“Good-bye Again, Darling Annie”: The Short Marriage of Colonel and Mrs. Robert Gould Shaw

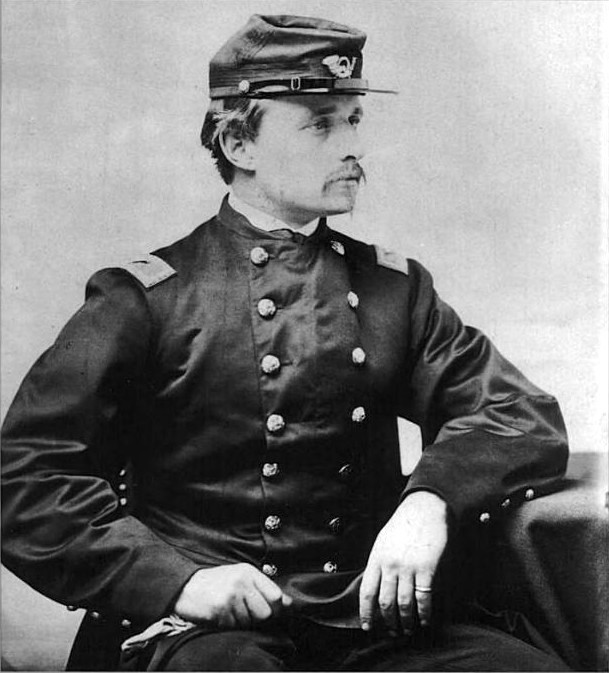

The battle of Chancellorsville raged in central Virginia on May 2, 1863, but in New York City’s Protestant Episcopal Church of the Ascension, it was wedding time. Twenty-five-year-old Colonel Robert Gould Shaw of the newly recruited 54th Massachusetts married his sweetheart, Annie Haggerty. The couple knew it was only a matter of time before he would be ordered to take his regiment into a campaign and battle.

Robert had consulted with his fiancée regarding his choice to take command of the 54th Massachusetts, the first African American regiment officially raised in the north after the Emancipation Proclamation. On February 4, 1863, he wrote: “please tell me, without reserve, what you think about it; for I am very anxious to know. I should have decided much sooner than I did, if I had known before.”[i] The thought of ending his volunteer military service after three years was regularly tempting, and he referenced it multiple times in his letters; taking the colonelcy of a new regiment meant a longer commitment. A telegraphed message with Annie’s support helped to finalize his choice to take the offered command.[ii]

For two years, Annie Haggerty had been a significant part of Robert Shaw’s life. In 1861, he met her at a party his older sister Susanna hosted and told a friend that “she would be my ‘young woman’ some time.”[iii] Annie came from a wealthy Massachusetts family, her father making his wealth through a prominent auction house in New York City. During the summer of 1861 after he had departed for war with the 2nd Massachusetts Regiment, Robert casually asked Susanna to send him Annie’s photograph, but insisted that “of course I don’t want you to get it from her.”[iv] He made special efforts to reply to Mrs. Haggerty’s letters, knowing that “Annie conducts all her mother’s correspondence, – doesn’t she?” (emphasis original).[v]

Eventually, Robert and Annie started corresponding directly, and in November 1862, he proposed marriage in a letter. On November 21, he revealed, “I have received Annie’s answer at last. She didn’t say ‘Yes,’ outright, but it was enough to repay me for writing, and for the two weeks of anxious suspense. I feel, after reading her note, that it will come all right in the end.” The young couple kept their engagement secret from all except their parents and Robert’s matchmaker sister, Susanna. The secret may have been from Annie’s preference for privacy and also because Robert had decisions to make about his military service.

The difficulties of organizing, training, and fulfilling the political and social demands to represent the 54th Massachusetts wore at Robert, and he turned to his relationship for comfort and stability. “Do write to me often, Annie dear, for I need a word occasionally from those whom I love, to keep up my courage. Whatever you write about, your letters always make me feel well; and I have enough discouraging work before me to make me feel gloomy.”[vi]

The gloominess and a sense of foreboding seem to have been driving factors in Robert’s desire to get married before his regiment departed. It took some convincing of both the Shaw and Haggerty parents, but eventually they agreed to a short engagement and quick wedding. In one of his persuasive letters to his mother, Robert explained that he did not intend to take Annie on a campaign with him, but “one reason for my wishing to be married is, that we are going to undertake a very dangerous piece of work, and I feel that there are more chances than ever of my not getting back. I know I should go away more happy and contented if we were married.”[vii]

The majority of Annie’s letters do not exist and she asked Robert to destroy her letters, but she seems to have been willing to marry before he returned to war. “Annie wants us to go to New York and be married in church, and very privately,” Robert reported on April 8, 1863.[viii] He also gave acquiescence to her preferences (which aligned with his) that he would not be married in uniform since it attracted too much attention.[ix]

Following their wedding on May 2, Colonel and Mrs. Shaw retreated to her family’s estate in Lenox, Massachusetts, for their honeymoon, where Robert wrote to a younger sister that he was “in quite an angelic mood…and haven’t felt envious of any one. Excuse this short note, for I am dreadfully busy” and then cataloged a very empty schedule with no visitors, no excursions, little reading, but “our own ideas are more interesting to us.”[x] The couple’s happy solitude ended abruptly when Robert received a message that Governor of Massachusetts ordered the 54th to depart from Boston for the military front at the end of the month.

Heading to the Carolinas by steamer, Robert wrote to Annie on June 1, “hoping we can live over those days at Lenox once more.” He kept her informed of their journey and his military hopes and some of his fears. “Until then, good bye, darling Annie. I hope you have recovered your spirits, got over your cold, and are feeling happy. Remember all your promises to me; go to bed early, and take as much exercise as you can, without getting fatigued…. Your ever loving Husband.” In the following weeks, Robert wrote detailed letters to his wife, explaining his difficult choices regarding plundering and “barbarous warfare” and trusting her to keep his military secrets and thoughts.

Quiet moments bothered him because there was too much time to “think and think, until I am pretty home-sick.” He wondered about the future: “Shall we ever have a home of our own, do you suppose? I can’t help looking forward to that time, though I should not; for when there is so much for every man in the country to do, we ought hardly to long for ease and comfort.”[xi]

Surviving letters to Annie do not indicate that he told her about his premonition for a battlefield death, but he may have been living with that idea for a long time. Certainly the dark idea was on his mind during the summer. Shortly before the 54th’s fatal assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863, Robert told one of his officers, “If I could only live a few weeks longer with my wife, and be at home a little while, I might die happy, but it cannot be. I do not believe I will live through our next fight.”[xii]

That day Annie Shaw—a wife for barely 2 ½ months—became a widow. Her husband’s body was never returned, instead buried by enemy hands in the trench with his fallen Black soldiers. While Robert’s parents accepted and lionized their son’s abolitionist martyr status, Annie kept silent and moved deeper into invisibility in history and memory. Given her constant desire for quiet and privacy, her choice was not necessarily surprising. Her relationship was hers, and she chose not to make her widowhood a public symbol. Annie Shaw did not remarry, living until 1907 and residing in Europe for most of her life. A few post-war letters between Annie and her sister-in-law, Josephine Shaw Lowell survive.

Robert Shaw’s romance, relationship, and marriage is not acknowledged or portrayed in the 1989 film Glory. Perhaps, there is a level of appropriateness to this choice. Adding a romance element would have detracted from the strong plot and focus of the film. Also, it seems perhaps most respectful to Annie’s desire for privacy during her lifetime to not splash a version of her story across Hollywood’s screens.

Still, her choice to marry and her strength cannot be underestimated. A few weeks after Robert Shaw’s death, Dr. Lincoln A. Stone, a surgeon of the 54th Massachusetts, wrote to Annie:

“I wanted to express in some way, to have you understand, how deeply we feel your husband’s death, and that you have our sympathy in your hour of grief. Every day adds to the great loss we have had, and we miss the controlling and really leading person in the regiment; for he was indeed the head, — brave, careful, just, conscientious, and thoughtful. He had won the respect and affection of his men, and they all had great pride in him and his gallantry. Many a poor fellow fell dead or mortally wounded in following him even into the very fort, where he fell; glad thus to show their affection, or unwilling to seem backward or afraid to follow their dear, brave Colonel even to death.”[xiii]

While Stone’s letter is from a military perspective, perhaps his words echo Annie’s own decisions. She had not followed her husband to a battlefield literally, but by marrying in May 1863 when they knew his regiment would depart soon, she showed her own affection. She was unwilling to turn back from a life with him…or the risk of life without him. In some ways, she followed him to death, and from the letters he wrote to her, she evidently had “great pride in him and his gallantry.”

In life and in memory, Annie Haggerty Shaw has remained the strong shadow behind Robert Gould Shaw. His mother and sisters were part of his life and pushed him toward the great causes they championed, but Annie was his confidant, almost his secret. She represented his hopes for the future and his reasons to live. The different stages of their lives together can almost be summarized by one of the closings in his final letter to her, “Good bye again, darling Annie.”

Sources:

Berkshire Eagle, “Gould and Two Women of Lenox,” 2007. https://www.berkshireeagle.com/archives/gould-and-two-women-of-lenox/article_63f3d093-0d71-596b-97fb-93a4e9eee7fe.html

Find A Grave, Anna Kneeland Shaw: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/11055934/anna-kneeland-shaw

Shaw Letters: https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/24/resources/1892

[i] Robert Gould Shaw, edited by Russell Duncan, Blue-eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1999). Page 283.

[ii] Ibid., page 285.

[iii] Ibid., page 292.

[iv] Ibid., page 128.

[v] Ibid., page 150.

[vi] Ibid., page 289.

[vii] Ibid., page 317.

[viii] Ibid., page 322.

[ix] Ibid., page 323.

[x] Ibid., page 328.

[xi] Ibid, page 360.

[xii] Memorial R.G.S (Boston: Cambridge University Press, 1864). Accessed through Archive.org: https://archive.org/details/memorialrgsrober00cambuoft/page/136/mode/2up Page 166.

[xiii] Ibid., page 136.

A superb article. Bravo!

Thank you for this well written article. My father Francis G. Shaw and my brother, Robert Gould Shaw were family descendants of the Colonel.