Ready and Able to Serve: The “Invalid Corps” in the Civil War

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Tonya McQuade…

Recently, while researching my great-great-great grandfather James Calaway Hale’s experience during the Civil War, I discovered an interesting fact: after getting sick in Helena, Arkansas, during his service with the 33rd Missouri Infantry, then recovering for a month at the Benton Barracks General Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, he was officially transferred to the Invalid Corps in July 1863. Previously, I thought that the nearly two years worth of letters he wrote from the Marine Hospital, another hospital at Benton Barracks, meant he remained too sick for two years to rejoin his regiment and resume performing his military duties. In reality, as new records I acquired showed, he had a new military assignment.

James was transferred on July 29, 1863, to the 13th Company, 2nd Battalion, of the Invalid Corps, which was created in April 1863 “to make suitable use in a military or semi-military capacity of soldiers who had been rendered unfit for active field service on account of wounds or disease contracted in line of duty, but who were still fit for garrison or other light duty, and were, in the opinion of their commanding officers, meritorious and deserving.” [1] By the end of the war, more than 60,000 men served in this Corps, in more than twenty-four regiments of troops.

The Corps was part of a larger effort to address the Union’s difficulties in filling the ranks of its enormous armies. President Abraham Lincoln had taken an important first step in January 1863 when he called for the enlistment of African American soldiers in his Emancipation Proclamation. Congress soon followed in March with its Conscription Act, the first draft in United States history. Then, as a third measure, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton authorized the creation of the Invalid Corps on April 28, 1863.

Corps members included men who had lost limbs or eyes, suffered from rheumatism (as did James) or epilepsy, were experiencing other chronic illnesses or diseases, or were traumatized by what we now call PTSD. Soldiers were, by this time, in short supply – and wounded and ill soldiers who previously would have likely been granted a medical discharge were needed to serve guard duty, do supply runs, escort and watch over prisoners of war, assist with clerical work, march in parades, and help with cooking and cleaning – thus freeing up other able-bodied soldiers for the front lines.

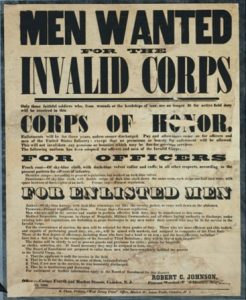

According to a poster seeking men to join the Invalid Corps: “Only those faithful soldiers who, from wounds or the hardships of war, are no longer fit for active field duty will be received in this Corps of Honor. Enlistments will be for three years, unless sooner discharged. Pay and allowances same as for officers and men of the United States infantry; except that no premiums or bounties for enlistment will be allowed. This will not invalidate any pensions or bounties which may be due for previous services.” [2]

The poster also describes the uniforms adopted for both officers and enlisted men in the corps. James would have been issued a “jacket, of sky-blue kersey, with dark-blue trimmings, cut like the cavalry jacket, to come well down on the shoulders. Trowsers, present regulation of sky-blue. Forage Cap, present regulation.” Those who were “most efficient and able-bodied” were armed with muskets and placed in the First Battalion. Those, like James, “of the next degree of efficiency, including those who have lost a hand, or an arm; and the least effective, including those who have lost a foot or a leg,” were armed with swords and placed in the Second or Third Battalion.

As a member of this new corps, James began staying in a house near “The Marine,” a shortened name for the Marine Hospital. The hospital – built between 1852-1855 with $100,000 in federal funds and originally intended for navy men, merchant marine, and river men – was converted during the Civil War to serve as a general military hospital for soldiers, both Federal and Confederate. [3] Heavy iron bars were placed on the windows of rooms housing Confederate prisoner-patients, whom the Invalid Corps helped to guard.

James was extremely impressed with The Marine, which he described in one of his letters as “almost the best building in the city,” heaping praise on its cleanliness and indoor plumbing. In his letters, he describes some of the jobs he was given, which included guard duty, sweeping, and helping with cooking.

The duties of the Invalid Corps were “chiefly to act as provost guards and garrisons for cities; guards for hospitals and other public buildings, and as clerks, orderlies, etc. If found necessary, they may be assigned to forts, etc.” [4] Its troops also “enforced the draft, guarded prisoners and vital outposts, protected rail lines and supply depots, and served as military police in cities all across the country. Members of the Corps escorted President Lincoln’s body home to Illinois, and after the war its officers formed the nucleus of the new Freedman’s Bureau.” [5]

In March 1864, the Invalid Corps was renamed the Veteran Reserve Corps. Partially, this was to boost morale as the same initials – “I.C.” – were used to stamp “Inspected-Condemned” on condemned property. Another important reason, however, was that many men in the corps – tired of being called “cripples” and “shirkers” – had complained about the negative connotation in the name. Their frustration was likely exacerbated by a song that became popular in 1863 titled “The Invalid Corps,” with lyrics as follows:

The Invalid Corps

By Frank Wilder

I wanted much to go to war,

And went to be examined;

The surgeon looked me o’er and o’er,

My back and chest he hammered.

Said he, “You’re not the man for me,

Your lungs are much affected,

And likewise both your eyes are cock’d,

And otherwise defected.”

CHORUS

So, now I’m with the Invalids,

And cannot go and fight, sir!

The doctor told me so, you know,

Of course it must be right, sir!

While I was there a host of chaps

For reasons were exempted,

Old “pursy”, he was laid aside,

To pass he had attempted.

The doctor said, “I do not like

Your corporosity, sir!

You’ll ‘breed a famine’ in the camp

Wherever you might be, sir!”

CHORUS

There came a fellow, mighty tall

A “knock-kneed overgrowner”,

The Doctor said, “I ain’t got time

To take and look you over.”

Next came along a little chap,

Who was ’bout two foot nothing,

The Doctor said, “You’d better go

And tell your marm you’re coming!”

CHORUS

Some had the ticerdolerreou,

Some what they call “brown critters”,

And some were “lank and lazy” too,

Some were too “fond of bitters”.

Some had “cork legs” and some “one eye”,

With backs deformed and crooked,

I’ll bet you’d laugh’d till you had cried,

To see how “cute” they looked. [6]

According to what I found online, “ticerdolerreou” is likely a reference to Tic Douloureux – a “severe, stabbing pain to one side of the face.” [7] At any rate, it’s easy to see why many might have found these lyrics offensive and why they changed the Corps’ name. A version of the song by the 2nd South Carolina String Band can be heard on Youtube…

The Veteran Reserve Corps celebrated their greatest success in July 1864 when Confederate Gen. Jubal Early arrived with an army of 15,000 at the gates of Washington, D.C. Almost every able-bodied Union soldier had gone south with Gen. Ulysses S. Grant as part of his campaign to take Petersburg, Virginia. Among the few left to defend the city – and the President – until additional Federal troops could arrive were clerks, government officials, and the Invalid Corps.

In the synopsis for her documentary film titled The Invalid Corps, which tells the story of the role these soldiers played in the Battle of Fort Stevens, filmmaker Day Al-Mohamed explains: “Made up of men injured in battle or by disease, these ‘hopeless cripples’ will hold out for a desperate 24 hours until Union General Grant can send reinforcements. With Abraham Lincoln himself on the ramparts of Fort Stevens, they cannot afford to fail. The story of the Invalid Corps offers a poignant perspective allowing us to reassess what we know, or rather what we think we know, about civil war history, disability, sacrifice, and honorable service.” [8]

Endnotes:

- Daley, Christopher J. “Veteran Reserve Corps.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veteran_Reserve_Corps.

- “Men wanted for the Invalid Corps.” New York Historical Society | Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nyhistory.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A159377.

- “Marine Villa’s Lost Marine Hospital.” St. Louis History Blog, https://stlouishistoryblog.com/2014/12/05/marine-villas-lost-marine-hospital/#fn1].

- “Men wanted for the Invalid Corps.” New York Historical Society | Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nyhistory.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A159377.

- “The Invalid Corp.” The Apothetae (ApoTheeTay), 10 November 2015, http://www.theapothetae.org/news/hot-cripple-11november-2015-the-invalid-corp.

- “The Invalid Corps.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Invalid_Corps.

- Khatri, Minesh. “Tic Douloureux Overview.” WebMD, 18 March 2021, https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/tic-douloureux.

- “Invalid Corps.” Day Al-Mohamed, https://www.dayalmohamed.com/invalid-corps.

- “US Military History You Should Know: Meet the Battle-Hardened Invalid Corps.” Cure Medical, https://curemedical.com/invalid-corps/

Tonya McQuade is an English Teacher at Los Gatos High School and lives in San Jose, California. She is a great lover of history, frequently visiting museums and historical sites with her husband and children, as well as reading and teaching historical texts, literature, and primary source documents. After acquiring 50 family Civil War letters in 2022, Tonya began researching the American Civil War in Missouri. She is currently working on a book incorporating the letters with historical commentary, titled A State Divided: The Civil War Letters of James Calaway Hale and Benjamin Petree of Andrew County, Missouri. Tonya earned B.A. degrees in English and Communication Studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and served there as a writer and editor for the student newspaper, the Daily Nexus, for four years. She also earned her Single Subject Teaching Credential in English at UCSB and later her M.A. in Educational Leadership from San Jose State University.

The patients in the military hospitals in Vermont (Brattleboro, Montpelier and Burlington) who became members of the Invalid Corps were used to guard the international boundary with Canada after the St. Albans Raid on October 19, 1864, by Confederate prisoners of war who escaped to Canada and crossed the border to rob the town’s banks and made an unsuccessful attempt to burn down the town.

Thanks for that additional example – I hadn’t read about their service on the border before.

Readers–If you like Meg and Sarah, you’ll LOVE Tonya! Huzzah for another great post on a very interesting topic.

Thanks, Meg! Hoping we can meet up sometime in June after the school year ends.

Many years ago, while processing new books in the NYU Library, a personal memoir of a Union infantryman crossed my desk. It had been discovered in a family attic in the early 1970s or so. I forget his name, state and regiment. The memoir was well written, spiced with charming watercolor sketches. He served on the barrier islands off the Virginia coast and was later wounded in the leg at the Wilderness. After recuperating, he was in the Invalid Corps, oops, Veteran Reserve Corps, acting as military police in Washington DC. One story started with him and his buddy patrolling into what the editor identified as the red-light district in DC. The next page was neatly cut out with a razor and with it, the rest of that story. Apparently, he decided to censor himself after writing it. Too bad.

An interesting example of another way the corps members served. Several of the letters I have from my GGG-Grandfather have squares cut out of them, making it impossible to read certain parts. I’m not sure if that was the result of later self-censorship or actual censorship during the war.

Great research (and writing) about much overlooked part of our miltary. Many of the soldiers involved with th assassination trial as well as the hanging of the conspirators were members of the I. R. or V. R. C.. They were needed, also. Thank you.

Excellent article about real heroes.