How was President’s Day Celebrated During the Civil War?

Happy President’s Day! Hopefully you’re fortunate enough to have today off as you read this. And you may be wondering, how was this holiday, which celebrates the United States federal government’s chief executive, celebrated in the midst of the Civil War?

For one thing, it wasn’t called President’s Day until the late 20th century. In the mid-1800’s, it was celebrated as Washington’s Birthday, and fell on February 22 each year. In the words of Private Ferdinand Ickis of Dodd’s Company of Colorado Volunteers, Washington’s Birthday was observed as a day of “great rejoicing.” [1]

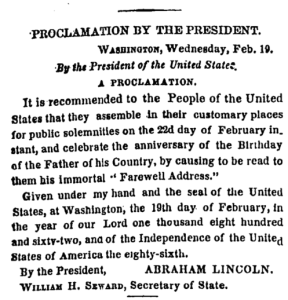

Ickis was in the New Mexico Territory’s Fort Craig on February 22, 1862, too far west to know that three days earlier, President Lincoln had issued a proclamation calling for the day to be celebrated nationwide with the reading of Washington’s Farewell Address. [2]

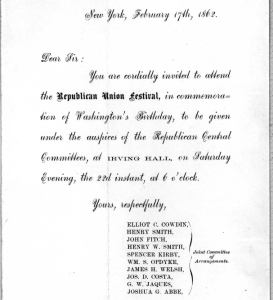

In accordance with Lincoln’s proclamation, New York City’s Mayor George Opdyke called for “a general suspension of business,” and the New York Times announced a wide variety of parades to be held, salutes to be fired, and similar gatherings. General Winfield Scott attended a “mass meeting of the citizens” at the Cooper Institute, and Washington’s Farewell Address was read at church services and parties across the city. City Hall was lit up to celebrate the occasion, reportedly at the mayor’s personal expense. [3][4]

At least in New York City, these celebrations would grow considerably as the war went on. By 1864, Mayor C. Godfrey Gunther, successor to Mayor Opdyke, protested the expense by declining to participate. Instead, he chastised the City Council for spending “thousands of dollars of the people’s money on such occasions, for what can scarcely be considered less than selfish indulgences.” With a delightfully modern tone, the 1864 New York Times described Opdyke’s as having “spicy views” on the matter. [5]

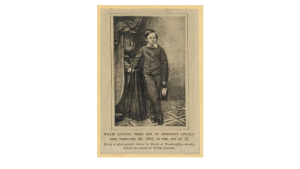

Official celebrations in the nation’s capital were somewhat more muted than in New York City. The day after issuing his proclamation, President Lincoln lost his son Willie to typhoid fever. It was a tragedy that the Lincolns would struggle with for the remainder of the war. As a result, “it was resolved that the illumination of the public buildings in Washington should not take place to-night, as previously arranged. [6]

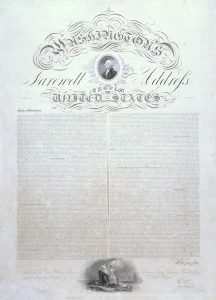

A joint session of Congress still commemorated the occasion by reading Washington’s Farewell Address, hoping to invoke the memory of the nation’s previous formative war. [7] That tradition continued intermittently through the remainder of the 19th century, and has since become an annual occurrence, conducted by a member of alternating parties. This year, Senator James Lankford (R-OK) is reading the Address; last year Senator Patrick Leahy (D-VT) read it. [8]

The address is most frequently referenced today for imploring the country to avoid factionalism in the form of political parties, and to beware the foreign entanglements and alliances that had, in Washington’s view, led to centuries of warfare in Europe. But Washington also spends considerable time imploring his audience not to take the benefits of the Union for granted. Anticipating how easily the new country could come apart at the seams, Washington said:

“The unity of Government, which constitutes you one people, is also now dear to you. It is justly so; for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquillity at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very Liberty, which you so highly prize. But as it is easy to foresee, that, from different causes and from different quarters, much pains will be taken, many artifices employed, to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth; as this is the point in your political fortress against which the batteries of internal and external enemies will be most constantly and actively (though often covertly and insidiously) directed, it is of infinite moment, that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national Union to your collective and individual happiness; that you should cherish a cordial, habitual, and immovable attachment to it; accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it as of the Palladium of your political safety and prosperity; watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion, that it can in any event be abandoned; and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.”

Lincoln didn’t choose to invoke Washington’s memory merely for some speeches and parties. He also issued General War Order #1, which called for a concerted move forward by all of the Union’s armies in the field. Historians have questioned the wisdom of this order, which resulted in little if any forward movement by Union armies. Their most significant victory that month was at Fort Donelson, which Grant had been clamoring to attack since well before Lincoln’s order.

In concept, though, it’s one of the first threads we see of an emerging approach to the war that Lincoln and Grant would gradually hone in on over the next two years, to leverage the North’s manpower advantage with simultaneous offensives across theaters of the war.

South of the Potomac, Jefferson Davis clearly took a different meaning from Washington’s Farewell Address. On February 22, 1862, he was sworn in to his full term as the first President of the Confederacy; previously, he had been acting in an interim capacity. In his inaugural address, he made clear that the symbolism of the day hadn’t escaped him, opening by noting that:

“On this the birthday of the man most identified with the establishment of American independence, and beneath the monument erected to commemorate his heroic virtues and those of his compatriots, we have assembled to usher into existence the Permanent Government of the Confederate States.” [9]

The issue of the Richmond Examiner that printed Davis’s speech devoted far less space to the inauguration than it did to reporting on the disaster that had befallen Confederate forces at Fort Donelson, though the full scale of that hadn’t yet become apparent to them.

Circling back to Private Ickis in the New Mexico Territory, who had called Washington’s Birthday an occasion for “great rejoicing” throughout the country, I think that his recounting of the day is more representative of the typical wartime experience than all of the speeches and parties in New York, Washington and Richmond. Ickis spent an especially grim February 22, 1862, climbing through piles of corpses. He was, desperately trying to identify the friends and comrades who had died in the previous day’s Union defeat at the battle of Valverde, the largest battle of Confederate Brig. Gen. Sibley’s invasion of the New Mexico Territory.

In his diary that day, Ickis wrote, “I have been in the room where the dead are piled up looking for one of our boys who is missing – Harrison Berry but did not find him…Never did I expect to go into a room where there were fifty men piled one upon another climb over them rolling them over seeking for a friend and this too without a shudder. Who will say war is not degrading.” [10]

[1] Mumey, Nolie. Bloody Trails Along the Rio Grande: A Day-by-day Diary of Alonzo Ferdinand Ickis. The Old West Publishing Company. 1958. 81-82.

It’s also worth noting that Washington wasn’t exactly born on February 22. He was born on February 11, 1731, while the British Empire still used the Julian Calendar. When the Empire switched to the Gregorian Calendar in 1752, Washington’s birthday became February 22, 1732. You can read more about this at the National Archives, or listen to the Julian Calendar episode of the excellent podcast This Day in Esoteric Political History.

[2] “Proclamation by the President,” The New York Times, February 20, 1862.

[3] “Washington’s Birthday in New York,” The New York Times, February 21, 1862.

[4] “The Celebration Today,” The New York Times, February 22, 1862.

[5] “Municipal Banquets; Spicy Views of the Mayor Thereon,” The New York Times, February 20, 1864.

[6] “News of the Day,” The New York Times, February 22, 1862.

[7] “Washington’s Birthday: The Order of Ceremonies to be Observed at the National Capital,” The New York Times, February 21, 1862.

[8] “About Traditions & Symbols | Washington’s Farewell Address,” United States Senate.

Thank you to Daniel Holt, Assistant Historian at the U.S. Senate Historical Office for providing information regarding this year’s reading.

[9] “Inaugural Address of President Jefferson Davis of the Confederate States; Delivered February 22, 1862,” Richmond Enquirer, February 25, 1862.

[10] Mumey, Nolie. Bloody Trails Along the Rio Grande: A Day-by-day Diary of Alonzo Ferdinand Ickis. The Old West Publishing Company. 1958. 81-82.