Milliken’s Bend and Kirby Smith’s Grand Strategic Blunder

While Nathaniel Banks enveloped and attacked Port Hudson, Richard Taylor reformed his forces after their ordeal in Bayou Teche. With Kirby Smith’s permission, he began an offensive meant to aid Port Hudson and hopefully lift the siege. In late May he chased the Federals, from Opelousas to Brashear City. It was a hollow victory. The Rebels failed to capture the Federal wagon train or inflict heavy losses. The region was devastated and the locals, even Confederates, had lost hope. Unionist and particularly neutralist sentiment grew and there was open resistance to conscription.

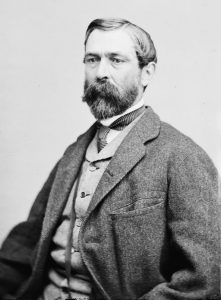

Taylor next planned to strike into the Lafourche, sweeping aside Banks’ garrisons and marching on New Orleans. Cavalry and infantry were on the way from throughout the Trans-Mississippi, in particular John G. Walker’s Texas division. Walker was not West Point trained, but he served in the army as an officer until July 1861. He fought in Virginia, playing a key role in the capture of Harper’s Ferry. He was promoted and sent to Arkansas, where he trained twelve raw Texas regiments. His men had yet to see battle, but had a reputation for being well drilled.

Before Taylor could strike, John C. Pemberton asked Smith for aid. He wanted Federal supply points on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi River destroyed, thinking it might save Vicksburg. It was a desperate request and Ulysses Grant had clearly shifted his main supply base to the east side of the Mississippi River. Regardless, Smith ordered Taylor to send Walker’s division to clear the area out and if possible cross over. Taylor would face a motley collection of raw regiments, mostly made up of black troops guarding supply depots and government run plantations.

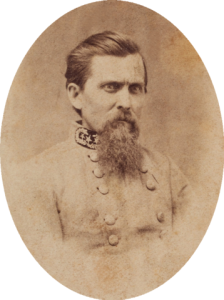

By May 30, Taylor was in position but he had to repair a bridge at the Tensas River and wait for the 15th Louisiana Cavalry Battalion, which were to act as guides. Meanwhile, on May 31 Henry E. McCulloch surprised the 60th Indiana at Perkins Landing. He drove the Federals to the river, but the ironclad U.S.S. Carondelet arrived. McCulloch had to back off. All the operation accomplished was giving Grant warning that his Louisiana garrisons were under threat. Grant reacted by sending an infantry brigade and replacing the sluggish Jeremiah C. Sullivan with Elias Dennis.

The 15th Louisiana Cavalry Battalion knew the area and were led by Isaac F. Harrison, a determined man who did not shrink from violence. In 1861 he killed one of his slaves who was planning a revolt. On June 4, Harrison surprised a camp of instruction at Lake St. Joseph. The men hauled in prisoners, all of them escaped slaves. On June 6 Harrison bloodied a Federal probe aimed at Richmond. Taylor, not an easy man to impress, beamed “I do not think he has a superior in the service.” Harrison indicated that along the river the Federals had only meager forces. By now it was clear there was no great haul of prisoners or supplies to be had. Taylor might have given up, but he was determined to at least fulfill his orders. To do this as fast as possible, Taylor planned a three pronged attack at Young’s Point, Milliken’s Bend, and Lake Providence. With any luck he could then hurry south to oversee the attack on New Orleans, the operation he thought had an actual chance at victory.

Harrison was wrong about Young’s Point. It was being used as a transportation hub and was strongly garrisoned by veteran regiments. On June 7, James M. Hawes struck Young’s Point but was delayed due to a damaged bridge at Walnut Bayou. By the time he arrived, Federal reinforcements were at hand and there were gunboats in support. Hawes retreated, having accomplished nothing, save losing 200 men, mostly due to the heat. The Lake Providence attack produced no results.

Hermann Lieb was at Milliken’s Bend with the the 9th, 11th, and 13th Louisiana and 1st Mississippi. Only the 9th Louisiana had proper drilling. The other regiments consisted of untrained men, some only days removed from slavery. In addition, they were using cast-off weapons. Fortunately, Lieb was reinforced by elements of the 23rd Iowa, which had seen combat. The brigade numbered over 1,100 men and held a lightly fortified position.

McCulloch struck at dawn with around 1,500 men. The Confederates were enraged because they had fight former slaves. Yet, today it seemed the anger was directed more at the officers. The common cry was “No quarter for the officers, kill the damned abolitionists, spare the niggers.” The Union troops fired a strong volley that sent many Texans fleeing for the rear. Still on they came. H.H. Miller of the 9th Louisiana wrote “The enemy charged us so close that we fought with our bayonets hand to hand. I have six broken bayonets to show how bravely my men fought.” Such was the fighting in places the blood was inches deep.

The Confederates, better armed, trained, and led, were successful. Much of the 23rd Iowa, only recently arrived and not fully formed, broke while the officers of the 1st Mississippi fled their command. The 9th Louisiana stood for a time, as did pockets from other black regiments. McCulloch remarked that while the “negro portion” fought “with considerable obstinacy” the “white or true Yankee portion ran like whipped curs. McCulloch exaggerated. Elements of the 23rd Iowa fought on, with one whole company apparently killed and wounded to the man.

The Union force fell back to the river bank, where the 23rd Iowa and 9th Louisiana reformed. About that time Union timberclads U.S.S. Choctaw and Lexington appeared and McCulloch fell back. Only the fire of warships prevented the total destruction of Lieb’s brigade.

Milliken’s Bend was a short but savage engagement. The Rebels lost 175-185 men. The Union lost around 500, although some reports inflated the number to as high as 652. The 23rd Iowa brought 120 men and lost 65. The 9th Louisiana, which kept itself together for most of the fight, suffered 60% casualties. The 11th Louisiana lost around 40% of its 482 men. Union officer losses were particularly high, a testament to the Texans resolve to kill men they saw as John Brown in uniform. Lieb carried a bullet in his hip until he died in 1908.

Almost immediately there were rumors of a massacre. However, it seems unlikely, although certainly some were murdered. At least one cluster of dead black soldiers were found on the battlefield, each shot in the head. One reason Milliken’s Bend was not a massacre is because McCulloch and Taylor forbade the killing of prisoners, which drew Smith’s ire. He thought such leniency would only encourage runaways and recruitment. From then on the policy in Smith’s department was no quarter, a position Walker fully approved.

Taylor’s operations in northeast Louisiana sputtered on after the June 7 attacks. On June 9, Frank Bartlett with the 13th Texas Mounted Infantry and the 13th Louisiana Cavalry Battalion struck Lake Providence. His mission was to break up camps of instruction for freedmen and the plantations the Federals had authorized. The post though was held by Hugh T. Reid, who had the 16th Wisconsin, 1st Kansas Mounted Infantry, and the 8th Louisiana. Reid and the 16th Wisconsin were veterans of Shiloh. Bartlett managed to ambush a supply wagon, but he found Reid too strongly posted along the Tensas Bayou.

Taylor blamed his subordinates and to a lesser degree the men themselves for the dismal results. He had both Hawes and McCulloch transferred. Having satisfied his orders, and eager to hit New Orleans, Taylor headed south. Walker remained until Grant sent an 8,000 man force led by Joseph Mower. In the weeks ahead Richmond was razed to the ground. The town was never rebuilt.

Walker withdrew to Delhi and remained there until June 22, when he gamely struck out again. On June 29 William Parsons, leading Texas cavalry, raided near Goodrich Landing. Plantations were torched and 2,000 blacks were seized and re-enslaved. At Mound Plantation, Parsons encountered companies E and G of the 1st Arkansas (African Descent). The regiment was decently armed and drilled, but with around 128 men, the outpost was doomed. The white officers negotiated with the Confederates and betrayed their men. They ensured their own safe treatment, but not those of the soldiers they led, who were treated brutally. By June 30 much of the countryside was aflame. Some burned buildings housed charred human remains and others were found on the roadside. Nearly all were likely freedmen.

Joseph Johnston accused Smith of doing nothing to save Vicksburg, so Smith personally arrived to command Walker’s division, doubling down on a failed strategy. He wanted to plant batteries, drive cattle into Vicksburg, and send infantry to the doomed city. It did not matter. On July 4, Pemberton surrendered. Walker withdrew on July 11, having received tardy orders to head to Taylor’s aid. By now his division was demoralized and diminished by sickness. The campaign’s last act came on July 14, when the 14th Wisconsin landed at Vidalia and captured Smith’s main supply train. With that the northeast Louisiana offensive was over and the Confederates had little to show for their efforts in a strategic backwater. Walker’s division was wasted on pointless attacks which accomplished nothing of value.

Navy to the rescue!