The Surrender of Port Hudson

After the failure of his second assault on Port Hudson, on June 15 Banks called on a “Forlorn Hope” of choice volunteers. They would storm the Rebel lines, lured by promises of recognition, promotion, and medals made from captured Confederate guns. Banks wanted 1,000 men. 1,300 stepped forth, mostly from regiments that had not seen heavy action on May 27 or June 14. The men of the regiments that had participated in the previous attacks were incredulous. Lawrence Van Alstyne of the 128th New York thought “it must be a joke.” By contrast, almost the entire 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards volunteered, although only around 150 were accepted.

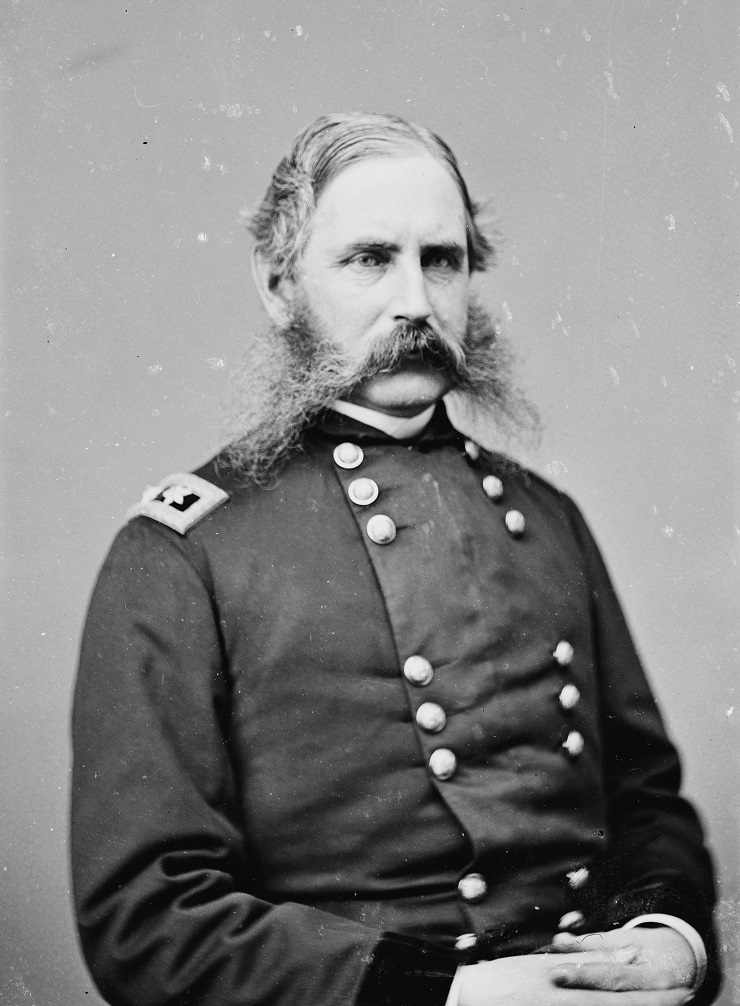

Henry Birge volunteered to command the “Forlorn Hope” and brought with him 241 men from the 13th Connecticut, their only request being they did not wish to attack on a Sunday. Morale was high in this unit and the training in rapid assault was sound. Meanwhile, trenches were built near the Priest Cap and Fort Desperate. Once the trenches were finished, both positions were to be stormed by Birge’s men.

As July approached, supplies of all kinds in Port Hudson were nearing exhaustion. Ammunition was so low that the Rebels picked up spent bullets. By the end of June, the last cow had been slaughtered and the men were issued mule and dog rations. Franklin Gardner resorted to eating broiled rats.

Gardner hoped that either Taylor would take New Orleans, Joseph Johnston would come down with a relief column, or that Banks would attack again. Gardner had men dressed in blue uniform infiltrate the lines. He knew Banks was in bad shape and that he planned to storm the lines. He hoped that after Banks failed in his third assault, a counterattack could be made in order to escape. Gardner’s plan centered on surprise, but his sentries failed to figure out the countersign not knowing that XIX corps was not even using one.

Gardner’s hopes were not unfounded. The XIX Corps was in poor shape. The 173rd New York openly declared they would not go into battle under Banks. The nine month men were convinced they were being used up to preserve the three year troops, who in turn blamed the nine month regiments for the failed attack on June 14. Christopher Augur said of the nine month 48th Massachusetts “I wouldn’t give a damn for twenty-thousand of such soldiers.”

To compound matters, Banks’ rear was threatened by John Logan. On June 15, the 41st Massachusetts Mounted Infantry and 14th New York Cavalry were routed. Hundreds were taken prisoner. On June 20, Logan captured sixty wagons and scattered the 2nd Rhode Island Cavalry. On July 1 Logan’s men captured Neal Dow, who was recovering at Heath Plantation from his May 27 wound.

Logan struck Banks’ supply depot at Springfield Landing on July 2. Logan’s riders trampled the 162nd New York and rode in throwing flaming turpentine firebombs. Union losses were nearly 200; Logan lost fourteen men. Some drowned as they fled into the river to escape the flames and the Confederates. In the lines at Port Hudson, panic reigned. Many fled and an entire regiment was sent to Banks’ headquarters, lest he suffer Dow’s fate. Combined with Thomas Green’s efforts along the Mississippi River, Banks’ supply lines were becoming strained.

Worse than Logan’s raids, sunstroke and disease knocked out 4-5,000 of Banks’ men, particularly after June 14. With labor short, thousands of freedmen were put to work in the trenches. It was punishing work, done without pay and under fire. Both sides launched probes and raids in the coming weeks. The Confederates even used flaming arrows to destroy cotton bales the Federals used for cover.

The combination of heavy losses, heat, bickering officers, and the successes of Logan meant that Banks was in a precarious position. As such, he wanted to keep the nine month troops until Port Hudson surrendered. Henry Halleck supported Banks, telling him he should fire cannon on mutinous men and “You will be sustained in any measure you may deem necessary to enforce discipline.” When the 40th Massachusetts refused to serve past their term, Banks had them disarmed, their flag seized, and many of the officers stripped of rank. Men in the 48th Massachusetts were also arrested. When the 50th Massachusetts threatened to go home, Banks threatened them with death or imprisonment in the infamous Dry Tortugas. Nathan Dudley, one of Banks’ brigade commanders, managed to keep them in line by saying “For God’s sake boys, don’t rebel and make fools of yourselves, as a certain regiment has, and disgrace the old Bay State. Brace up; Port Hudson can’t hold out long.”

On July 3 Birge, Cuvier Grover, and Godfrey Weitzel visited the Priest Cap. It was decided to attack on July 4. However, a Confederate countermine destroyed a tunnel, which the Federals hoped to pack with explosives. Banks decided to strike on July 7. The plan was for Augur and William Dwight to make feints meant to draw men away from the northern sector. Birge’s Forlorn Hope and some of the Native Guards would then attack the Priest Cap.

On July 6, Gardner’s men and Dwight’s command noticed debris, the carcasses of animals, and cotton bales floating down the Mississippi River. On July 7, Thomas Kilby Smith of Grant’s staff brought Banks the news that Vicksburg had fallen. The XIX Corps was exalted. Bands played, men cheered and taunted the Confederates. A one hundred gun salute was ordered up. Gardner that same day spoke with his officers. By then Johnston had confirmed he was not coming.

Gardner decided that Banks had no need to attack again, and as such they should surrender. Interestingly, Banks was considering an attack for July 9, but Gardner’s message ended his hopes of taking Port Hudson by storm. After midnight a ceasefire was arranged. After receiving confirmation that Vicksburg had submitted, Gardner and Banks met to discuss capitulation on July 8. Gardner made sure the talks were long. He wanted any Confederates willing to escape to have a chance on the night of July 8. That night some of the garrison fled, although how many exactly is unknown. Many took to the swamps. Others floated down the river.

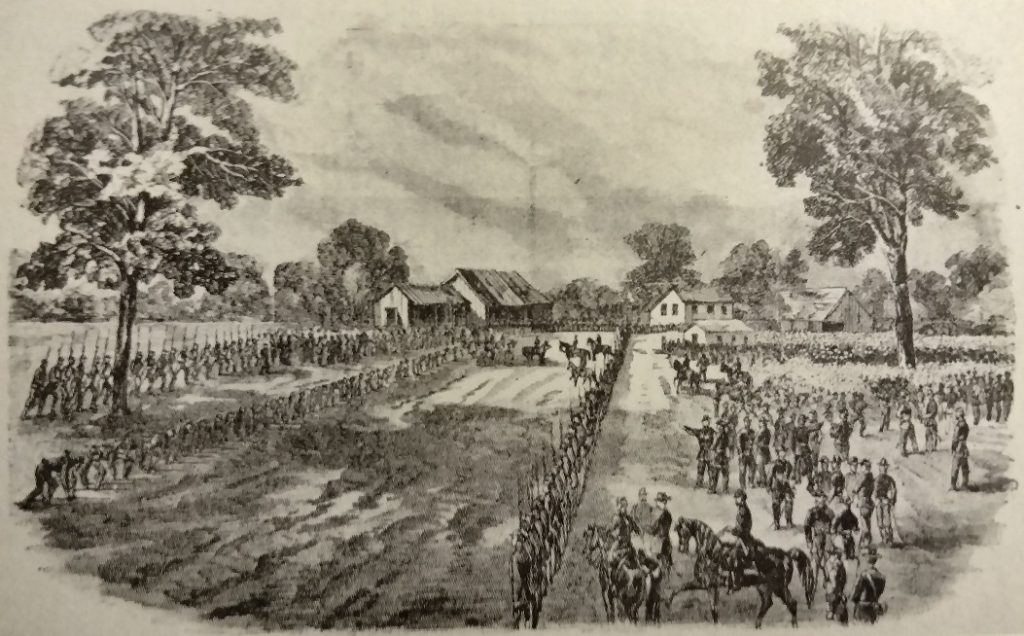

The next day, the 13th Connecticut struck up “Yankee Doodle” as Birge’s command was given the honor of marching into the fortifications. Gardner offered his sword to George Andrews, who was to be the post commander. Andrews gave it back, saying “I return your sword as a proper compliment to the gallant commander of such gallant troops –conduct that would be heroic in another cause.” Gardner took the sword, kissed the hilt, and replied “This is neither the time nor the place to discuss the cause.”

The Federals paid honors to Gardner’s command. The band, after playing the “Star Spangled banner” followed it with “Dixie.” Yet, some blacks yelled at the Confederates. Of Gardner’s command, only 3,000 were well enough to attend the ceremonies, but they were defiant. A common refrain was “They couldn’t take us by fighting! They had to starve us out!”

In total, Gardner surrendered 5,000 men, fifty-one cannon, and two steamers. He had lost 764, including 250 deserters. Banks’ losses were not properly reported, but likely lost 5-6,000, mostly in the two major assaults with another 4-5,000 down due to disease and sunstroke. Although not all died, it was far more than Gardner’s loss of 200 due to illness. Even worse, many of the nine-month men did not reenlist. XIX Corps was victorious, but at a heavy price.

Folks defending their homes invariably enjoy better morale at times like this, 90 degrees, high humidity, poor rations, sickness in camp, etc.

Tom