Civil War Surprises: Santiago Vidaurri’s Tempting Offer

In 1861 the Confederacy dispatched envoys, diplomats, and agents abroad in attempts to secure foreign recognition and international prestige. The most well-known of these became the Trent affair. A far more obscure effort was that of José Augustín Quintero, a Cuban-born Texas resident. Enlisting in the Quitman Rifles in 1861, Quintero was quickly dispatched to northern Mexico as a government agent, with orders to engage Mexico’s leadership along the Texas border. Reaching the Mexican city of Monterrey by August 1861, Quintero was received with quite the surprise: an offer for the Confederacy to annex ten percent of Mexico!

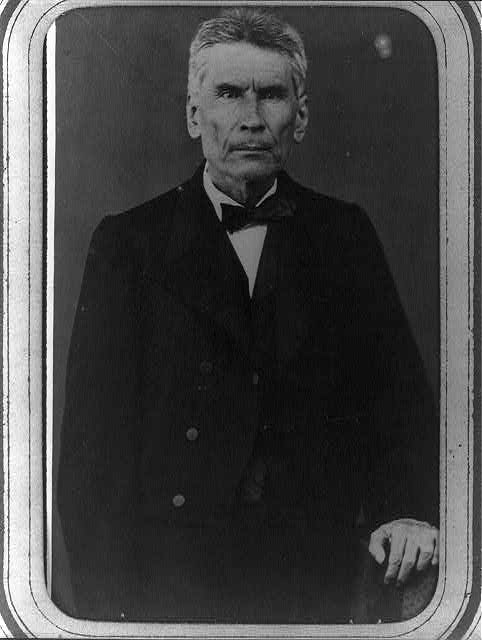

The annexation offer came from Santiago Vidaurri, governor of the merged states of Nuevo León and Coahuila. His domain was one of Mexico’s most contested areas. The states had been part of the failed attempts to create the Republic of the Rio Grande in 1840. They were invaded by US troops in 1846, and in 1856 Vidaurri annexed the adjacent state of Coahuila and unsuccessfully tried to create the Republic of the Sierra Madre. When Mexico’s War of the Reform began in 1858, Vidaurri’s enlarged Nuevo León sided with liberal leader Benito Juárez, essentially becoming supreme ruler over his territory by capitalizing on Mexico’s internal conflicts.

When the US Civil War began, Vidaurri sensed an opportunity, or at the very least feigned such. The Juárez government was attempting to solidify federal control over Mexico, which would limit Vidaurri’s influence. When Quintero reached Monterrey, Vidaurri offered his merged state to the Confederacy. Perhaps leaving Mexico and joining the new Davis government might guarantee his sovereignty over what historian R. Curtis Tyler styled Vidaurri’s “’kingdom’ on the Rio Grande.”[1] Perhaps instead it was a power play hinting to Jefferson Davis that Vidaurri might be friendly towards the Confederacy or that he wanted to use a friendly Confederacy to maintain sovereignty within Mexico or even try reforming the Republic of Sierra Madre. Regardless, rumors spread in Confederate newspapers of a proposition placing “the Northern States of Mexico into a union with the Southern Confederacy.”[2]

Briefly returning to Richmond, Quintero wrote letters on August 16, 17, and 19 to Confederate Secretary of State R.M.T. Hunter outlining the proposed annexation.[3] If legitimate, it would be quite the bonanza. A new state joining from a foreign government would boost the Confederacy’s land area and international prestige while creating a direct lifeline into Mexico for transfer of supplies no naval blockade could reach. Finally, it would realize aspirations of many Southerners who desired expansion of territory and slavery south.

Quintero’s letter with Vidaurri’s offer set off alarms in Richmond. In August and September 1861, the Confederacy’s highest aspirations were still being developed. That summer Confederate envoys signed treaties with Indigenous tribes in the Indian Territory, Confederate armies had a significant grasp of what would become West Virginia, troops were marching into Kentucky, battles for control of Missouri were being fought, and Lt. Col. John R. Baylor declared a Confederate Arizona Territory (confirming the Mesilla secessionist declaration of March 1861). To some in Richmond, Vidaurri’s offer was one more effort to expand the Confederacy.

Even if Vidaurri’s offer was legitimate, the Davis administration had no serious interest in immediately annexing Nuevo León. “The President is much gratified to learn from so high an authority as Governor Vidaurri that the people of New Leon and the adjacent Provinces of northern Mexico are animated by such friendly feelings toward the Confederate States,” Assistant Secretary of State William Browne wrote to Quintero on September 2, but President Jefferson Davis was “of opinion, however, that it would be impudent and impolitic in the interest of both parties to take any steps at present in regard to the proposition made by Governor Vidaurri.”[4]

Nuevo León’s annexation would have surely brought a war declaration from Mexico as Juárez’s government simultaneously sought to repel French, British, and Spanish forces preparing to invade the country to recoup unpaid debts. It thus might also have caused conflict between the French-backed Maximilian in 1864 when he assumed Mexico’s throne.

Jefferson Davis did not abandon thoughts on future annexation, ordering José Quintero back to northern Mexico to leverage good relations with Vidaurri and “collect and transmit” information about Nuevo León including population “divided into races and classes, the superficial area of the several provinces, their products, mineral resources, &c., the amount and value of their exports and imports, the state and extent of their manufactures, and the general condition of the people.”[5]

Quintero also had instructions to get Governor Vidaurri to ease trade relations to export cotton and purchase arms while also extending good relations with the Confederacy to the governors of nearby Chihuahua and Sonora, hoping Mexico’s northern states might “unite … in a protest to the Mexican Government” over state sovereignty.[6] Such a move might tip the balance in the continent with the Confederacy possibly gaining favor in all of Mexico’s northern territory as the central Juárez government collapsed under French pressure. Vidaurri remained sympathetic, even condoning the flying of Confederate flags over Monterrey on July 4, 1863, and his influence spread further when he was temporarily appointed to command Tamaulipas and its vital port of Matamoros.[7]

When Benito Juárez’s government moved north to both regain control over northern Mexico and avoid collapse, Vidaurri escaped into exile in Texas temporarily, but returned to Mexico as a new supporter of Maximilian’s regime. He was captured by pro-Juárez cavalry and executed in 1867 as Maximilian’s government collapsed.[8] Quintero remained an agent in Monterrey, returning to the United States to receive a postwar pardon in late 1865.[9]

Santiago Vidaurri’s offer to cede greater Nuevo León to the Confederacy was an attempt by the governor to consolidate power and sovereignty over his territory. With internal and external threats facing Vidaurri and all of Mexico, it is clear why Jefferson Davis refused the offer, but even if the Confederacy would have acquired these Mexican lands, that opens up hypothetical considerations that would have impacted the US Civil War’s course:

- Would Confederate General Henry H. Sibley have marched into Confederate Arizona in 1862 seeking conquest of New Mexico, or instead march south to secure the border with Mexico?

- Would Mexico and the Confederacy fight a war over Nuevo León?

- Would other states join Nuevo León’s annexation?

- Nuevo León allowed debt peonage, but not African enslavement. Would the Confederacy pressure Vidaurri to legalize slavery, would this be an argument postponed until after the war, or would the Confederacy acquiesce that debt peonage was close enough to slavery? (ECW previously explored debt peonage here and here)

- If Mexican states joined the Confederacy as European powers invaded, would the US extend the blockade to Mexico? For reference the French established blockades of Mexican ports as they entered the country, such as the French blockade of Acapulco in 1864.[10]

- Even if Sibley would have historically completed the 1862 New Mexico campaign, would his forces then proceed to Nuevo León instead of Louisiana, thus impacting Louisiana campaigns in 1863/1864? Would US forces in New Mexico invade Nuevo León via Texas?

- Would a Confederate Nuevo León create hostile relations with Maximilian’s government or Napoleon III in France?

- Would the US desire to keep Nuevo León after the war if it belonged to the Confederacy or would it return those lands to Mexico?

- Would Nuevo León become a postwar haven via a reconstituted Republic of the Sierra Madre for Confederates to escape into? How would this impact the war’s end, exile of Confederate leadership, and Reconstruction? Would the US allow such a republic to exist if it became de facto just another Confederacy?

Regardless, there was much militarily, diplomatically, and economically at stake in August and September 1861 when Santiago Vidaurri made the surprise offer to allow annexation of greater Nuevo León by the Confederacy.

Endnotes:

[1] R. Curtis Tyler, “Santiago Vidaurri and the Confederacy,” The Americas, Vol. 26, No. 1, July 1969, 68.

[2] “Prospective Union,” Richmond Whig, September 3, 1861. See also “Later from Texas,” New Orleans Daily Picayune, September 7, 1861.

[3] Quintero to Hunter, August 16, 17, and 19, 1861, Confederate States of America Records, Library of Congress.

[4] Browne to Quintero, September 3, 1861, Messages and Papers of the Confederacy, James D. Richardson, ed., (Nashville, TN: United States Publishing Company, 1906), Vol. 2, 78.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Browne to Quintero, December 9, 1861, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Ser. 2, Vol. 3, 308.

[7] Quintero to Hunter, July 8, 1863, Confederate States of America Records, Library of Congress.

[8] Edward H. Moseley, “Vidaurri, Santiago,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed April 02, 2023, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/vidaurri-santiago.

[9] Quintero to Andrew Johnson, November 20, 1865, Texas, J.A. Quintero, Case Files of Applications from Former Confederates for Presidential Pardons, 1865-67, M1003, RG 94, US National Archives.

[10] Robert Erwin Johnson, Thence Round Cape Horn, (Annapolis MD, US Naval Institute Press, 1963), 120.

Great piece. I ran into Quintero myself during my research for my first book. He accompanied Texas Unionist Charles Anderson’s wife and two daughters on their forced emigration to Brownsville, Texas in August 1861. Quintero kept a close eye on the Andersons and tried to get information from them. Both daughters mention him in their diaries at the Briscoe Center at the University of Texas.

Interesting how Chatelain desperately attempts to keep the “expansion of slavery” myth alive and well in this piece in spite of the evidence.

First he says the offer by Vidaurri’s offer: “would realize aspirations of many Southerners who desired expansion of territory and slavery south.” Here the seed of a fabrication is sown so that the reader will continue to believe that the South desired to “expand slavery,” in spite of the fact that Davis’ rejection of Vidaurri’s offer is evidence of exactly the opposite.

Never mind that when it was legal to “expand slavery” in the Kansas Territories (1855 to 1860), the slave population there went from 66 down to 2, the fabrication that the South “desired to expand slavery” must be kept alive. Despite the fact that in an 1850 Senate speech Jeff Davis stated the only reason the South wanted to take slaves into the territories was for emancipation, the “desire to expand slavery” myth must be kept alive. Despite the fact that John C. Calhoun’s 1849 letter to the Southern Constituency, signed off on by 40+ Southern Representatives stated that the South did not want to expand slavery, the “desire to expand slavery” myth must be kept alive. Despite the fact that Northern anti-slavery Senator Daniel Webster had, in an 1849 speech, stated emphatically that the semi-tropical institution of slavery would never go into the arid climates of the West because it could not be profitable there, the “desire to expand slavery” myth must be kept alive.

Davis’ rejection of the offer must then be spun as a fear of starting a war with Juarez’s government in spite of the South’s desire to expand slavery in Mexico. Never mind that Davis turned down the offer, explicitly stating “it would be impudent and impolitic in the interest of both parties,” we must be led to believe that Davis turned down a golden opportunity, for a bondage addicted South, to expand slavery out of fear. Are we to really to believe the spin that Juarez, facing possible war with Britain, France, and Spain, would have added the CSA to that mix to keep Nuevo Leon? Isn’t it more likely that Davis, a man of the highest respect for law, really did consider it “impudent” to seek the annexation of a section of Mexico without negotiations with the Mexican government? In reality there was no ambition to expand slavery, much less in a climate that even Daniel Webster admitted was not conducive to slave labor.

What Chatelain either does not know, or is attempting to ignore to promote the expansion of slavery myth, is that the CSA’s Trent diplomats he briefly mentions in this piece are at that very time negotiating an end to slavery with Britain and France in exchange for aid in securing independence for the Confederacy. The CSA did not secede to “preserve and expand slavery” as its January 1862 offer to end slavery makes crystal clear.

Pro-Union border slave State Representatives met with Lincoln on July 12, 1862 confirming the CSA’s offer to end slavery, warning him of:

“the fact, now become history, that the leaders of the Southern rebellion have offered to abolish slavery amongst them as a condition to foreign intervention in favor of their independence as a nation. If they can give up slavery to destroy the Union; We can surely ask our people to consider the question of Emancipation to save the Union.”

(Border State Congressmen to Abraham Lincoln in a meeting July 12, 1862, recounted in a letter dated Tuesday, July 15, 1862.)

The very next day after meeting with these border State Representatives, Lincoln sits down and pens his own Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Something he had long resisted doing, and something he felt it unlawful for him to do. Yet now he was willing to break the law and why? It was Lincoln who feared a war; a war with Britain and France joining forces with the CSA. Lincoln was willing to break the Constitution to preempt the CSA’s offer of emancipation with his own proclamation.

Hey Rod, thanks for your comments (some of which I completely agree with and some I do not), though I would say you are making a major assumption of my writing that I am equating Southerners with Confederate leadership. My original statement was that acquisition of greater Nuevo León “would realize aspirations of many Southerners who desired expansion of territory and slavery south.” Those expansionist aspirations existed before states seceded and formed the Confederacy, thus why I did not say that such an expansion would realize Confederate government expansionist ambitions. The Confederacy was not opposed to territorial growth. They admitted Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas, and the Arizona Territory after the Confederacy’s formation. But, you are right that Jefferson Davis publicly proclaimed in April 1861 that his government “seek no conquest, no aggrandizement, no concession of any kind from the states with which we have lately confederated.” (Davis to the Confederate Congress, April 29, 1861, Dunbar Rowland, Jefferson Davis Constitutionalist: His Letters, Papers, and Speeches, (Jackson, MS: Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 1923), Vol. 5, 84).

Instead, I mentioned a desire by “many Southerners” to expand slavery. That includes Jefferson Davis (“The Pacific is in many respects adapted to slave labor and many of the citizens desire its introduction.” – Davis to Cannon, December 7, 1855, William J. Cooper, Ed., Jefferson Davis: The Essential Writings, (New York, 2003), 115). Prominent Kentucky minister Robert J. Breckinridge wrote of his desire to take “possession of the whole southern part of this Continent, down to the Isthmus of Darien” (Benjamin Morgan Palmer, A Vindication of Secession and the South from the Strictures of Reverend R.J. Breckinridge DD LLD in the Danville Quarterly Review (Columbia, SC: Southern Guardian Press, 1861), 24). In December 1860 a Georgia newspaper proclaimed “the dominant race will supplant all others, and slavery will expand South to Brazil and from her till stopped by snow” (“Disunion,” The Daily Constitutionalist, Augusta, Georgia, December 30, 1860). In 1858 Mississippi Senator Albert G. Brown proclaimed “I want Cuba, and I know that sooner or later we must have it; if the worm eaten throne of Spain is willing to give it up – for a fair equivalent If not, we must take it. I want Tamaulipas, Potosi, and one or two other Mexican States; and I want them all for the same reason – for the planting and spreading of Slavery.” (“Political,” Anti-Slavery Bugle, Lisbon OH, November 27, 1858.)

Alabama State Senator Lewis Stone debated in January 1861 that “Arizona and Mexico, Central America and Cuba, all may yet be embraced within the limits of our Southern Republic. … Should the border States refuse to unite their destiny with ours, then we may be compelled to look for territorial strength and for political power to those rich and beautiful lands that lie upon our South-western frontier (“Debate of the African Slave Trade Resumed,” January 25 1861, William R. Smith, The History Debates of the Convention of the People of Alabama Begun and Held in the City of Montgomery (Montgomery, AL: White, Pfister, and Co, 1861, 237). Was this every Southerner’s belief? No, especially those Southerners who were enslaved. Did “many Southerners” hold similar thoughts as I claim. Yes.

I agree that Davis rejected the offer with his words at face value, as it was “imprudent and impolitic in the interest of both parties.” Lastly, the Juárez government would have surely risked war to keep Nuevo León, as loyal Juárez forces literally invaded Nuevo León and deposed Vidaurri in 1864 even as French forces marched on Mexico City.

As a preliminary aside, you are conflating the desire to expand slavery with that of expanding the number of slaveholding states in order to sure the survival of the institution where it existed. More importantly, there is not a jot of evidence that the CS government wanted to end slavery in July 1862 and made an offer to do so. And a mountain range of evidence to the contrary.

There is indeed a great deal of evidence that the Confederacy considered a long-range plan of emancipation in 1862.

A treaty outlining this was nearly-clinched by January of 1862 between the CSA, Britain and France. This treaty stipulated, in addition to matters of trade, etc, in exchange for British/French recognition of the CSA as a sovereign nation and their intervention in the war, all Black Americans in the CSA who would otherwise be born into slavery were to be born as Free Persons of Colour.

Obviously, this was far from perfect, to say the very least. Slavery would be phased out over time, and it’s worth noting that this is how slavery came to an end in most Northern states in the early 1800s; by Emancipationist designs that phased it out slowly.

you’re absolutely correct — not an iota of primary source evidence that the CSA had any intention of getting rid of slavery.

Mark Harnitchek-

Do you really want to go down this path again?

The short and sweet is, no; there is a large amount of evidence to prove that the South looked to abolish slavery.

Just the other day, I was reading Mason’s report to Judah Benjamin about his interviews with British Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, re. the Duncan F. Kenner Mission in 1865.

And the last I tallied up, there were about 30 newspaper clippings from around the British Empire simultaneously that wrote of the near-clinched 1862 Confederate Emancipation Treaty with Britain and France.

These are all the tips of the iceberg.

If you want to argue the Union was the first to actually action a policy of emancipation, that’s something else.

Even a brief reading about the American Southwest, the area with Hispanic influence, nomadic Indian tribes, fur trappers, ranchers and miners, makes you realize what a permeable membrane this whole area was. The entire area designated as “Mexico” was not immune to this. It had more regional identification than national, having, as Santiago demonstrated, a near feudal governing structure. You realize that what was true then is in many ways still true today.

This is a superb article that sheds light on a very-under researched aspect of the war! There are a few key points to expand on-

1) Davis’ main hesitations to annexing Vidaurri’s provinces were twofold; (i) this would put the Confederate trade routes through Mexico and to its shores in danger of being attacked by the Union. This trade route was vital to the Confederacy being able to acquire military supplies. (ii) France was in the process of the invading and colonising Mexico and Davis desired to yet win French recognition and intervention.

2) The great insight about this possible annexation was that Vidaurri was one of the most aggressive Abolitionists on the planet and all through the 1840s and 50s, he had stymied all manner of attempts by the Texas government, US federal government and private American slave owners to attempt to enter his areas to recapture fugitive slaves. He would also not hand back the many fugitive slaves who made it to his provinces.

Had the annexation gone through, Vidaurri would have insisted that his provinces be annexed to the state of Texas itself, not as either Confederate national territories or territories administered by the state of Texas; only as part of Texas itself.

Why? Because then the Texas legislature would have declared these areas off-limits to slavery. In the CSA, the federal government could not pass laws affecting slavery. This was the exclusive jurisdiction of the individual states.

Thank you for posting this piece. I was unaware of this interesting twist of history.