Comparing US and CS Service Branch Antebellum Experience

Every now and then, historians go down a rabbit-hole, spending hours diving into some obscure subject or collecting information, statistics, or examples of whatever draws them in. Just such a thing happened to me recently regarding US and Confederate military and naval leadership statistics, with some interesting results.

The United States Civil War is largely remembered as a conflict where volunteers (and draftees) with no prior military experience took up arms to fight. Both armies in the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861 were “green alike” after all.[1] However it was also considered the first West Pointer’s war, as it was the first conflict where large numbers of West Point trained officers served in major leadership positions. It was also the first major conflict following the establishment of the US Naval Academy.

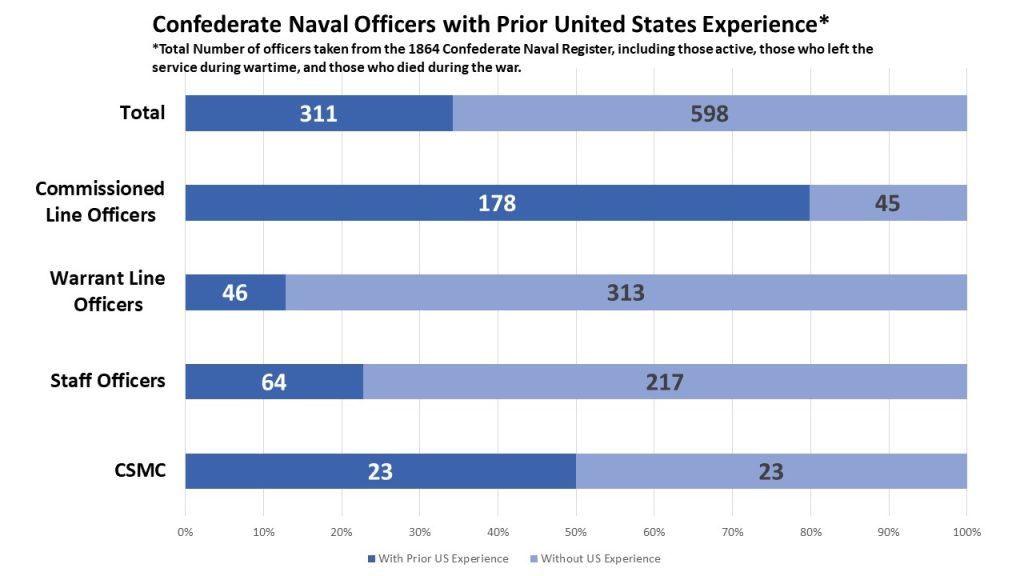

So, to the rabbit-hole. Last year I published an article in US Military History Review titled “Postwar Identity Crisis of the Confederate Navy’s Officer Corps.”[2] Part of that examination was compiling how many of the Confederate Navy’s officers had antebellum US government experience, which would thus make them exempt from receiving amnesty from President Andrew Johnson at the end of the war. The compiled statistics were quite surprising.

The Confederate Navy was a small organization, numbering 5,213 at its peak in 1864.[3] Less than 1,000 men served as officers in the CSN/CSMC throughout the war. Of those, approximately 35% held antebellum experience with the US Government. What is surprising about this statistical compilation is the CSN’s commissioned line officers. Of those officers, lieutenants and above who were eligible for command at sea positions, 80% held antebellum US Government experience! Thus, the rabbit-hole. Were these numbers comparable to other major leadership positions in the CSA, USN, and USA?

Before continuing, I need to explain what I mean by antebellum US Government experience. In compiling these statistics for all branches on both sides. I counted such service as attendance or graduation from either West Point or the US Naval Academy, active service in the USA/USN/USMC/US Coast Survey/US Revenue Marine before the Civil War, or active militia service where their militia organization was mobilized for national service. In compiling these statistics, I did not include those who were simply drilling members of a state militia that never activated for national service until after Fort Sumter’s bombardment. I also did not count anyone who graduated from a state or local military academy before the Civil War who did not enter active US service at some point. I also excluded those with military or naval experience abroad in foreign services (except for the Republic of Texas, which joined and became incorporated into US services).

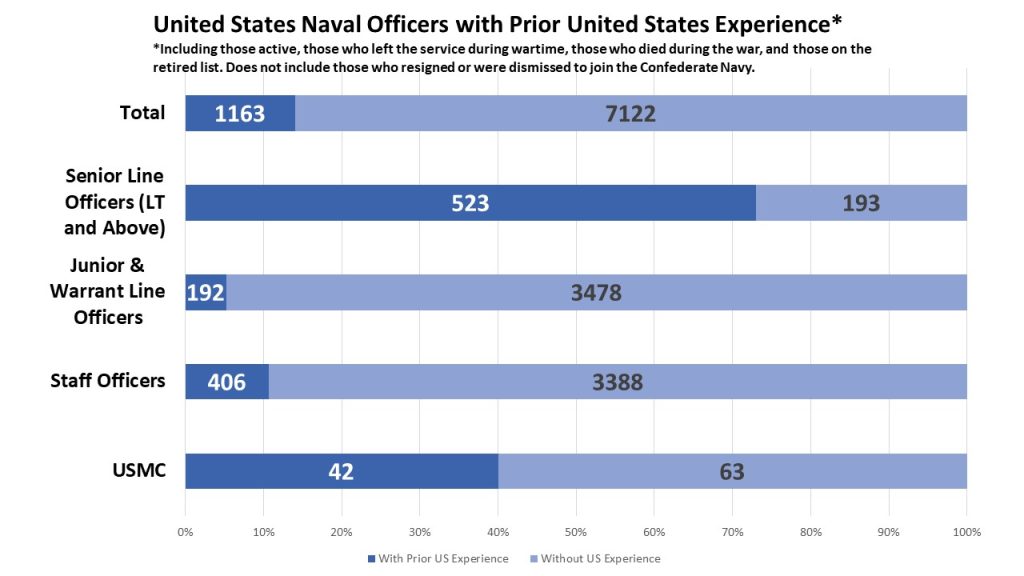

Now for the comparison. The easiest point of comparison is with the USN. To do that, I combed through the USN registers from the war, compiling and listing every single commissioned and warrant officer with wartime service (excluding those who resigned or were dismissed from the USN at the start of the conflict). The results resembled those of the CSN. Staff, junior, and warrant officers had a relatively low rate of professional antebellum experience, but of senior line officers ranked lieutenant and above (those most eligible to command warships at sea), 73% held antebellum US Government experience. The lower percentage for warrant and staff officers also makes sense for both the USN and CSN. The lower junior and warrant officer groups include all of the midshipmen from both sides’ naval academies, which were packed with teenagers who could not have held antebellum service. Staff officers including doctors, lawyers, paymasters, and engineers all held skills more transferrable from civilian jobs. Thus, many of these positions in ever-expanding navies would have been filled with civilians brought into their respective navies.

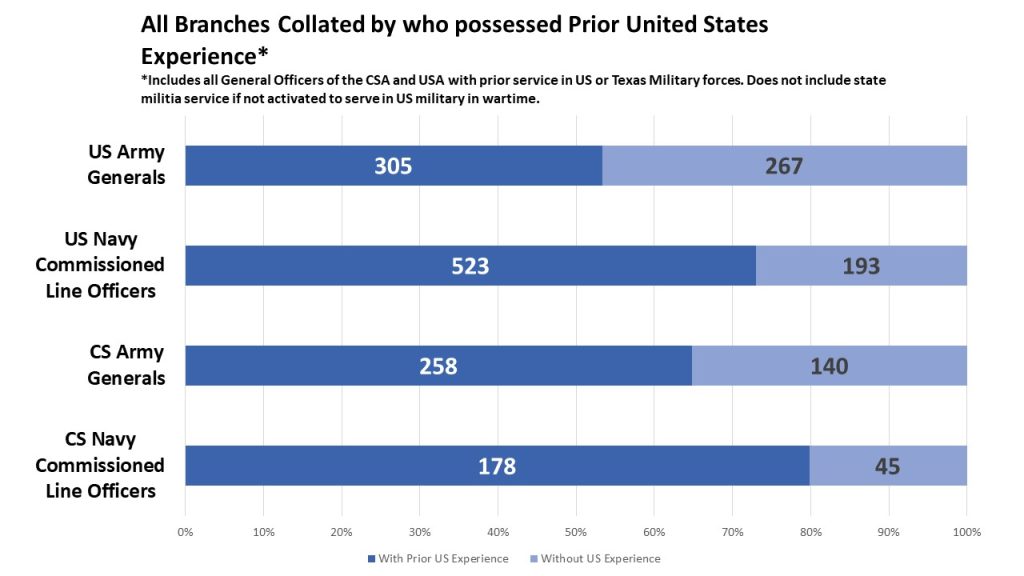

Comparing these statistics to army forces is daunting, as those service branches were much more massive on both sides. For a more reasonable comparison, I chose to compare the USN/CSN statistics to those of USA/CSA general officers. Another note of compilation though, as there are debates and questions over who was a general and who was not. I excluded all brevet promotions to general from the war (including the massive system of those promotions that took effect as of March 1865). I also excluded generals who were never officially nominated or confirmed by their respective legislatures or who died before being confirmed. Nonetheless, when referring to these statistics of generals, I recognize that there will be some discrepancies in the numbers overall.

After compiling and tabulating, I concluded that approximately 65% of CSA generals had prior US Government experience. This is a lower figure than the prior experience threshold of both navies’ commissioned line officers, but it is still a relatively impressive percentage. For the US Army, I tabulated that approximately 53% of US wartime generals held antebellum US Government experience.

Again, I did make many exclusions that lowered the percentages for general officers. If you include those with foreign service (Patrick Cleburne for instance), then the percentages go up. If you include those with antebellum militia service who did not do anything while a member of that militia, the percentage goes up higher.

So, what conclusions can be drawn from these overall statistics? It is clear the naval branches held a cadre of more experienced senior line officers on both sides, but this logically makes sense. Commanding a ship required a significant amount of technical prowess, understanding of engineering principles, knowledge of seamanship, in addition to the expertise in small arms, gunnery, and manpower management needed for managing land forces. Both the United States and Confederate naval services took volunteers as officers, but those generally held antebellum experience on merchant ships to gain such expertise and entered the service at a relatively low rank.

The smaller the organization, the larger percentage of its senior officers held antebellum US Government experience. This makes sense, as smaller organizations were more able to leverage their experienced officers into more leadership positions at lower levels of command. Conversely, the much larger US Army held the smallest percentage of senior leaders with antebellum US Government service, though logically that also makes sense considering the millions of volunteers inducted into the US Army in the conflict. As the war continued, volunteer officers slowly gained the needed experience to keep the US Army operating.

Something else worth mentioning though is that there seems to be an inverse in success compared to antebellum experience. The US Army and Navy won the war but held a lower percentage of its senior officers with antebellum experience. While this alone cannot be a single factor for US victory or Confederate defeat, it does raise many interesting follow up questions about Civil War leadership overall.

One final takeaway is that an army general could typically rely on the fact that a wartime warship captain likely had some sort of antebellum experience. Those generals who were willing to work with these naval professionals likely found more success, even if it was sometimes a high-ranking general working with a lower naval lieutenant. For me, I just thought that the overall statistics were interesting and worth sharing, especially being a Navy man myself.

Endnotes:

[1] “Historians’ Forum: The First Battle of Bull Run,” Civil War History, Vol. 57, No. 2, June 2011, 111.

[2] Neil P. Chatelain, “Postwar Identity Crisis of the Confederate Navy’s Officer Corps,” U.S. Military History Review, Vol. 8, No. 1, Fall 2022, 18-50.

[3] John K. Mitchell to Stephen Mallory, April 28, 1864, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 2, Volume 2 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1896), 640.

You should write a book of biographical sketches of Civil War naval officers… at least for the Confederacy. It appears you’ve done a lot of the research already.

At the start of the war the CSN had more antebellum ex-USN officers than they had naval slots available for them. That’s why many ex-naval officers served as army (usually artillery) officers. BGs Page and Higgins, Cols. James L. Henderson, Charles H. McBlair, Fred Brand and T. W. Daviess, and Capt. W. W. Carnes come to mind.

Bruce, you are completely correct. Many CSN officers were advised to join the army because there were no ships for them to man in early 1861. Others, like Page, resigned from the CSN in the middle of the war and joined the CSA. Still others held dual-commissions in both the CSA/CSN. I will add it to my list to write a future blog posting about those cases and how it worked holding rank in both branches simultaneously. Interestingly, the USA also had a handful of generals that were former members of the USN who resigned from that service before the war.

Concerning the Engineer and Constructor Corps, the only pre-war “officers” were Chief Engineers. Lower ranked engineers were Warrants. (USN) Constructors didn’t become Warrant Officers until 1863. Of course, most US experience was with small paddle steamers so there was a reservoir of civilian engineer talent to draw from. I guess the requirements for that class of vessel would be more easily met than for example, the 1854 six screw-frigate program (which produced Merrimack). That class would also see the perfection of the massive pivot shell gun as opposed to the traditional broadside gun, though I guess there wasn’t a perceived need for an Ordnance Corps yet in the navy.