When Does the Peninsula Campaign End?

When does the Peninsula Campaign end?

When does the Peninsula Campaign end?

Earlier this month, I had the chance to interview Dough Crenshaw and Drew Gruber about their new ECW Series title To Hell or Richmond: The 1862 Peninsula Campaign for the Emerging Civil War Podcast. During our conversation, this question came up, which I thought was an especially thought-provoking one.

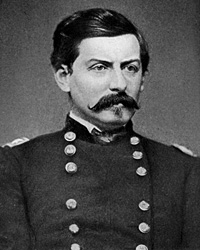

The actions we tend to associate with “The Peninsula Campaign” on the James Peninsula in Virginia began in March 1862 when Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan landed his 120-thousand-man army at Fort Monroe. In early April, began marching northwest toward the Confederate capital in Richmond. With several actions along the way, including confrontations at Yorktown and Williamsburg, Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston slowly gave ground as McClellan advanced.

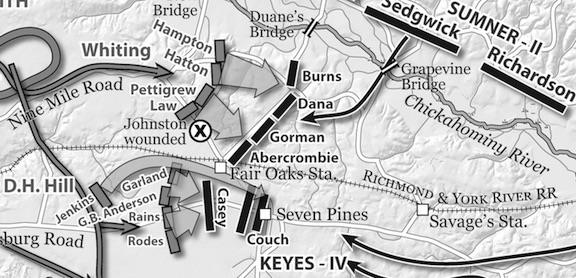

Then, of course, came the battle of Fair Oaks/Seven Pines on May 31–June 1. Johnston sustained a pair of injuries that not only knocked him out of the fight but also knocked him out of the leadership of what then became the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed Gen. Robert E. Lee to command the army, which is now seen by many as a major turning point of the war.

After strengthening the fortifications around Richmond, Lee launched a series of attacks on June 25, 1862, that became known as the Seven Days’ Battles. The first, at Beaver Dam Creek, began the proves of driving McClellan away from the gates of Richmond. They concluded on July 1, 1862, at Malvern Hill. McClellan’s army hunkered along the banks of the James River under the protection of Union gunboats until he received an order from Washington on August 4 to withdraw from the Peninsula.

Historically, we tend to divide the actions with the change in Confederate command. So, everything from McClellan’s arrival on the Peninsula through the battle of Seven Pines is “The Peninsula Campaign.” We might also throw in those weeks of waiting that follow as McClellan brought up his siege guns.

But during that time, Lee began to draw up his plans for command, so that period might also be included with the Seven Days. They serve as the prelude for the fighting.

The Seven Days’ Battles themselves are pretty clear-cut: Beaver Dam Creek, Gaines’s Mill, Savage’s Station, White Oak Swamp, Glendale, and Malvern Hill. McClellan’s “change of base” to Harrison’s Landing on the James, and his long time sitting there, serves as the postscript to the fighting.

And he sits there for a long time.

My ECW colleague Mike Block argues—convincingly, I think—that the battle of Cedar Mountain on August 9 is actually the final battle of the Seven Days’ campaign.

But it’s that historically neat-and-tidy change in command that most often serves as the dividing line between Peninsula and Seven Days. But as Doug and Drew and I spoke, it occurred to me that the dividing line is only a dividing line from a Confederate perspective.

From a Federal perspective, McClellan is still maneuvering on the peninsula. He has marched to Richmond, won several engagements, knocked out a Confederate commander, and are awaiting the change to continue the offensive once the guns are in place—and then, pow!, Lee socks the Federals on the nose.

The Federals reel, they move, they shift, they retreat, they fight, they win—there’s a fluidity that feels like the culmination of events, not necessarily a discrete set of events themselves.

So maybe, we wondered as we thought out loud, perhaps the Peninsula Campaign doesn’t end at Seven Pines. Perhaps it goes all the way until August, depending on who’s perspective you consider.

Of course Lee’s almost always wins out because he’s been so idolized in the last 161 years, while McClellan has become one of those generals almost all of us love to mock. But those views have evolved with the benefit of historical hindsight. We know how events turned out. In the summer of 1862, participants were still living through events. Did anything feel discrete and neat and tidy?

When we consider the Peninsula Campaign, whose perspective do we take and why? And how does that help—and hinder—our understanding of those events?

————

List to the podcast episode here.

To Hell or Richmond: The 1862 Peninsula Campaign is available now from Savas Beatie here.

The companion volume, Richmond Shall Not Be Given Up: The Seven Days Battles, is available from Savas Beatie here.

I think the campaign ends on August 3, when Henry Halleck orders McClellan to abandon Harrison’s Landing and proceed with his army to a new line on Aquia Creek. Only then does McClellan have to face the fact that his effort – such as it was – is over. It is thus for the time being exit McClellan, enter John Pope.

I tend to agree with Kevin. I always assumed that the Penimsula Campaign ended when McClellen began moving troops from Harrison’s Landing back towards Washington.

Chris makes excellent points and raises some interesting questions regarding the end of the Peninsula Campaign. It depends on your perspective, and definition of ‘Peninsula Campaign.’

For Joe Johnson, the campaign ends with his wounding. Does it begin for Robert E. Lee after Seven Pines, now as the overall commander before Richmond? Or should his actions the previous months be considered? Lee dispatched Jackson to confront the Federal armies in the Valley as a method to keep them away from Richmond. Is the Valley Campaign part of the Peninsula Campaign?

From a Confederate strategic perspective, the campaigns on the Peninsula, the Valley, before Richmond and at Cedar Mountain are all part of the same fight. The overall success of each (and they must succeed) ensures Richmond remains the Confederate Capital. That was their objective.

Did the Federal armies have an overall national strategy or even an operational strategy in Virginia during the spring and summer of 1862. Other than successfully occupying the Confederate capital? No.

For many, the Peninsula Campaign ends when the Army of the Potomac is firmly ensconced at Harrison’s Landing July 2, 1862. It’s the end of the Seven Days. But fighting continued. Not on the scale of the previously displaced, but men still died.

Robert E. Lee was dealing with a lot militarily (politically as well, but that’s for another day). He was concerned that a restart of fighting would take place. Numerically, MG George McClellan’s army was still a potent force. Lee was aware that the divisions of MG Ambrose Burnside and MG Isaac Stevens were sailing north to points unknown. Lee did not want them to reinforce McClellan. He absolutely did not want them disembarking at Bermuda Hundred or City Point. Traveling up to Aquia Landing and marching south was not ideal either. Then there was John Pope.

MG John Pope’s 42,000 man Army of Virginia was stretched along today’s modern Route 211, from Warrenton to Sperryville. Whenever Pope moved south, Lee had to react to the new threat, wherever they marched.

Fortunately for Lee, Burnside and Stevens paused briefly at Fort Monroe before continuing north, Pope’s army did not move until early August and George McClellan sat at Harrison’s Landing lamenting the lack of manpower.

McClellan’s messages to Washington during this period continued his pattern established long before the campaign began. He needs more men. He wants Burnside and Stevens assimilated into his army. He want Pope’s army to join him as well. McClellan also continues to recommend national policy to the President.

Finally ordered away from Harrison’s Landing on August 3, McClellan dawdled until mid-August before embarking his men or marching them back down the Peninsula. McClellan’s Peninsula campaign ended.

When the direct threat from McClellan ended after Malvern Hill and his removal to Harrison’s Landing, Lee dispatched MG Thomas J. Jackson and his Army of the Shenandoah, first to Louisa Court House, then to Gordonsville to protect the key railroad junction in that town on July 13. His orders to Jackson, in a nutshell, were to keep Pope out of Gordonsville and thereby away from the western approaches to Richmond, but be prepared to quickly return to Richmond, as the situation warranted. Lee did not want a two front fight in front of Richmond — he needed Jackson to keep Pope away.

Stonewall successfully fulfilled his mission, blunting Popes advance at the Battle of Cedar Mountain on August 9. Understanding that he had only defeated one of Pope’s three corps, and was numerically inferior to Pope, Jackson wisely withdrew back across the Rapidan two days later, to continue his primary mission of protecting Gordonsville.

On August 13, four days after the action at Cedar Mountain, Lee realized that McClellan was no longer a threat to Richmond and dispatched MG James Longstreet to Louisa in preparation of confronting Pope’s army. Lee followed on August 15. The Peninsula Campaign, or as the Lee and the Confederate government might have named it, the Defense of Richmond, was now over.

For Robert E. Lee, John Pope and George McClellan, what we call the Second Manassas (or is it Bull Run?) Campaign had begun.

As I said, convincingly argued! Well done. 🙂

Good points all. To me, the Peninsula ends when Lee takes charge, because Union strategic momentum, which had been almost inert under the Wonder Boy, shifted to the Confederates. Wonder Boy’s response to the hard fight at Gaines Mill demonstrates how hard he was looking for an excuse to skeedaddle. To me the Seven Days Campaign needs a better naming, because it really doesn’t end until Le Petit Napoleon gets well nestled into Harrison’s Landing.

There’s an interregnum between campaigns

Pope’s initial forward movements seem to me to be the beginning of the Second Manassas Campaign.

“Wonder Boy”–ha! 🙂

I join Kevin and Stan. McClellan was still at Harrison’s Landing and was confronted by Lee (although Lee had started to shed troops in late July). Not to oversimplify but that’s still the “Peninsula” and that was two large forces still facing each other on the Peninsula – until they weren’t.