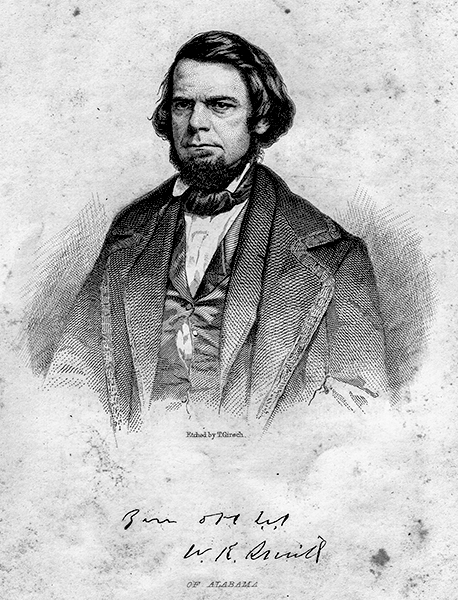

Mourning the Dead Union: William R. Smith and the Alabama Secession Convention

William R. Smith wrote his wife on January 12, 1861, the day after Alabama’s state convention passed an ordinance of secession. “The sternest men have been weeping like little children,” he moaned. “I have seen Mr. Jemison crying!” [i]

Smith and Robert Jemison, Jr. were the most outspoken Unionist delegates at the Montgomery conclave. In the defining hours of the sectional crisis that led to disunion and ultimately civil war, Southern Union men faced a wrenching moral dilemma. Allegiances to God, family, state, and nation that seemed simple in antebellum America became a tortured mental calculus, pitting cherished loyalties against one another. The very definition of “loyalty” itself became fluid and situational, inexact and ambiguous. [ii]

When faced with the most momentous choice of their public lives, Southern Union men did not weigh the benefits and dangers of dissolving the Constitutional compact using only logical deliberation. They struggled mightily with a complex range of conflicting emotions that were instrumental in their decision-making process. This intersection between private feelings and public allegiance deserves more attention from historians and social psychologists studying loyalty. [iii]

Born in Kentucky in 1815, Smith lost both parents in childhood and was raised in a foster home in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. A local attorney recognized his intellectual gifts and sponsored him in the first class of students when the University of Alabama opened in 1831. At just eighteen, he published the state’s first book of poetry written by an Alabamian. Following his establishment of the state’s first literary magazine and a career in law and newspapers, he began a meteoric rise in politics as a Whig state legislator and a Democrat, Independent, and Know-Nothing during three terms in the U.S. Congress. [iv]

Smith often crossed rhetorical swords with William L. Yancey, Alabama’s leading fire-eater. Yancey and his allies in the state legislature leveraged the emotional impact of the Harpers Ferry raid. In February 1860, the Alabama legislature passed a resolution calling for a secession convention in the event of a Republican candidate victory in the upcoming presidential election. Yancey stoked fears of “another John Brown raid,” suggesting that a Republican administration would not protect citizens from “men prowling about through the whole country.” His ability to rouse audiences into an emotional frenzy earned him the sobriquet, “Orator of Secession.” [v]

The one hundred elected delegates who gathered in the state capitol’s house chamber on January 7, 1861, divided themselves into three factions. Radicals called for immediate secession by independent state action, following South Carolina’s lead. Cooperationists favored secession, but via a unified effort of slaveholding states. A sizable minority, led by Smith and Jemison, argued that the crisis should be resolved within the Union. [vi]

Smith was under no illusion that Union men would carry the convention and despaired of the consequences. “The people will be overwhelmed with troubles,” he wrote to his wife on the eve of the critical vote, “but there will be a day of reckoning for the wicked.” From the outset of the proceedings, convention leaders struggled to control the emotionally charged atmosphere and promote calm, respectful debate. [vii]

The first resolution, proposed by George C. Whatley, was designed to “ascertain the sense of this body upon the question of submission or resistance to Lincoln’s Administration.” Smith immediately rose to object to the measure as a thinly veiled loyalty test. “We scorn the prospective Black Republican rule as much as the gentleman from Calhoun,” he assured his colleagues, but if the secessionist majority persisted in creating suspicion and internal enemies, they would have nothing but “the most unpleasant scenes of stubborn, sullen, and unyielding antagonism.” [viii]

Yancey responded defiantly, admitting that the resolution was a test and that “the world shall know” who was willing to defy the so-called “Black Republicans.” Former senator Jerimiah Clemens of Madison County assured Yancey that although Unionists might be persuaded to denounce Lincoln, “we cannot be driven one inch in any direction, and the attempt to do it will not only result in failure but must produce a state of things whose consequences I will not picture.” In the interests of harmony and cooperation, the resolution was amended to simply state that Alabama would not submit to the Lincoln administration upon the principles stated in the Constitution. It passed unanimously, ending the first day’s deliberations but not the emotional tension that filled the chamber. [ix]

The second day of the convention opened with Yancey inviting South Carolina’s Andrew Pickens Calhoun, son of the famous orator, to address the delegates. Applause in the galleries proved so disruptive that convention president William M. Brooks suggested that the galleries be cleared. Jemison then proposed secret sessions, which were adopted. [x]

Excitement built in succeeding days as telegrams from other Southern state conventions routinely interrupted proceedings, “no doubt most of them false,” Smith penned his wife, “calculated and intended to mislead and hasten the action of the convention.” Florida asked Alabama to send five hundred troops to the border at Pensacola immediately to defend against potential Federal aggression. Smith argued that such hasty action would constitute an act of war and treason, but the measure passed. The next day, Smith opposed a resolution to aid seceding states in the event of “coercion” by the U.S., prompting Yancey to describe Smith’s speech as “sneeringly” delivered. [xi]

In a vehement thirty-minute oration later published in the Montgomery Mail, Yancey warned Smith and other Unionists to fall in line or become “enemies of the State,” and traitors. “The misguided, deluded, wicked men in our midst, if any such be, will be in alignment with the abolition power of the Federal Government, and as our safety demands, must be looked upon and dealt with as public enemies.” The convention erupted in excitement. Smith privately disclosed “a calm and deliberate determination here to hold our enemies accountable in the future before the people whose will has been violated – and whose peace, if not liberty, has been destroyed.” [xii]

Jemison was offended and incensed by Yancey’s remarks. “Will the gentleman go into those sections of the State and hang all who are opposed to secession? Will he hang them by families, by neighborhoods, by towns, by counties, by Congressional districts? Who, sir, will give the bloody order? Who will be your executioner?” Delegates from northern Alabama, whose constituencies were largely opposed to secession, argued for the question to be referred to the people in a popular referendum, where they were confident that disunion would fail. [xiii]

Meanwhile, Mississippi and Florida passed secession ordinances by overwhelming margins on January 9 and 10 respectively, prompting Alabama delegates to call the question on January 11. “The speeches on this occasion were uttered in husky tones,” Smith reported in his published recap of the convention, “and in the midst of emotions that could not be suppressed, and which, indeed, there was no effort to disguise.” Smith voted against secession and refused to sign the ordinance, which passed 61 to 39, the narrowest margin in any Deep South state. [xiv]

As a public man and a representative, Smith had pledged to oppose secession and use all means to resolve the slavery question within the Union. But ultimately, he owed his primary political allegiance to his state. “You can’t imagine the delicacy of my position,” Smith explained to his wife, herself an ardent Unionist. “The act of secession having been consummated by a prejudging and unrelenting majority left me two alternatives – either to array the people of the state, one against the other, in a desperate civil war, or to surrender my scruples for the sake of union amongst ourselves. The latter course was prompted by every feeling of patriotism – by every sense of good judgment. I must share the state’s destiny.” In his heart, however, Smith remained troubled. [xv]

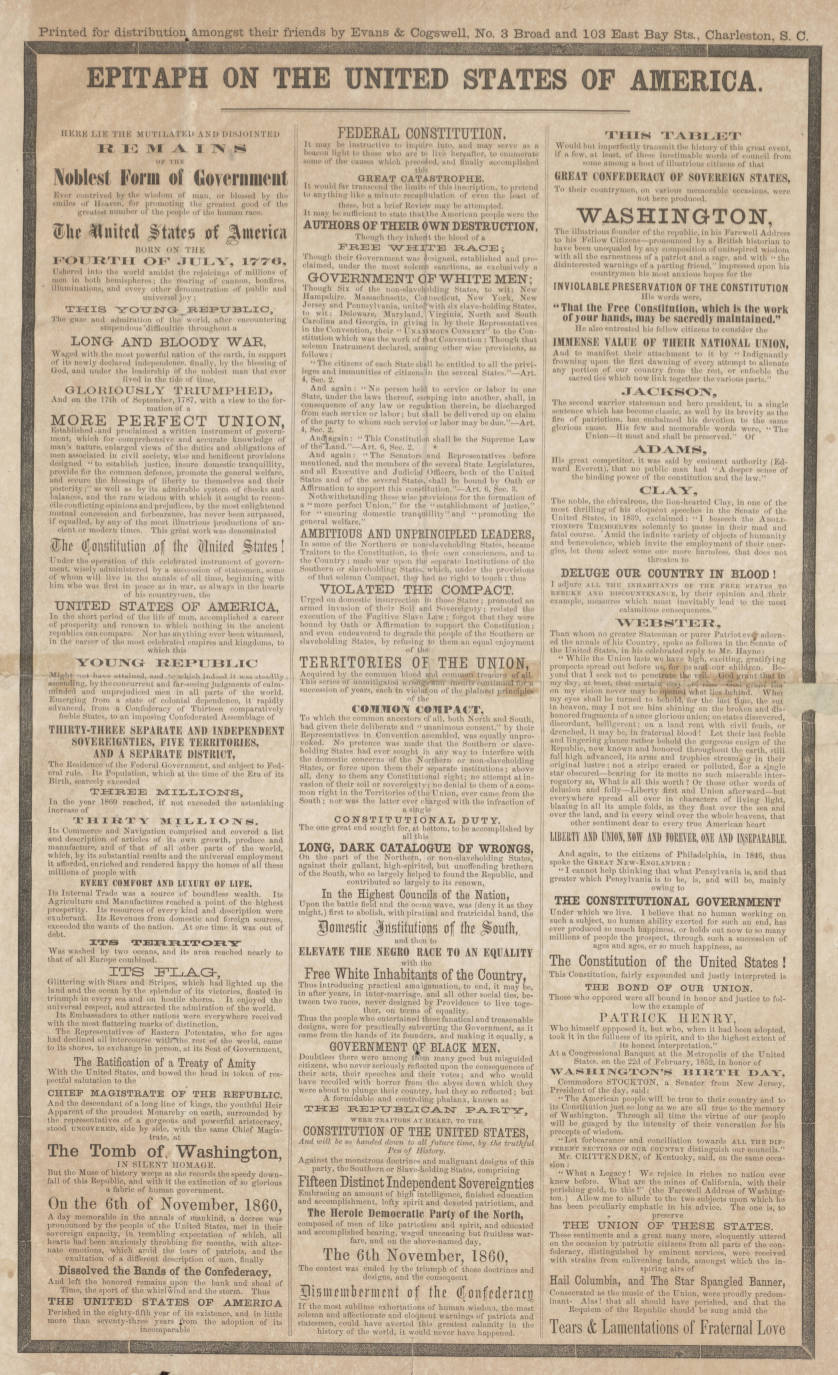

“They say in Revolutions there is no Sunday,” Smith wrote his wife on January 12. “God made a world and rested on Sunday. Man destroys a nation and works on Sunday.” Five days later, Smith begged for divine intervention. “The great event has happened and the gloomy day is gone. I cannot describe the oppression I have felt. I am a little relieved, as the excitement subsides. But the shadowy feeling in me wills the demons of dissolution. The country is destroyed unless God in his wisdom should roll back the tide of this disastrous Revolution.” To deal with the loss of their beloved country, many Southern men expressed their feelings in public mourning rituals. [xvi]

“Sir, I have loved, honored, and revered the Union of our fathers,” delegate James S. Clark lamented. “These recollections will be treasured up in the hearts of our countrymen as the sacred mementos of a dead friend.” When the ladies of Montgomery presented a huge flag to the convention president, Smith admitted that the scene “overwhelms me with emotions.” He vented his feelings in a funeral oration for the Star-Spangled Banner, “a flag sacred to memory, embalmed in Southern song…and consecrated in history…In parting, shall we not salute it?” As Alabama lowered the U.S. flag, Smith implored his audience, “Let he who has tears to shed, shed them now.” [xvii]

Smith did his duty to his state and his constituents while still trying to avert permanent separation and war. On January 22, 1861, he delivered a speech proclaiming the doctrine of Reconstruction and restoration of the Union. On April 13, he spoke for an hour against ratification of the new state constitution by the legislature and in favor of a popular referendum. Despite briefly commanding a rebel regiment and serving two terms in the Confederate House of Representatives, Smith remained ambivalent about his course and gloomy about the future. In early 1863, Smith joined 24 other members of the Confederate Congress proposing a peace resolution. He mourned the “destruction of the institutions which our fathers founded” and their replacement with war-like despotism on both sides. [xviii]

It is difficult to measure the cumulative effect of strong private emotions like betrayal, resentment, and indignation that coalesced over time into group norms and moral judgments. These group emotions not only exacerbated sectional tensions leading to secession and war, but also lingered in the minds of many thousands of reluctant Confederates like Smith after the mourning period wore off, spawning doubt, dissent, and sometimes even disloyalty in the prospective Southern nation. [xix]

David T. Dixon is the author of Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General. He is currently writing a monograph focused on emotions and allegiance.

Sources:

[i] William Russell Smith to Wilhemena Smith, Jan. 12, 1861, William Russell Smith Papers, 1860-1903, Library of Congress.

[ii] For a similar discussion of emotions and allegiance in a biographical work, see David T. Dixon, “Augustus R. Wright and the Loyalty of the Heart,” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, Vol. XCIV, No. 3 (Fall 2010), 342—71.

[iii] To understand the impact of emotions in politics, see James M. Jasper, The Emotions of Protest (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2018). For a comprehensive discussion of loyalty, read Eric Felton, Loyalty: The Vexing Virtue (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011).

[iv] Benjamin Buford Williams, A Literary History of Alabama: The Nineteenth Century (Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press), 1979, 28—38.

[v] Bangor Daily Journal, Oct. 1, 1860.

[vi] William Russell Smith, The History and Debates of the Convention of the People of Alabama, Begun and held in the City of Montgomery, on the Seventh day of January, 1861 in which is Preserved the Speeches of the Secret Sessions, and Many Valuable State Papers (Montgomery: White, Pfister & Co., 1861).

[vii] William Russell Smith to Wilhemena Smith, Jan. 10, 1861, William Russell Smith Papers, 1860-1903, Library of Congress.

[viii] Smith, History and Debates of the Convention, 24—26.

[ix] Smith, History and Debates of the Convention, 27—28.

[x] Smith, History and Debates of the Convention, 31—33, 43—49.

[xi] William Russell Smith to Wilhemena Smith, Jan. 9, 1861, William Russell Smith Papers, 1860-1903, Library of Congress. Smith, History and Debates of the Convention, 50—55, 68.

[xii] Smith, History and Debates of the Convention, 68—69. William Russell Smith to Wilhemena Smith, Jan. 10, 1861, William Russell Smith Papers, 1860-1903, Library of Congress.

[xiii] Smith, History and Debates of the Convention, 72—75.

[xiv] Smith, History and Debates of the Convention, iv—v.

[xv] William Russell Smith to Wilhemena Smith, Jan. 12, 1861, William Russell Smith Papers, 1860-1903, Library of Congress.

[xvi] William Russell Smith to Wilhemena Smith, Jan. 12,17, 1861, William Russell Smith Papers, 1860-1903, Library of Congress.

[xvii] Smith, History and Debates of the Convention, 103—104, 120—21 .

[xviii] William Russell Smith to Wilhemena Smith, Jan. 24, Apr.14 1861, Feb. 27, 1862, Feb. 8, 1863, William Russell Smith Papers, 1860-1903, Library of Congress.

[xix] For his “affective theory of allegiance” and the idea that mourning rituals helped Unionists come to terms with secession and cooperate with the Confederate government, see Michael E. Woods, Emotional and Sectional Conflict in the Antebellum United States (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Thanks for this. IMO we need more of this sort of history. I won’t say that this has been suppressed, but the “war between the states” narrative left little room for this sort of nuance.

Excellent article! You’re right that we need deeper studies of the moral and emotional dilemma faced by Southerners during this crisis.

Brilliant! I am inspired. As it was then, so it seems to be now.

He simply did the right thing as the founders intended. He didn’t allow blind emotion overrule proper allegiance to his State.

Many leading Southern statesmen, including Jeff Davis and Alex Stevens, wanted the Union to work. But when faced with the reality that sectional differences, and sectional despotism on the part of the North, meant a failed union from the start, union did not take precedent over freedom. Union cannot exist where one section seeks to dominate and exploit.

Dominate and exploit? Bold choice of words to describe the southern states who seemed more than happy to do their own “dominating and exploiting” of people. Sectional despotism? You mean like passing the Fugitive Slave Act to force northern states to do what southern ones wanted?

I am not stating that I see ‘Rod’ above as necessarily correct and yourself as ‘incorrect’.

Rather, with your response, specifically, I don’t doubt the sincerity with which you express them. And, I understand the arguments that drive them.

But, can I ask you to ‘step back’ and try to look at the history you cite from a further vantage?

If you are citing the institution of slavery in both points, allow me to pose, ‘have you considered that the North was fully aware of what it would necessarily entail and if so, then how could the North have ever agreed to form a country with the South?’

How could the North disavow responsibility to the institution, and/or, to articulate it as ‘it was all the South’s fault!’ when it agreed to the 3/5 and Fugitive Slave tenets in the constitution that bound them?

Hello Rod and thanks for reading my post. I need to emphasize my view, based on my own studies and research done by social psychologists. There is no such thing as the “blind emotion” you speak of here. Emotions and reason work together to inform political views and virtually all thinking in the human brain. This is particularly true when it comes to political allegiance, as I point out in the post. The outdated and inaccurate view that emotion is the enemy and opposite of reason has been thoroughly debunked by social scientists. Historians would do well to consider this interplay when forming conclusions about a particular person’s decisions regarding loyalty.

Superb article! Fantastic work!

Thank you for sharing this research and the reminders of the intensely personal decisions that were made.