Back Along Jackson’s Flank March

“You may go forward then,” the general said.

His subordinate, Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes, saluted. Forward, he ordered. Forward.

Stonewall Jackson watched the tide roll on.

Had he known what lay ahead for him and for his men—but for him, specifically, and him most of all—Jackson would surely have still gone forward. He believed in an “ever-kind Providence” that would call him home when it was his time. He believed in his mission. He believed in his duty. He was, in his later words, “perfectly resigned.”

Behind Rodes, stacked like a fist, Raleigh Colston’s division lined up to await its chance to move forward, too. Behind Colston, A. P. Hill’s division approached, bringing up the rear of the marching column, sliding into place as Jackson’s reserves.

Behind Hill: thirteen miles of dusty road, trampled and trammeled by twenty-eight thousand sets of feet, many of them bare, many of them footsore, all of them used to long, secret marches as members of “Jackson’s Foot Cavalry.” This was just another day at the office for these men, except that it was Saturday, and these men had work to do.

Back along that road, back past the intersection where the farm lane merged with the Brock Road, the intersection where Fitz Lee met Jackson with a reconnaissance report that ultimately changed the column’s route of march, sending the men north toward the Turnpike where they would turn east and assemble. Jackson paused at that intersection long enough to write to Lee: “I hope as soon as practicable to attack,” he scribbled, trusting in the “ever-kind Providence” to “bless us with success.”

Back. Back along that farm road, lined today by earthworks from the battle of the Wilderness. Back past houses and hidden lakes and hilltop farms. Back past Poplar Run, the only splash of refreshment for these men on a hot, dusty day, with temperatures in the mid-80s, with men falling out of column from heat stroke, if only they had the chance to pause, to drink, to refresh. Splash on through. Fifty-six-thousand feet churn the water, and even that is welcome relief.

Back. Back along that farm road, lined today by earthworks from the battle of the Wilderness. Back past houses and hidden lakes and hilltop farms. Back past Poplar Run, the only splash of refreshment for these men on a hot, dusty day, with temperatures in the mid-80s, with men falling out of column from heat stroke, if only they had the chance to pause, to drink, to refresh. Splash on through. Fifty-six-thousand feet churn the water, and even that is welcome relief.

Back along the road through dark, thick forest—the dark, close wood—one of the waste places of nature. Short, thick trees crowd the edges, dense with underbrush, fighting for light, all alive with green, with green. Alive. Alive and close. So close. Whiplash oaks and scraggly pines. Wild roses and holly. Vines and creepers. And somewhere, hovering over those desolate woods, an “evil genius of the South,” says one Confederate later.

Backwards, away from the trickle stream, over camel humps in the terrain, the road ascends a long hill and curves eastward toward Brock Road. On Brock Road backwards, northwards—northwards where, if such a turn had been taken earlier, the route would risk exposing the men to prying Federal eyes posted along Herdon Road. And so, not northward but, after a few hundred yards on Brock Road, eastward again, back, back, back.

Back through woods. Back past a clearcut today that has left a blighted, stump-studded landscape, ash-gray, littered with dead branches and wood chips and strips of bark. Here, too, the evil genius of the South has struck, in modern times, to raze the very landscape itself.

Had Jackson’s men marched back, they would not have passed a horse farm with blanketed roans grazing quietly, pastured among a blanket of green and not among the riot-forest of green kept out by the pasture fence. Instead, they would have passed white tails leaping into the brush, signaling danger then disappearing. Grouse. Turkeys. Fox. A bear. Wild game. For some, lunch.

Back past the Wellford farmstead, with four women and Charles, Senior, and Charles, Junior—junior whose father had “voluntold” him to serve as a guide and lead Jackson’s men along this road. Back past an unfinished railroad cut, where Jackson’s men walk by, unconcerned, unknowing that the men defending their rear, the 23rd Georgia, would come to grief in this railroad cut. Would anyone stay to help them if they knew the Georgians’ fate? Who would go back? And who might see this railroad cut again, in other battles along different stretches and in different times, during Mine Run and the Wilderness?

Backwards, backwards, back past the Wellford’s iron furnace—Catharine’s Furnace—and back across Lewis Run and up out of the Lewis Run valley. Back past the break in the trees that allowed Federal gunners to see the Confederate column pass. The jig was up, the secrecy lost.

Back past a path that leads to the “brick house,” as labeled on the maps, but which served as the landlocked birthplace to the man who would become the father of oceanography.

Back. Back. Back. Back.

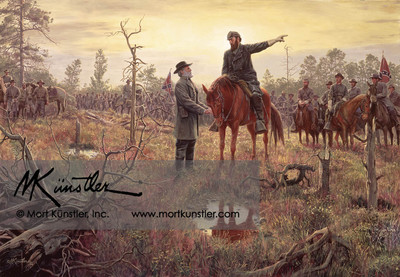

Back to where Jackson met his commander, Robert E. Lee, earlier that very day. Their last meeting. Un-overheard, they speak. Jackson points down the road. Forward. They will go forward. They may go forward then. Down the road, across the battlefield, into history, into legend, into myth. Memory becomes distorted.

Back to where Jackson met his commander, Robert E. Lee, earlier that very day. Their last meeting. Un-overheard, they speak. Jackson points down the road. Forward. They will go forward. They may go forward then. Down the road, across the battlefield, into history, into legend, into myth. Memory becomes distorted.

But we remember the march. We remember the attack. We, too, go back, go back. But we, too, may go forward then.

Jackson thought he was on the flank of the Union Army, until advised otherwise. When Federal dispositions west of Chancellorsville forced Stonewall Jackson to abandon his original plan of advancing east along the Orange Plank Road on May 2, 1863, he led most of his corps north to a new point of attack on the Orange Turnpike.

Upon arriving at the Burton farm, Jackson realized that they had more marching to do to get on the flank the Union Army.

The site of the Burton farm, on the Chancellorsville Battlefield is owned by the NPS. There is a small cut off, large enough for one car, so you can stop and enter the woos and locate the foundation the home.

It is one of the sites of the Civil Warmwhere a momentous decision was made.

I’ve been there.

Very nicely done, a fresh approach – a rewind of the old story

And there stood that pious, priggish, elitist Protestant snob, O.O. Howard, like an inflexible stone wall.

Damn Damn Damn ,

Some 1 Stopped Printing & Captivating My Attn. in a Wonderful Story. I was in the Woods in my mind .! ???? Please I Need More. Thank You

Thanks Chris….awesome writing. I felt as though I was there!

May I introduce my friend Chris Mackowski, writer and historian–

Setting the stage, an almost lyrical prologue. Well done, Sir!