The 20th Massachusetts, Anton Steffens, and the Street Fight at Fredericksburg

ECW welcomes guest author Robert Dame

My grandfather Edgar (b 1900, d 1989) was a great storyteller. One tale about his own childhood concerned his mother Clara (b 1854, d 1920) sending him outside to pick flowers each year on the date of her older brother’s birthday. The story centered on his mother Clara’s sadness, and her tears. Clara, even by 1910, had not forgotten her older brother who went away to war way back in 1861 and never returned.

I would like to say this touching story, told to me in the 1970s, had a profound impact on me as a child. But we grandkids, being kids after all, were instead bemused by Grandpa’s endless jokes and stories about a far cooler thing: his missing finger, lost in a factory accident. Only later in life did I develop an interest in Civil War history.

Clara’s older brother who went off to war in 1861 was my great uncle Anton Steffens, born in the Kingdom of Prussia (modern day Germany), near the town of Koblenz.

His family became so-called “Forty Eighters“, fleeing to the United States after failed 1848 democratic revolutions against European monarchy. After his father became disabled, young Anton supported his parents and three siblings by working as a brass finisher. In July 1861 at age 18, he enlisted for three years in the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, serving in one of its two companies recruited from Boston’s fervently abolitionist German community.

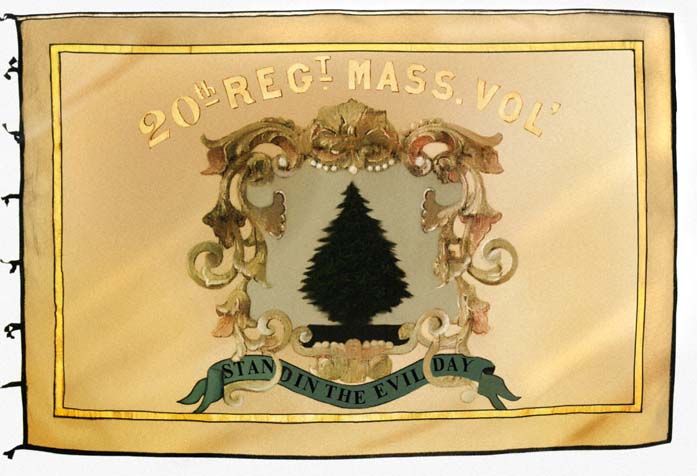

General Andrew A. Humphreys, Chief of Staff of the Army of the Potomac, called the 20th Massachusetts one of the very best regiments in the service. The 20th was also known as the Harvard Regiment because its officer corps was filled with Boston Brahmin students and graduates of the Ivy League institution. The Regiment won its reputation not from its star roster, but from hard fighting in Virginia as part of the Second Corps, Army of the Potomac. By war’s end, the 20th had the highest number of casualties among Massachusetts regiments, and of over two thousand total Union regiments in the War ranked fifth in casualties.

Private Anton Steffens and his regiment received their baptism of fire in October 1861 in the small-scale but significant engagement at Ball’s Bluff near Leesburg, Virginia. In 1862, Steffens served through the entirety of McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign from March to July, including the Seven Days battles at Fair Oaks, Glendale and Malvern Hill. The 20th and Anton then fought at the bloody battle of Antietam in September.

Anton Steffens met his fate three months later at the Battle of Fredericksburg. On December 11, 1862, Union General Ambrose Burnside, unable to complete the building of pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River due to Confederate sharpshooters and anxious to get his Army into the city before dark, approved a risky military move, a river crossing under fire.While the 20th and a few other regiments did make it across in boats, they were still hemmed in and needed to push the Confederates out of the town.

The 20th ended up as the vanguard to enforce a suicidal order to clear the streets. In column of companies the regiment charged its way through the city exposed to a terrible fire from the slowly retreating Confederates, who hid in buildings and behind fences. The regiment’s casualties in the space of a few city blocks were 138 wounded and 25 killed, including the loss of now-Corporal Anton Steffens.

Was my ancestor sacrificed due to a petty rivalry between college classmates? The following Civil War anecdote, detailed by no less an authority than Douglas Southall Freeman, can nonetheless be characterized as “too good to be true.” Confederate Lieutenant Lane Brandon, leading the 21st Mississippi Infantry in Fredericksburg, heard that his Harvard classmate and friend Captain Henry Abbott of the 20th Massachusetts was nearby. Defying orders to withdraw from the town, the stubborn Harvard man pushed his Confederates to keep shooting, presumably to ensure his later bragging rights at class reunions. Lane Brandon was put under arrest by his superiors before he finally withdrew his men. Perhaps it is karmic justice to my family that my older brother Tom has risen to become a stubborn Harvard man, specifically a Harvard Professor of Astronomy.

The reason Lane Brandon and his Confederates were withdrawing, was that their mission was a success. The delays had allowed General Lee to concentrate his forces on the ridgeline west of Fredericksburg. Holding the high ground, in the main battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, the Confederates inflicted a horrific defeat to the Union cause. Despite the overall debacle, or perhaps in some measure because of it, the successful December 11 river crossing and street fight was celebrated in the North in prose, poetry and art. An example of the prose, from Harper’s Weekly, December 27, 1862 issue: “It was an authentic piece of human heroism, which moves men as nothing else can….The country will not forget that little band.” An example of the poetry is “The Crossing at Fredericksburg”(1864) by noted poet and diplomat George Henry Bokker, inspired in part by an interview with Oliver Wendell Holmes, who did not participate in the battle (a theme picked up below). As to the art, I have a personal collection of ten distinct prints of the December 11 action, from the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, including contemporary historical artist Don Troiani’s work, “Fire on Caroline Street”.

Speaking again of karmic justice, a measure of it may also have occurred at Gettysburg six months after the Fredericksburg battle. Absent Anton Steffens, the 20th as usual was in the thick of the worst fighting, but this time, they were playing defense against a brave suicidal charge. The Twentieth’s officers yelled, “Now we shall give them Fredericksburg!” as they helped repel Pickett’s Charge.

The December 11 charge also received encomiums from a major figure in American history. In 1884, the most famous of all Harvard Regiment veterans, future US Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., delivered a Memorial Day address usually titled by its iconic phrase, “In Our Youth Our Hearts Were Touched with Fire.” The speech contained a vivid description of Holmes’ close friend Henry Abbott leading the charge, including this sentence: “His few surviving companions will never forget the awful spectacle of his advance alone with his company in the streets of Fredericksburg.”

Holmes’ description of Henry Abbott’s heroism led many to assume that Holmes himself was one of the “few surviving companions” and witnessed the “awful spectacle.” Though serving with the Twentieth, Holmes was sick on December 11, and was in fact located safely across the river. In fairness to the “Great Dissenter,” he served honorably and bravely in the Civil War, suffering three separate wounds, two of which were life-threatening. Still, Holmes suffered guilt from his absence on December 11 during the regiment’s most perilous fight, due to dysentery: “Oh what self reproaches I have gone through for what I could not help,” he wrote in a December 14 letter. Perhaps his angst inspired him to write such a memorable literary tribute to the charge.

A final (pun intended) issue regarding our family hero Anton Steffens concerns his final resting place. Richard Miller’s regimental history cites a soldier who witnessed a quick mass burial of the regiment’s enlisted killed on December 11, adjacent to the street where they fell. Burial on the battlefield is in accord with thousands of years of military tradition. After the Civil War was over, that tradition changed, when the notion was embraced that Union soldiers deserved burial in a proper national cemetery. Starting in 1866, Civil War Union dead of Fredericksburg, most unidentified, were re-interred in the nearby National Cemetery. Logic would suggest Anton Steffens is resting there. There is even an illogical “ghost story” to back it up. In December 2012, my younger brother Tim and I were walking in the National Cemetery, at dusk, after having witnessed the 150th Anniversary reenactment of the Fredericksburg street fight. Looking down at the green grass, out of nowhere appeared green cash–$26 in modern US currency, on the ground! “Must be a sign from Great Uncle Anton, telling us he is here,” said Tim. (As long as Great Uncle Anton had access to a heavenly ATM, $1,000 would have been an even better sign.)

Case closed? Hold on, there is a dissenting opinion, from the living. My beloved Aunt Mary’s hobby of family history and genealogy led her to connect with a relative by marriage, Jack. He had visited the Steffens family plot in Boston in the 1960s, and believes Anton Steffens rests there next to family members. . I immediately asked the most critical question: the answer was no, cash had never appeared at the gravesite. All kidding aside, this gentleman, who knew my grandfather’s brother, has the belief that Anton Steffens’ body was at some point returned. A cemetery nameplate or memorial for fallen Civil War soldiers, even in the absence of a body , called a “cenotaph”, was very common, and could have led to understandable confusion decades later. But if I understand correctly, that is not the case here. Could the cemetery’s records be checked? No- a fire has destroyed these records.

When I retire in a few years, I will have more time to try and definitively resolve this issue, if it can be resolved, and moreover learn as much as possible about Anton Steffens and his service. (We would know a lot more, if my Dad as a toddler in the 1930s had not thrown a bundle of German-language wartime letters written by Anton, out the attic window as a lark.) In any event, it won’t be this rank amateur, but wonderful, patient, helpful professional historians, who will lead me to the proper sources, if they exist, to learn more about my ancestor. (A little buttering up never hurts.) Also, based on recent family events, I must polish up on my storytelling skills. I have no missing finger, so never can be as amusing a grandpa as Edgar was; but do at least have that “ghost story” to share with my first grandchild, Elliot.

SOURCES:

Bowen, James l. “Massachusetts in the War, 1861-1865” (1889).

Bruce, George A. “The Twentieth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1865”. (1906) pp. 197-204, 221.

Freeman, Douglas Southall. “Lee’s Lieutenants: A Study in Command” (1944) p.403.

Howe, Mark. “Touched With Fire: Civil War Letters and Diary of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.”(2000).

Mackowski and White, “Simply Murder: The Battle of Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862” (2017) p. 24

Miller, Richard. “Harvard’s Civil War: A History of the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry” (2005) pp. 189-206, 269.

Miller and Mooney, “The Civil War: The Nantucket Experience” (1994).

Matteson, John. “A Worse Place Than Hell: How the Civil War Battle of Fredericksburg Changed a Nation” (2021).

Posner, Richard. “The Essential Holmes” (1992) pp 80-87.

Rice, Thomas. “Fallen Leaves: The Civil War Letters of Henry Livermore Abbott” (1991).

Does the author of this post not have a name? (Oops!)

Thanks for catching that – I’ve edited it in. This post comes from Robert Dame.

Aw!!! Many of us are on similar journeys, finding and bringing new life to dead relatives. “We see dead people.”

You’d better lock any sources you have up now; Elliot could have inherited Chet’s throwing arm and potentially his lack of respect for Civil War documents.

Beautiful job, Bob! Made us so proud to have been related to such a patriotic person as Anton. It was thrilling to read so many of the details of what his service entailed. May you continue to research this amazing story. Generations to come will be grateful, especially Elliot.

Well researched and written, Bob. Thank you for sharing. My grandfather, Edgar, told me of this story, but never in such detail. Interestingly, on my father’s side of the family, my great (x3) grandfather fought for the South with the in the same battles.

Robert, thank you for sharing about your ancestor. The 20th Massachusetts is one of my favorite regiments, and it’s always great to see a fresh account about a soldier in the ranks.

If Mr. Dame is reading this, I am highly intrigued for multiple reasons. For one thing, my great-great grandfather Michael Sullivan was wounded at Fredericksburg in the MA 20th, and I am curious as to where you found the picture. Another thing is that there is a branch of my family tree with the name Dame. It would be crazy if we were distantly related. Please feel free to get in contact with me, as I have many questions about where you found the picture of Anton, and if there are any other pictures of the 20th soldiers. In addition to that maybe we can see if we really do have more than just this in common! Great article!

Mr. Sullivan, you can contact me via email at “robertdame@comcast.net”