The Most Overlooked Fighting of the Most Overlooked Phase of the Overland Campaign

If the battle along the North Anna is the most overlooked phase of the Overland Campaign, then the action of May 25-26 is the most overlooked fighting of the most overlooked phase of the Overland Campaign.

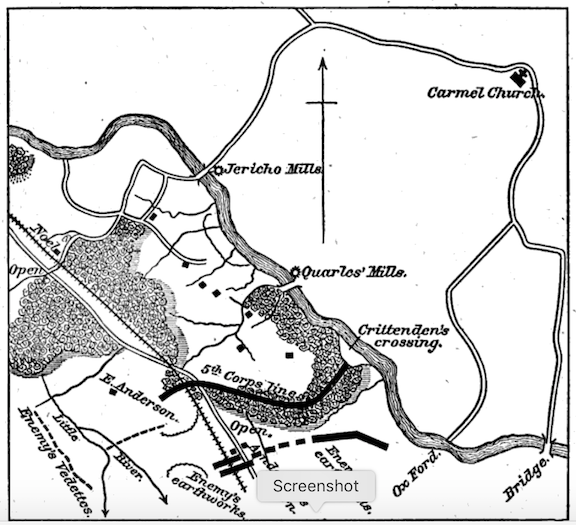

During the afternoon of May 24, Brig. Gen. James Ledlie led a botched assault—against orders—against the tip of the Confederate spear guarding the heights overlooking Ox Ford on the south bank of the North Anna. The dark clouds opened and, amidst the flash of lighting, Brig. Gen. “Little Billy” Mahone’s men easily repulsed the attack. Ledlie’s six shocked regiments tumbled back the way they’d come, followed closely by a Confederate counterattack. Ledlie’s men finally found safety with the V Corps division of Maj. Gen. Samuel Crawford. Mahone’s men, discovering resistant instead of retreating Yankees, settled into a rain-soaked skirmish but not push farther.

Crawford was in position, removed from the rest of the V Corps, because Warren had sent him eastward early on the 24th to help with the effort to clear Ox Ford. Bogged down by a mid-morning encounter with some of Mahone’s men, Crawford’s men had dug in, creating a fortified position that offered plenty of protection atop a rise, with the river guarding their back. That river posed problems of its own, though. The torrential rain of the 24th caused a quick rise in water levels that cut Crawford off from any reinforcements on the north bank.

By that point, Ledlie’s division commander, Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden, had finally moved the rest of his IX Corps division across the river. Ledlie’s had been the first brigade across, and Crittenden had ordered Ledlie not to attack the Confederate line because the rest of the division was, at that time, still trying to get across the river. Ledlie disobeyed that order and, as Crittenden crossed, Ledlie led his brigade to disaster.

As night fell over the battlefield on May 24, Crawford and Crittenden improved their position. Meanwhile, Crawford sent back to V Corps commander Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Warren for help, three miles to the west at Noel’s Station. The messengers actually reached the line of the VI corps, and commander Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright sent two brigades—those of William H. Penrose and Henry L. Eustis—on a nighttime relief mission.

By the morning of May 25, Warren moved the rest of his corps eastward, with Wright securing Warren’s right flank. Wright, in turn, protected his own right flank using the Little River to his south. In this way, the two corps advanced to try and get a better idea of the shape of the Confederate line. They eventually got their answer when they ran into A. P. Hill’s Third Corps, which made up the west-facing leg of a large inverted “V,” with Mahone’s men at the northern tip of the spear at Ox Ford.

“We drove them back near to their works,” said a member of the 155th Pennsylvania. “We remained on the line all days, and it was a terribly hot skirmish line. If anyone exposed himself to their view for a moment, almost instantly the balls would be whistling around thick.”[1]

With the rest of the V Corps on the scene, Crawford’s division came out from behind its ridgetop fortifications and linked up with the rest of the corps. Crittenden’s men stayed on the ridgetop and filled in the link between the V Corps and the river. As the lone IX Corps division on the south bank of the river on the west side of Lee’s inverted “V,” Crittenden received an order to temporarily report to Warren instead of Burnside. “He was quite offended at being ordered to report to his junior [in rank], Warren,” an observer noted, “but he was very pleasant and did not visit his dissatisfaction on W[arren].”[2]

Warren conducted a personal reconnaissance to better gauge the enemy position. “All along my front there is an open space between our skirmishers,” he reported to Meade. Confederates had cleared open fields of fire he estimated at three-quarters of a mile wide, and their skirmishers hid “behind logs and trees.” He also noted, “Sharpshooters are very active.” By the end of his inspection, he concluded, “I feel satisfied that I should have great difficulty at best in whipping the enemy in my front.”[3]

Warren’s pronouncement sounded more than a little like his conclusion the previous November at Mine Run, where he inspected the Confederate line and opted not to attack. There, his decision prevented a needless effusion of blood. So far in the Overland Campaign, though, Warren had shown a similar hesitancy to pitch in to battle, which had put him on U.S. Grant’s watch list. Fortunately for Warren, Meade’s trusted staffer, Theodore Lyman, accompanied him on the inspection and so could vouch for Warren’s conclusion. “They were skirmishing very hotly in the front,” Lyman attested.[4]

Federals tried to find a way around both Confederate flanks to no avail. On the western leg of the “V,” the Little River posed a minimal obstacle—but it was enough. Federals posted artillery on their own flank along a loop in the river to try and enfilade the Confederate line, but that provided little benefit. “[Charles] Griffin, as usual, was greatly excited and enthusiastic about putting some batteries which would enfilade this, that and the other!” Lyman noted.[5]

As the 25th rolled over to the 26th, men rotated in and out of the line. Some even took the chance to bathe in the river—their first opportunity since the start of the campaign. “Skirmishing continued and so did the rain,” the Pennsylvanian said; “it rained hard and we had a very disagreeable place to lie.”[6]

Rufus Dawes, commanding the 6th Wisconsin of the famed Iron Brigade—which had a rough day on May 23 at Jericho’s Mill in the opening fight of the North Anna phase—described the intensity of the harassing fire. “The bullets clip through the green leaves over my head as I lie behind the breastworks writing . . .” he told her. “I have not composure to write, as the bullets are coming so quickly through the limbs. . . .”[7]

By morning, the “hot firing” had slowed to ten to twelve shots a minute, Dawes said, but “the rain storm had become violent.”[8] Along the eastern leg of the inverted “V,” both sides likewise settled into a slow, sniping stalemate.

Somewhere near army headquarters, Lyman noted the presence of a female Confederate POW in the custody of the provost marshal. “She was an artillery driver,” he said, “and had on a common, gray soldier jacket, and a U.S. forage cap. Her hair was long and fell on her shoulders. She seemed a common woman, but not wanting in decent modesty, and said she had enlisted because her only brother had gone. She asked not to be mixed with the prisoners in going to Washington.”[9]

Part of Wright’s corps spent May 26 engaged in destroying a long stretch of the Virginia Central Railroad, which stretched westward toward Gordonsville and Staunton, beyond. “We tore up and destroyed all we could of bridges, culverts, etc., and got fresh hog,” one soldier crowed.[10]

But even as they worked, the VI Corps maintained a tight grip on the Little River, which foiled attempts by Confederate cavalry commander Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton at finding a way around the Federal flank. Lee had lost his chance to “strike them a blow” on May 24, but he still looked for some way to exploit the Federal army’s split formation: the V and VI Corps (and Crittenden’s IX Corps division) still on the west side of Lee’s inverted “V” and the IX and II corps on the east side. Lee would look in vain.

Meanwhile, Grant ordered the Army of the Potomac to maintain its position and prepare, secretly, for a withdrawal that night. With no way around the Confederate flanks, and no viable chance at a successful frontal assault, Grant decided to once more go around Lee’s army. Using his newly returned cavalry, which had been absent from the army since May 9, Grant faked a movement to the west and once more slipped around the Confederate right flank to the east.

“In the evening we received marching orders,” said the member of the 155th Pennsylvania. “We started through the rain, mud, and darkness; any one of the three would have been uncomfortable, but the three combined, and such Egyptian darkness as that was, reminded us of the first night of our Gettysburg campaign. We crossed the river on pontoons and in the next four hours marched four miles.”[11]

Grant would continue moving “On to Richmond” once more, taking with him exactly the wrong lesson from his time along the river. He came to the belief that Lee’s army was too weak and demoralized to fight effectively, and based on that flawed premise, he believed he needed to land just one more solid blow of his own in order to knock Lee’s army out of the fight. That erroneous conclusion would lead to a hard lesson just a few days later at Cold Harbor.

————

[1] D. P. Marshall, Company “K,” 155th Pennsylvania Volunteer Zouaves: A Detailed History of Its Organization and Service to the Country… (1888), 164.

[2] Theodore Lyman, Meade’s Army: The Private Notebooks of Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman, David W. Lowe, ed. (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2007), 174

[3] Warren to Meade, O.R. XXXVI, Pt. 3, 191, 192, 193.

[4] Theodore Lyman, 174.

[5] Lyman 174.

[6] Marshall, 165.

[7] Rufus Dawes, Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (E.R. Alderman & Sons, 1890), 277.

[8] Dawes, 277-8.

[9] Lyman, 176.

[10] John Hartwell, To My Beloved Wife and Boy at Home: The Letters and Diaries of Orderly Sergeant John F.L. Hartwell, Anne Hartwell Britton and Thomas J. Reed, eds. (Vancouver: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997), 232.

[11] Marshall, 165.

Very well written as usual,Chris, particularly about Grant learning the wrong lesson. His legendary stubbornness could degenerate into blindness.

Agreed, well to include that Grant learned the wrong lesson from North Anna. From the article, it seems Grant never realized the danger Meade’s army was in, that he pulled it back because there wasn’t a chance to advance. I baselessly thought Grant realized that he was in an unsprung bear trap and that was why he pulled back and, getting away clean, suspected that the Rebs were so weak they couldn’t exploit such an advantageous position.

I thought Warren was aggressive earlier in May at Laurel Hill, somewhat against Meade’s desires, but the point of the paragraph is that Meade was keeping an eye on the guy.

Interesting article. Thank you.