A Surprising Friendship Formed at Lone Jack: Union Major Emory Foster and Bushwhacker/Bank Robber Cole Younger

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Tonya McQuade…

Throughout the summer Union leaders grew increasingly concerned about guerrilla activity in the area, which had resulted in “growing numbers of soldiers shot out of their saddles, wounded, or disappeared while on patrol … [and had] so disrupted federal mail, communications, and travel that Union command in Jackson County was effectively isolated from the rest of the state.” [2] They were also aware that several Confederate leaders had come north from Arkansas to find new recruits – and their efforts were proving successful in many regions, especially in the northwest and along the western border.

In August 1862 two battles in Jackson County proved the bushwhackers’ ability to organize and inflict damage on Union troops. On August 11, under the leadership of Confederate Col. John T. Hughes and guerrilla leader William Clarke Quantrill, approximately 700 bushwhackers attacked the Union garrison at Independence. Hughes led the surprise pre-dawn attack that resulted in 14 Union soldiers killed, 18 wounded, and 213 missing or captured. [3] However, Hughes – a cousin to Gen. Sterling Price – was also killed in the fighting.

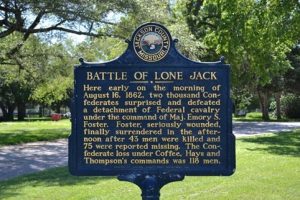

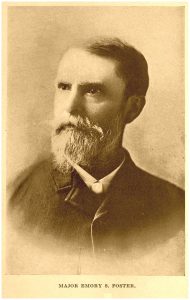

As part of a planned counterattack to remove the guerrilla menace from the border region, four days later, Major Emory Foster marched 800 Union soldiers from Lexington to Lone Jack, a small town near Kansas City, Missouri. The plan was for his troops to converge there with other Union troops marching from Clinton, Missouri, and Fort Scott, Kansas. Unfortunately, Foster and his men arrived days before the other troops. A skirmish the evening of August 15 between Foster’s forces and some rebels camped on the outskirts of town alerted enemy bushwhackers and new Confederate recruits in the surrounding area to their presence.

The following morning, 1,600 rebels attacked Foster’s troops. Fighting lasted for about five hours, and the town of Lone Jack was virtually destroyed. For a more detailed account of the battle, refer to the 2022 Emerging Civil War post by Kristen M. Trout, titled “Lone Jack – the Fight for Control of Northwest Missouri.”

Foster and his men, believing they were battling bushwhackers who had publicly avowed to give no quarter to captured Union troops, bravely kept fighting despite being outnumbered, preferring death in combat to surrender and execution. Foster himself was injured in the fighting, and his brother, Morris Foster, carried him from the battlefield, receiving a bullet through his right lung in the process. Foster was replaced on the field by Capt. Milton H. Brawner, who finally ordered a retreat. Only about 400 of Foster’s original troops returned to Lexington. The bushwhackers were victorious, but they were not able to maintain control of Lone Jack once the other Federal troops had arrived.

Jackson County was the home of William Clarke Quantrill – and of all the guerrilla leaders, many believed he was the most ruthless. It was likely fear of his presence that kept Foster and his men fighting in the battle of Lone Jack. Quantrill fought with Price’s army at the battles of Wilson’s Creek and Lexington, but he had since deserted and formed his own “army” of loyal men known as “Quantrill’s Raiders.” Among his men were William “Bloody Bill” Anderson, Frank and Jesse James, and Cole – and later Jim – Younger. Quantrill’s Raiders were responsible for numerous brutal attacks throughout both Missouri and Kansas. Despite this, he was elevated to the rank of captain by the Confederate government after his participation in the battle of Independence, and his raiders – considered outlaws by the U.S. government – were officially recognized as a troop by the Confederacy.

He and most of his men, however, were still in Independence at the time of the battle of Lone Jack, celebrating their victory and looting the surrounding area. Only 18-year-old Cole Younger was present in Lone Jack; and ironically, it was he who helped save the wounded Union Major Emory Foster and his injured brother from being executed by a drunk and vengeful Confederate bushwhacker. The two wounded men were hiding in a nearby cabin when they were threatened by their attacker, a personal enemy from before the war began, whom Foster later identified as Col. Josiah Hatcher Caldwell, a doctor from Warrensburg who had joined up with Price’s army back in 1861. [4]

As Foster described many years later, “In a moment [Younger] had seized the rowdy, disarmed him and knocked him headlong through a window. Then he stood guard over us. ‘My name is Cole Younger’ he said, ‘and I pledge my name for your security.’” Thinking they were mortally wounded, the two Foster brothers thanked Younger, then gave him $1,000 and their handguns and asked that he deliver them to their mother’s home in Warrensburg, about 26 miles away, which he did. [5]

Years later, Foster returned the favor. Younger, with his brothers Jim and Bob, had been captured in the James-Younger Gang robbery of First National Bank in Northfield, Minnesota in 1876 and sentenced to life in prison at Minnesota Territorial Prison in Stillwater. Foster, now a newspaper editor for the St. Louis Evening Journal, argued for clemency for Younger. [6] A letter he wrote in the late 1890’s helped Cole and his younger brother, Jim, to finally be paroled in 1901. Bob had died in prison of tuberculosis in 1889. Upon hearing the news, Foster wrote the following to Cole Younger on July 27, 1901:

I did not telegraph or write you my congratulations because I saw Capt. Bronaugh at my house the evening before he left for Minnesota and requested him, as he said he should be the first to see you, to give you my kindest regards and congratulations. You have a splendid friend in that indomitable man. It was through his initiative that I wrote the letter that I hope and believe helped you. However, don’t waste any time in expressing gratitude to me. How would it have ended with me at Lone Jack if you had not been there. I only regret that the parole was not a full pardon. I am entirely disabled from the wound I received at Lone Jack which reopened last September. I trust that you and your brother may succeed and be happy as long as you live.

Your friend, Emory Foster [7]

Foster died the following year in Oakland, California, where he moved in hopes of regaining his health. The “Capt. Bronaugh” he referred to was Warren Carter Bronaugh, a Confederate veteran who labored, along with Foster, to get the Younger brothers released and who wrote a book about his efforts, entitled The Youngers’ Fight for Freedom: A Southern Soldier’s Twenty Years’ Campaign to Open Northern Prison Doors.

Another Union soldier who fought at Lone Jack also credited Cole Younger with helping to save his life: Stephen Benton Elkins, who briefly taught school in Cass County, Missouri and went on to become U.S. Secretary of War between 1891-1893 under President Benjamin Harrison. He joined Foster and Bronaugh in arguing for Cole Younger’s parole.

Younger, as it turned out, had been a student of Elkins in Cass County. When Elkins was later captured by Quantrill’s gang, both Younger and Frank James recognized him. When they learned Quantrill had ordered that Elkins be “taken to the rear,” or executed, Younger and James convinced Elkins’ guards to let them take over responsibility for the prisoner. As later reported, “Cole Younger turned to Elkins and said: ‘About half a mile further we are going to come to the forks of the road. We will take the right hand. You put the spurs to your horse and take the left, or you are a dead man as sure as your name is Steve Elkins.’ Elkins needed no further encouragement. When the parting of the ways were reached he laid down flat upon his horse’s back and plunged the spurs in and got well out of danger before he was missed by anybody but the men who connived at his escape.” [8]

Years later, Younger wrote to Elkins from prison, seeking his help. Elkins had never forgotten how Younger helped save his life and tried many times to secure Cole and his brother’s pardon, even traveling to Minnesota on several occasions to intervene with the governor.

After his release from jail, Cole lived another fifteen years. Early on, he and Frank James, who was never convicted of any crime, staged the “Great Cole Younger and Frank James Historical Wild West Show.” Later, he wrote a memoir entitled The Story of Cole Younger: Being an Autobiography of the Missouri Guerrilla Captain and Outlaw … by Himself, worked as a tombstone salesman and production head of a railroad, successfully toured as a lecturer, and joined the Christian Church back in his birthplace of Lee’s Summit. There, he died in 1916 at the age of 72. [9]

Tonya McQuade is an English Teacher at Los Gatos High School and lives in San Jose, California. She is a great lover of history, frequently visiting museums and historical sites with her husband and children, as well as reading and teaching historical texts, literature, and primary source documents. After acquiring 50 family Civil War letters in 2022, Tonya began researching the American Civil War in Missouri. She is currently working on a book incorporating the letters with historical commentary, titled A State Divided: The Civil War Letters of James Calaway Hale and Benjamin Petree of Andrew County, Missouri. Tonya earned B.A. degrees in English and Communication Studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and served there as a writer and editor for the student newspaper, the Daily Nexus, for four years. She also earned her Single Subject Teaching Credential in English at UCSB and later her M.A. in Educational Leadership from San Jose State University.

Endnotes:

- Sanchez, Michael E. “Battle of Lone Jack Historical Marker.” The Historical Marker Database, 11 October 2019, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=140868.

- O’Bryan, Tony. “Battle of Lone Jack.” Civil War on the Western Border, https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/battle-lone-jack.

- “First Battle of Independence.” Civil War on the Western Border, https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/timeline/first-battle-independence.

- E. Foster, Esq. “Open Letter to Dr. Caldwell, Who Lately Came From Dixie.” August 8, 1865, St. Louis Globe Democrat, https://www.newspapers.com/image/571015997/?terms=E.%20Foster%20Letter%20to%20Dr.%20Caldwell&match=1&clipping_id=72310270.

- “Emory S. Foster – Lone Jack Historical Society.” Lone Jack Historical Society, https://historiclonejack.org/?page_id=470.

- Matthews, Matt and Lindberg, Kip, “Shot All to Pieces, the Battle of Lone Jack, Missouri, August 16, 1862,” North and South, Vol. 7, No. 1, January, 2004, page 66.

- “Emory Foster Letter to Cole Younger Dated July 27th, 1901.” quantrillsguerrillas.com, http://quantrillsguerrillas.com/en/articles/211-emory-foster-letter-to-cole-younger-dated-jul-27th-1901.html.

- “STEVE ELKINS A FRIEND – Senators Untiring Efforts for Youngers – Persistent Pleadings for Their Pardon.” Los Angeles Herald, Volume XXVIII, Number 239, 27 May 1901, https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH19010527.2.64&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN.

- Soodalter, Ron. “Life on the Run: Riding With the Younger Brothers.” Missouri Life Magazine, https://missourilife.com/younger-brothers/.

Fascinating aricle. Thanks. I wish to invite a fellow Californian to visit the Drum Barracks Civil War Museum in Wilmington, CA. The Museum is housed in the last remaining wooden structure of the Drum Barracks 60 acre base built around 1862. Civil War sites are few and far between here in the Golden State.

Thanks – I’ll have to check out the museum there sometime. Yes, not too many sites here in California, though I also recently learned about a Civil War Museum in Redlands that I want to visit. Maybe I can fit both of them into a visit soon!