Writing Kelly’s Ford

March 17, 2023. St. Patrick’s Day. The 160th anniversary of the battle of Kelly’s Ford.

When I was in 6th Grade, I wrote a book called “Cavalry in the Civil War.” The wide-ruled composition notebook holds 76 pages of “research” turned into summaries about a variety of cavalry related topics. The purpose clearly stated on the first page in the “Forward” (should be “Foreword”).

This book has been written for an information book, to tell about the cavalry, its battles, generals, the cavalrymen’s life, weapons and more. I hope this book is of use to you, if you have questions, please write to me at the address below [address redacted] and I will do my best to help.

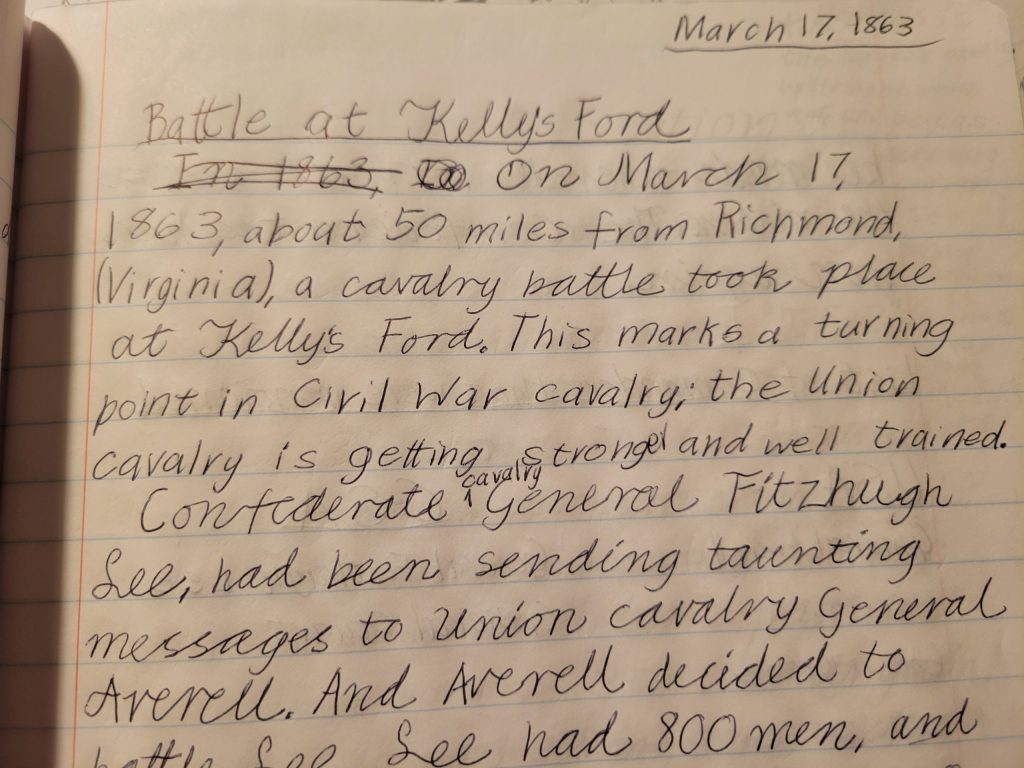

On pages 14-15, I wrote about Kelly’s Ford:

On pages 14-15, I wrote about Kelly’s Ford:

On March 17, 1863, about 50 miles from Richmond (Virginia), a cavalry battle took place at Kelly’s Ford. This marks a turning point in Civil War cavalry; the Union cavalry is getting stronger and well trained.

Confederate cavalry General Fitzhugh Lee, had been sending taunting messages to Union cavalry General Averell. And Averell decided to battle Lee. Lee had 800 men, and Averell had more than 2,000 men.

General Stuart was at Culpeper while the battle was going on. He unselfishly decided not to go help because, Lee was doing well. Stuart wanted Lee to win the glory for beating Averell and his men.

Lee fought so well that he made Averell retreat across the river. The Confederates had won again.

- Richmond is ~80 miles from Kelly’s Ford on the Rappahannock River (not 50 miles).

- Surprisingly, the troop numbers are in the right range: Union = 2,100 and Confederates = 800. Casualties totaled approximately 211, with 78 fallen in blue and 133 in gray.

- The interpretation of J.E.B. Stuart is a bit generous. Stuart did ride out to Kelly’s Ford, and he did let Lee continue to manage the battle. Older Sarah thinks it’s a bit of a stretch to say that Stuart took that approach simply to be unselfish.

- It’s also an interesting take that the Union retreated because the Confederates fought so well. Averell intentionally used a stone wall to shelter his dismounted cavalrymen and give them some experience in actually “standing up” to Confederate attacks. Yes, the Union force retreats, but there’s more to the story than “Lee fought so well.” Accounts from Kelly’s Ford can be a confusing mess at first study, but one thing that does become clearer is that the Confederate attacks were not strictly coordinated and sometimes their assaults went in piecemeal.

(For a more complete battle history of Kelly’s Ford, please refer to my 2019 post and this one about John Kelly.)

Aside from some nostalgia, why dig out this old “manuscript”? Well, this evening I’ll be writing about Kelly’s Ford again—with a little more nuance and a stack of citable sources. Among the “to be finished” chapters for a manuscript biograph of Major John Pelham are: Kelly’s Ford, Funeral, and Memory. I decided it would be meaningful to actually write those sections on the 160th anniversary of the battle and this young Confederate officer’s mortal wounding. How often does an author get the chance to write the ending on the fatal anniversary?

Pelham commanded batteries of the Stuart Horse Artillery and had gained international fame for himself during the battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. He had nearly graduated West Point, but chose secession in April 1861. During the first two years of the Civil War, Pelham had a stellar battlefield record, a tendency to take risks with his cannons, and a charisma that endeared him to comrades and acquaintances. On March 17, 1863, he joined General Stuart, rode out of Culpeper and toward the sounds of battle near Kelly’s Ford. Hours later, Pelham was mortally wounded. He died in the early morning of March 18, without regaining consciousness. A swift end to a short life, but the twisted beginning of Pelham’s story in historical memory.

Now, it’s been four years of study and wrestling to try to find an honest meaning to the young artillerist’s life. I’m pretty sure I’ve found my conclusion to draw about his life, death, and memory, but I suspect I’ll still struggle putting it into clear words tonight — trying to get it right, trying to be fair, trying to be balanced. But the death account and conclusion of a life has to be written sometime. The confusion of Kelly’s Ford sorted onto the page as carefully and honestly as possible. Why not tonight?

A couple weekends ago I spent some time “free writing” through some thoughts about Pelham, trying to prepare to draw a conclusion. I’m fairly certain this exact paragraph won’t make it into the manuscript, but it’s a bit of a teaser:

His death is a tragedy—it is tragedy when anyone dies, especially a young person who should have had their whole life to live. His death is shocking. Probably even to himself. Of all the times he should’ve died, it wasn’t at Kelly’s Ford.

I had an ancestor who was wounded at Kelly’s Ford on November 7, 1863. Sgt David Alva Barnett- Company B 99th Pennsylvania Infantry. He was transported to Douglas Hospital in Washington DC where his left leg was amputated. He died from blood poisoning on November 26, 1863. I have not been able to find any information about the actions of the 99th on that day or if any report of my ancestor’s wounding were made.( I have the contents of his file at National Archives- but no mention of how he was wounded or if family was notified). One author has told me the 99th was not involved in the action that day but the brief regimental history says they were ordered forward. If anyone has any information about that action or suggestions for research- please email me at rdsnyder1@comcast.net. Thank you , Richard Snyder -York,PA

Take a look at the latest book by Jeff Hunt. It covers the November 7 fight at Kelly’s Ford and the flight at Rappahannock Station that same day.

I’ve spoken with Mr Hunt via email. He had no information on the 99th PA or their actions that day- and he does not mention them in his book. Yet their regimental history states they were ordered to cross and did take casualties including an officer.

You’re such a brilliant writer – I look forward to all of your posts and work.

Refreshing to learn of a youth interested in history.

A child prodigy to boot.

The Civil War connected personally with so many of my generation who were in school during the Centennial. Thank you for sharing from your school days’ passion for the war!

In 1960, my parents took me to see the Gettysburg battlefield. I was hooked. But you, Sarah, are amazing. Love your posts, especially the one on Reveille. ECW is a great source for civil war info. I just love it.

Thank you for your kind words, Frank. Happy to hear that ECW provides you with helpful information and some extra inspiration.