pope held the naval rank of captain in 1861, equivalent to an army colonel, and commanded USS Richmond, a steam sloop-of-war mounting 22 heavy cannon, mostly all 9-inch Dahlgren shell guns.

USS Richmond was a new ship, only commissioned in 1860. Pope was given command of the vessel while in Europe in March 1861 after its captain resigned to join the Confederacy mid-cruise.[1] It was then recalled home. Returning to US waters, Richmond unsuccessfully hunted the Confederate commerce raider Sumter before joining the Gulf Blockading Squadron.

Being a very senior officer, Pope was assigned by Gulf Blockading Squadron commander William McKean to oversee the Mississippi River delta’s blockade. In late September, Pope led several ships into the Head of Passes, where the several channels of the Mississippi’s delta converged. Occupying this position meant the ships could block all river traffic more efficiently than blockading each individual pass.

Confederate naval forces launched a surprise attack on the US blockade at the Head of Passes on the early morning of October 12, 1861. Captain Pope’s ships retreated, but USS Richmond and USS Vincennes ran aground on the Southwest Pass bar where Confederate ships fired on them for several hours. In the chaos, Vincennes’ captain ordered his ship abandoned, supposedly from a signal sent by Pope, which only compounded Pope’s woes that day.

The embarrassing defeat at the Head of Passes was only the beginning of troubles for Pope, a man born in 1798 with 45 years of naval service! He spent the night of October 12 worried about continued Confederate attacks, keeping his sailors on continuous guard. The pair of ships were painstakingly refloated off the channel bar the next day, but USS Vincennes had to toss overboard most of its cannon to lighten the ship enough. Hearing of the defeat, Pope’s boss, Captain McKean, reached Southwest Pass on October 16 to ensure the blockade was maintained, investigate the defeat, and determine if a court of inquiry was warranted.

Officers across the US Navy were aghast at the defeat. Another Gulf blockade officer, Surgeon Joseph Shively, called Pope and the other captains involved “base cowards.”[2] Captain Hiram Paulding called the battle “a sad story.”[3] Then-Lieutenant David Dixon Porter called it “the most ridiculous affair that ever took place in the American Navy.”[4] One of Richmond’s junior officers, Acting Master Frederic Hill, called the battle “our comedy of errors.” It was quickly labelled “Pope’s Run.”[5]

The pressures of command, defeat, embarrassment, and constantly guarding against another surprise attack strained Captain Pope to the breaking point. Unable to handle it, within days Pope approached USS Richmond’s surgeon, Andrew A. Henderson, asking him to declare Pope unfit for command (or if you want to think more into the issue of honor and command relationships in the naval service, Henderson very well may have approached Pope with an ultimatum of either asking for a medical review or having one convened regardless).

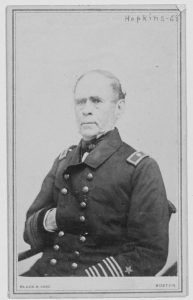

Besides serving in the US-Mexican War Henderson was an almost stereotypical 19th century naval surgeon who collected specimens of flora and birds wherever he sailed, like Charles Darwin or the character Stephen Maturin in Patrick O’Brian’s novels. He conducted a full medical examination of Captain Pope on October 15, three days after the surprise attack.

Henderson sent a letter to Gulf Squadron Commander William McKean dated October 22 detailing the examination’s results. He explained Captain Pope had a “slow and weak pulse” and “had vertigo,” “could sleep but little,” and “had no appetite.” More alarmingly Henderson noted Pope had “inertness of mind” and was “suffering from nervous exhaustion,” causing “mental anxiety and loss of sleep.” He did not expressly state it, but it seems Henderson believed Pope was suffering from post-traumatic stress enflamed by the surprise attack and retreat from the Head of Passes. This only compounded an “affection of the liver” that began years before in an antebellum cruise near China.[6]

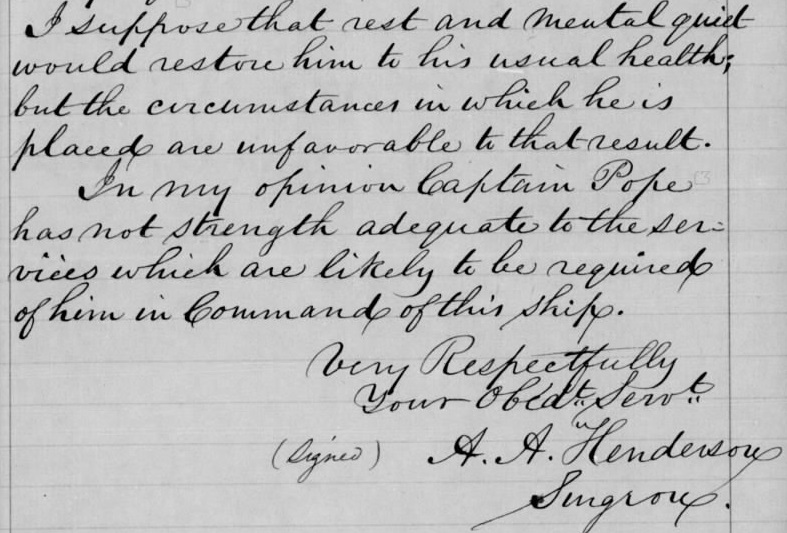

As far as recommendations, Surgeon Henderson began treating Pope “with an opiate.” He went further, recommending “rest and mental quiet” before officially declaring “Captain Pope has not strength adequate to the services which are likely to be required of him in command of this ship.”[7] In forwarding the report, Captain Pope agreed with the surgeon’s findings and officially asked “to be relieved from the command of the Richmond and return home,” though he blamed the need on his liver issues, not combat-induced post-traumatic stress.[8] Captain McKean agreed with Henderson’s report and Pope’s request, ordering him “detached … from the command.”[9] Pope was retired from the Navy in 1862, never attaining another command.

In this instance Surgeon Andrew Henderson was left to make the tough call alone. With such pressures, and with the career of one of the Navy’s most senior officers at stake, he ultimately recommended Pope’s relief. Based on the medical report, it very well could have saved Pope’s life and avoided a complete mental breakdown.

It took a lot for a Civil War officer to be declared medically unfit for command. Over the course of the conflict very few were (think how General John B. Hood was never medically discharged even in late 1864), making Pope’s October 1861 relief all the more significant considering the major issue concerned the captain’s mental health. Perhaps the fact that Henderson was the only medical officer available helped him make a decision that was unlikely to be countered by a more senior medical officer. Perhaps he made the call because he did not trust Pope to command the very ship he was assigned to in another battle. Perhaps he was just looking out for a friend and fellow officer, trying to protect him from future investigations. No matter the reason Henderson was alone in recommending Pope’s medical relief, highlighting how naval surgeons were often left to act alone in making tough calls or in caring for the sick and wounded. It is surprising that more naval surgeons in Henderson’s position did not crack under such pressure themselves.

Endnotes:

[1] March 19, 1861, Journal of a cruise in the U.S. Steam Sloop Richmond, MSS 097, Item 041, University of Delaware Library, http://udspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/11175.

[2] October 31, 1861, Journal of Surgeon Joseph Warren Shively, Spared & Shared, https://sparedshared22.wordpress.com/2021/10/11/the-civil-war-journal-of-dr-joseph-warren-shively/, Accessed June 3, 2022.

[3] Paulding to Fox, October 23, 1861, Robert Means Thompson and Richard Wainwright, eds., Confidential Correspondence of Gustavus Vasa Fox, Vol. 1, (New York: De Vinne Press, 1918), 387.

[4] David D. Porter, The Naval History of the Civil War, (New York: Sherman Publishing Company, 1886), 91.

[5] Frederic Stanhope Hill, Twenty Years at Sea, (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, & Company, 1893), 160-161.

[6] Henderson to McKean, October 22, 1861, Gulf Squadron, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Commanding Officers of Squadrons, M89, RG 45, US National Archives.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Pope to McKean, October 22, 1861, Gulf Squadron, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Commanding Officers of Squadrons.

[9] McKean to Welles, October 24, 1861, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Ser. 1, Vol. 16, 748.

Great post Neil. Thanks. It should be noted that the term “surgeon” did not imply medical degrees and operating room expertise as now understood. He also was called the ship’s doctor, a general practitioner in charge of crew health. Education was more apprenticeship and experience than formal education. He was certified by a board of surgeons and ranked as a warrant officer.

Good clarification Dwight. Surgeon (or assistant surgeon, or passed assistant surgeon) were ranks held in the naval service in the Civil War Era. They did not specifically mean someone was a qualified actual surgeon. Instead it simply denoted the position of the crew member, just as a petty officer who handled sails or cannon had specific titles as well.

Neil P. Chatelain

Thanks for this informative report bringing to light “the rest of the story” behind the US Navy action at Head of Passes. In my study of Civil War operations on Pensacola Bay the assignment of Captain Francis B. Ellison to command of the USS Richmond was asserted without explanation of what happened to Captain Pope. USS Richmond was instrumental in the reduction of Confederate Fort McRee on Pensacola Bay in November 1861.

Cheers

Mike Maxwell