Civil War Surprises—The Blockade Proclamation: An Act of International War

One week after the fall of Fort Sumter, April 19, 1861, President Lincoln issued an emergency war proclamation implementing a seaborn blockade of the Confederacy, one of his first major decisions. This was a bold and contentious strategy for a novice commander in chief who was determined to interdict ocean commerce with states in rebellion, starving them of funds, war materials, and necessities.

One week after the fall of Fort Sumter, April 19, 1861, President Lincoln issued an emergency war proclamation implementing a seaborn blockade of the Confederacy, one of his first major decisions. This was a bold and contentious strategy for a novice commander in chief who was determined to interdict ocean commerce with states in rebellion, starving them of funds, war materials, and necessities.

Lincoln’s proclamation was an unpleasant surprise for Great Britain. Advisors had proposed that the president simply declare southern ports administratively closed, providing the navy an excuse to turn back merchant vessels under the guise of enforcing customs laws and duties not collectable in rebel-controlled harbors.

During a dinner at the British legation in March 1861, Secretary of State Seward tested the waters with Ambassador Lord Lyons, suggesting that warships would be stationed off the coast for this purpose. Lyons responded directly: “If the United States determined to stop by force so important a commerce as that of Great Britain with the cotton-growing States, I could not answer for what might happen. . . . An immense pressure would be put upon Her Majesty’s Government to use all the means in their power to open these ports.”[1]

Foreign vessels, primarily British, carried most of the South’s seaborn trade especially now that Yankees were out of the business. Obstructing peaceful passage of their merchant vessels was an act of war against them. Lincoln could not strangle the rebellion this way. He could not even halt the import of weapons and military supplies—legitimate items of foreign commerce—upon which Confederate armies depended.

The alternative was a formal blockade in international law, which was itself an act of war between nations. But Lincoln insisted that the Confederacy was not a nation; the United States was fighting a rebellion not a war. Despite this glaring inconsistency, the president issued his proclamation. The possibility of another war with Great Britain over trade became real and immediate.

The blockade became the primary mission of the United States Navy, unprecedented in extent as the largest, longest, and most expensive military campaign of the war, viewed by many on both sides of the Atlantic as impossible. The blockade constituted a discrete naval zone of operations with monumental challenges over 3,500 miles of Atlantic and Gulf coast from the surf out to several miles seaward.

The mission was unprecedented in strategy: Previous blockades—most recently Great Britain’s enormous effort during the French wars of revolution and empire early in the century—concentrated on confining enemy naval forces in key ports to impede them from challenging command of the sea and from invading colonies or homeland. Disruption of their seaborne commerce was a secondary consideration.

The mission was unprecedented in strategy: Previous blockades—most recently Great Britain’s enormous effort during the French wars of revolution and empire early in the century—concentrated on confining enemy naval forces in key ports to impede them from challenging command of the sea and from invading colonies or homeland. Disruption of their seaborne commerce was a secondary consideration.

The president and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles thought differently, envisioning the most ambitious blockade ever attempted, suppressing ingress and egress of countless trading vessels of all nations to and from hundreds of estuaries, bays, harbors, and streams, large and small. Welles formed a Blockade Strategy Board as a rudimentary general staff to make recommendations.

The mission was unprecedented in technology: Secretary Welles undertook an immense, unparalleled warship procurement and building program arming almost anything that could float including tugs, ferries, or merchant vessels of all sizes and shapes while constructing new warship classes to novel designs with advanced industrial manufacture, particularly for ironclads. Within two years, the fleet surged from a third-rate force of less than 100 ships to over 600 war vessels, one of the largest, most powerful, and technologically advanced in the world.

Modern steam propulsion enabled blockaders to maintain station off Rebel ports more consistently than wind ships but presented emergent difficulties in ship maintenance and fuel supply. Steam also furnished the Rebels a new class of sleek, fast blockade runners, which frequently outran and outmaneuvered pursuers.

Modern steam propulsion enabled blockaders to maintain station off Rebel ports more consistently than wind ships but presented emergent difficulties in ship maintenance and fuel supply. Steam also furnished the Rebels a new class of sleek, fast blockade runners, which frequently outran and outmaneuvered pursuers.

The mission was unprecedented in tactics: Although the U.S. Navy had never done much blockading, it inherited a robust tradition from its progenitor and former enemy, the Royal Navy. Lessons and tactics under sail were adopted from them augmented by innovative steam tactics for barriers afloat attempting to sight, catch, engage, and capture or destroy runners despite darkness, fog, and storm. A new operational unit was established—the squadron—encompassing masses of ships from dozens to hundreds and presenting additional challenges in command and control, signaling, and seamanship.

The North and South Atlantic Blockading Squadrons and the East and West Gulf Blockading Squadrons would surveil their respective areas. Having never deployed formations larger than a few ships (and worried about aristocratic class pretentions of admirals), the United States had not commissioned naval officers above the rank of captain (army colonel equivalent). In late 1862, admiral ranks were established to command the new squadrons and to operate on equal status with army general officer counterparts.

The mission was unprecedented in administration: Mid-century social reforms upended ancient traditions of the sea, patterns of promotion, and forms of discipline while a crude departmental bureaucracy faced immense trials in mass recruitment, training, and personnel management. The Navy exploded from 15,000 to 24,000 officers and men. Led by a core of salty veterans, a fresh generation of officers arose, steeped in modern technologies, educated at the new Naval Academy in Annapolis, and fired in the crucible of war. They were joined by a gaggle of newly minted volunteer officers from civilian pursuits, many with little maritime experience. The nascent position of naval engineer began to transform the ancient maritime profession.

The struggle also coalesced crewmen into a professional enlisted corps whose members belonged to the service rather than to individual warships. With the notable exception of rivermen in the heartland, crewmen on both sides of the conflict tended to come from the burgeoning industrial working classes of Northern and European cities rather than from rural towns and farms. Culturally distinct from soldiers, they fought a different war primarily from personal rather than ideological motivations including the promise—real but mostly unrealized—of prize money for captured blockade runners.

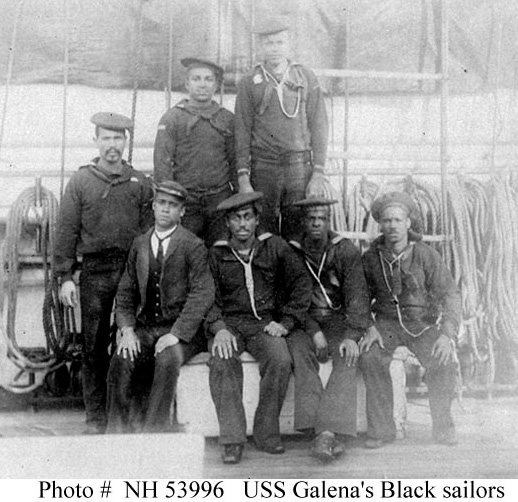

Officers were immersed in a multicultural ethos accustomed to the polyglot assemblage of transnational mariners who had more in common with each other than with homebound compatriots. Captains desperate for recruits of any shade from anywhere, trainable in hard and dangerous physical labor, looked on race or language as minor factors.

Freedmen and contrabands became integrated as seamen and combatants into U.S. Navy crews earlier, more quietly, on a more equal basis, and in proportionally larger numbers than into the army, even some into the Confederate navy. Life afloat was its own isolated world with authoritarian structures and firm discipline, customized through millennia to the unique requirements of managing huge, complex machines in a hostile environment, and hardly less strict in its way than slavery.

Meanwhile, Confederates sought to neutralize the blockade as a primary strategic objective. Southerners struggled to birth a navy from scratch, modeled after the enemy’s example, and facing the same trials exacerbated by acute shortage of maritime resources, infrastructure, and skills. Half of the U.S. Navy’s southern-born officers joined the rebellion, forming a cadre of expertise, some among the most talented. Crewmen frequently were diverted from the army over intense resistance from generals.

Led by its able secretary, Stephen R. Mallory, the Confederate Navy was more successful than should have been expected. Mallory focused on strategies of the underdog: commerce raiding and blockade running at sea, with defense of key fortified positions along interior lines ashore bolstered by asymmetric new technologies such as ironclads, torpedoes, and submarines. The new government bought, confiscated, and converted what few vessels it could acquire. It also undertook an extensive effort in Great Britain and France to purchase or construct commerce raiders, blockade runners, and ironclads, which elevated international tensions to the boiling point.

The blockade generated intense international controversy as Great Britain, the world hegemon in ocean commerce and naval power, sought to sustain essential trade with cotton states. Confederate leaders expected that reliance on cotton for British mills, referred to as “king cotton,” would induce them to break the blockade behind the guns of the Royal Navy. In a flourishing global economy fueled by industrialization and vast trade networks, ancient arguments resurfaced over the rights and responsibilities of neutral nations under international law, disturbing echoes of the Revolution and War of 1812. Britishers attracted by the lucrative trade funded, built, commanded, and manned many blockade runners.

The Queen’s ministers and Parliament, responding to severe political pressure, seriously debated intervention, which probably would have led to Confederate independence. They had no comfortably neutral position between American combatants, one of whom employed every stratagem to ensnare Great Britain in the dispute while the other insisted they would fight to keep her out. Union and Confederate navies sailed into the midst of this diplomatic maelstrom and contributed to it.

The Royal Navy West Indies Squadron prepared to break the blockade, invade (again) the Chesapeake perhaps in cooperation with Confederate forces, reinforce Canada, and with their far-flung squadrons, take American vessels wherever found. Under vociferous threats of war from Washington, however, the British finally declined to intervene, although that would not be evident for the first two war years.

No grand engagements occurred in the offshore blockade theater of operations and no national heroes arose. The most renowned squadron commanders, Admirals David G. Farragut and David D Porter, earned their reputations attacking Rebel ports and along heartland rivers. Other old salts like Louis M. Goldsborough, Samuel Phillips Lee (cousin to R.E. Lee), Samuel F. Du Pont, and John A. Dahlgren endured the thankless commands with little glory.

Thousands of storm-tossed and bored blockaders on hundreds of vessels watched over distant, undifferentiated sand dunes and swamps from the Chesapeake Bay to the Rio Grande while infrequently bursting into frenetic action for a few shots at a speeding Rebel runner. Many got through, but a significant number did not; many others did not try. Although quantitative conclusions are elusive, the blockade progressively constricted the Southern economy, deprived its citizens, and degraded home-front morale.

Thousands of storm-tossed and bored blockaders on hundreds of vessels watched over distant, undifferentiated sand dunes and swamps from the Chesapeake Bay to the Rio Grande while infrequently bursting into frenetic action for a few shots at a speeding Rebel runner. Many got through, but a significant number did not; many others did not try. Although quantitative conclusions are elusive, the blockade progressively constricted the Southern economy, deprived its citizens, and degraded home-front morale.

[1] Dean B. Mahin, One War at a Time: The International Dimensions of the American Civil War (Washington, D.C., 1999), 45-48.

The fact that the blockade was the “largest, longest, and most expensive military campaign of the war” is a great point Dwight! I’d never thought about it quite like that.

It might be an interesting thought experiment to consider how things would go if Britain did declare war.

Thanks Scott. The international elements of the war are fascinating. I recommend my essay on just that subject, “What If Great Britian Had Intervened in the American Civil War” In “The Great ‘What Ifs’ of the American Civil War: Historians Tackle the Conflict’s Most Intriguing Possibilities.” (Savas Beatie 2022), Chris Mackowski and Brian Matthew Jordan, editors.

Queen Victoria had to give the go ahead in order to allow GB to enter the American Civil War. And she had already declared GB to be neutral in the war.

A World Aflame is a good account of British/US relations

thanks Dwight … great point about the United States creating a blue (and brown) water Navy from whole cloth along the crews to man them — “polygot” is definitely the right descriptor… another good example of the loyal states economic and industrial power … and President Lincoln took a risk declaring the blockade, but he got away with it … he was arguably one of the nation’s best commander in chief … a role that he created from whole cloth … thanks again for the great post.

The early threadbare blockade was given aid from an unexpected quarter – the Confederate embargo on cotton exports. By the time this policy was dropped, the Union Navy had acquired enough ships to start having a real effect.

Trying to black-mail Great Britain, just wasn’t an effective policy.