Three Tigers and a Cheer: Remembering the Megster

A friend from the university sent me a music video the other day. “Do you know the band Alpha Rev?” he asked. “Thought of you when I was spinning this one.”

The song, “Lexington,” came from the band’s 2013 album Bloom. “Originally, I got the idea for this song when I found a letter from a Civil War soldier to this family, and he was saying how he didn’t think he was gonna live through this next battle . . .” explained songwriter Casey McPherson at the beginning of the video. “It really struck me how he knew that his days were about to be over. And I thought, What if I knew that? What if I knew my time was about to come, and what would I say to the people I love?”

I thought immediately of my friend Meg Groeling. Meg had been struggling with lymphoma since the spring of 2021. She seemed to be in remission, but for the previous month or two, she hadn’t been feeling so hot. She complained of being tired all the time. Early July saw her in and out of the hospital as doctors tried to pinpoint the cause—only to discover that her cancer had come back, aggressively, and had spread.

“I can’t help but think this might be my last time,” she told me on the phone last week. “Maybe I’ll bounce back. But I don’t think so.” Usually so full of irrepressible cheerfulness, my dear friend sounded tired. So very tired.

This conversation sat as the backdrop as I listened to songwriter Casey McPherson talk about “Lexington.” “It’s really easy for me to take my relationships for granted,” McPherson said. But his Civil War letter had made him realize: “Every time I leave the person I love, am I saying goodbye the way that I want to say goodbye to them?”

I started listening to the song, stripped down to a mournful piano and plaintive lyrics. “Oh, morning near, the flag is calling. . . .”

This is when I received the message from Meg’s husband, Robert: Meg had died shortly after 9:15 a.m. that morning.

“No,” I gasped. “No, no, no. . . .”

My six-year-old, Maxwell, ran over. Seeing my tears, he hugged me—then darted away, grabbed his blanky, and wrapped me in it. He held me as I cried.

* * *

At 9:15 a.m. Pacific Daylight Time, I had just started a presentation to the Chambersburg Civil War Seminar about the May 1863 battle of Jackson, Mississippi. Seminarians were in Vicksburg, where it was 11:15 a.m.; I was in Fredericksburg, Virginia, where it was 12:15 p.m.

The project that became my book on the battle of Jackson had, in an earlier iteration, originally been destined for ECW’s 10th Anniversary Series book The Summer of ’63: Vicksburg and Tullahoma. One of the delightful rabbit holes of that project led me to the story of Old Abe, the War Eagle. Old Abe seemed like the exact kind of story Meg would write about. After all, she had written “War Chicken” about Robert E. Lee’s pet poultry in the Gettysburg Campaign. She loved wacky human-interest stories, and she was a big animal lover, too.

I called her to see what she knew about Old Abe. She’d heard of him but didn’t know much about him. “Well, here’s your chance to learn,” I told her. I pitched the idea of co-writing a piece about Abe for the Vicksburg book.

Meg dove into the project with pinions aflutter and lots of glee. As we worked on the draft, she suggested a title that captured the sort of Victorian-era excess that characterized postwar biographies about the bird: “Old Abe, the Eighth Wisconsin War Eagle: A Short Account of his Exploits in War and Honorable—as Well as Useful—Career in Peace, with Emphasis on the Vicksburg Campaign.” The final result appeared as one of the original essays in The Summer of ’63: Vicksburg and Tullahoma. (My Jackson book grew to such an ungainly length that we cut it from that book and Ted Savas published it as a book of its own.)

Shortly after the book came out in the summer of ’22, a box marked “Fragile” arrived on my porch. Inside was a beautiful antique candy dish. The lid on such a lovely piece of glassware would normally be a ball-shaped knob that one could grab and lift. Instead of a knob, this dish cover had a frosted cut-glass eagle: Old Abe himself. The dish dated to 1883ish, created by the Crystal Glass Co. of Bridgeport, Ohio.

Shortly after the book came out in the summer of ’22, a box marked “Fragile” arrived on my porch. Inside was a beautiful antique candy dish. The lid on such a lovely piece of glassware would normally be a ball-shaped knob that one could grab and lift. Instead of a knob, this dish cover had a frosted cut-glass eagle: Old Abe himself. The dish dated to 1883ish, created by the Crystal Glass Co. of Bridgeport, Ohio.

“Meg, I can’t accept this!” I told her over the phone.

Meg pshawed me. “I’m old, and I can’t take my money with me when I go,” she said.

Meg loved to send gifts, particularly hand-made gifts of intricate detail. She found delight in the details of things. The individual craftsmanship reflected the uniqueness she felt each of her friends deserved. She would send hand-made Christmas cards and delicate hand-made paper ornaments. She found someone online who made Civil War-themed cockades, and Meg often commissioned customized designs as gifts.

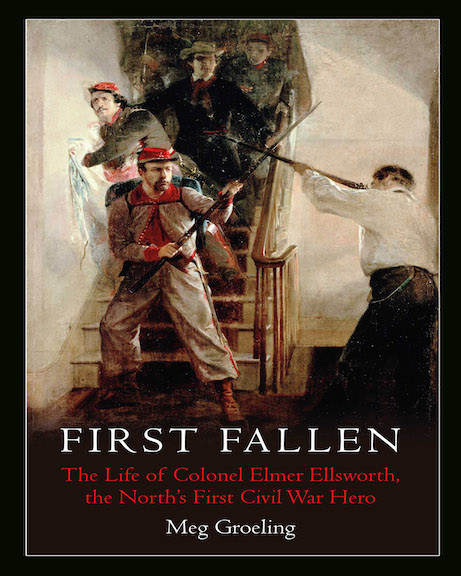

When Meg’s book First Fallen: The Life of Elmer Ellsworth, The North’s First Civil War Hero came out, she had little carte de visites of Ellsworth printed up with little reminders to “Remember Ellsworth!”—a Northern rallying cry early in the war that she adopted to keep alive the memory of her Civil War crush. She also loved to give people “Three tigers and a cheer” or, in response to an email with happy news, she might simply reply with a cookie emoji. She had such generosity of spirit, so eager to cheerlead for everyone, so glad to celebrate their successes. Everyone who did something good deserved a cookie.

I worried Meg wouldn’t get to see First Fallen. COVID had brought so much of the publishing world to a halt, and then Meg got her initial cancer diagnosis in March 2021. Publisher Ted Savas was largely on hold, but he scrambled to find a way to get her book into print so she could see it before anything might happen to her. An especially bad spell hospitalized her during a key part of the production process, but several of us rallied and got the book wrapped up for her. She fortunately rebounded, and after the book came out, she was able to enjoy its warm reception from critics and readers alike.

I worried Meg wouldn’t get to see First Fallen. COVID had brought so much of the publishing world to a halt, and then Meg got her initial cancer diagnosis in March 2021. Publisher Ted Savas was largely on hold, but he scrambled to find a way to get her book into print so she could see it before anything might happen to her. An especially bad spell hospitalized her during a key part of the production process, but several of us rallied and got the book wrapped up for her. She fortunately rebounded, and after the book came out, she was able to enjoy its warm reception from critics and readers alike.

She wrote about Ellsworth again for our most recent Emerging Civil War 10th Anniversary Series book Fallen Leaders. Copies starting arriving in contributors’ mailboxes around July 21, but I don’t know if Meg got to see it. She had just gone back to the hospital. “I’m so tired all the time,” she told me. “I’m hoping they can tell me why I’m always so tired.”

She knew by then that the cancer was back, although her medical team hadn’t given her a full prognosis yet. But she had seen one of the scans while they were doing it. She could see the new lesions in her lymph nodes. “They were big,” she said. “It’s bad, Chris. It’s bad.”

That last call came as I drove home from Appomattox Court House on Thursday, July 20. I’d given a talk titled “Grant’s Last Battle” that recounted the story of Ulysses S. Grant, facing financial ruin, trying to finish his memoirs while dying of cancer. The next day, a Friday, I would be on the road again for a trip to Grant Cottage, the location where Grant died, to speak on the anniversary of his passing.

I thought of Meg as I thought of Grant, wearing down, soldiering on, struggling to see the project through. I thought there’d be more time. I thought there’d be a few more weeks, maybe a month or two. Maybe I can try and fly out to California to see her after the Symposium, I thought, looking ahead to the upcoming ECW event on the first weekend of August. I didn’t want to think of a trip to California as a trip to say “Goodbye,” even if that’s what it would be.

* * *

Meg had wanted to be a historian all her life. Her father dissuaded her from that, concerned (as father’s can be) for the welfare of his daughter when she grew up. She could be a housewife or a secretary or a teacher. So, she became a teacher: middle school math. When I first met her, I could tell she loved math—but that’s because she found a way to enjoy almost anything. She lit up when she talked history, though. That’s when she came to life.

She started with ECW as a guest author in September 2011 and soon became one of our regular contributors. She seldom wrote about mud and blood, attracted instead to the human side of war. Offbeat stories fascinated her, perhaps resonating with the one-time goth girl still inside her.

Except the goth girl wasn’t entirely hidden away. Meg wore her hair bright purple, complemented by a pierced eyebrow and round, Mr. Peabodyesqe glasses—the sort of look apt to trigger dismissive scoffs from the stuffy Old White Men who make up the dustiest contingent of Civil War audiences. When she had her first publicity photo taken, Ted Savas wasn’t quite sure what to make of it. Would our crowd take her seriously? “She can present herself however she wants to present herself,” I told him. “If that’s who she is, that’s who she is.” Ted agreed.

Skeptics or not, Meg won readers over with her accessible writing and earnest desire to do well and her love of sharing interesting stories. She engaged with the history she wrote about, never shying away from the “gee whiz” factor of why something fascinated her. One of her gifts was to help people experience that same sort of “gee whiz” she did. This was, after all, cool stuff.

Meg’s experience with ECW led her to American Public University, where she earned her long-dreamed-of master’s degree in history, concentrating on the Civil War. I deeply admired her commitment and courage, in her mid-60s, to reinvent herself. She retired from teaching and did history full-time. It was like a long, soothing sigh from someone with sore, bare feet who’d been walking on blacktop all day before finally soaking them in a cool mountain brook. That was the sweet sound of success. She served as such a strong advocate for women in the field of Civil War history because of the experience with her father and the long road she had taken to reach the promised land. You can get there from here, she would remind other women.

As part of Meg’s reinvention of herself, she also fell in love. I’m not even sure I know the story of how she and Robert met, but their late-in-life romance provided her with important grounding. She had been married before but Robert was different. She adored him, and over the years, over and over, she’d tell me how lucky she was to have found him. She admired his patience and kindness—kindness that mirrored her own. He loved history and craft root beer and Meg’s wacky eccentricities. They shared a small bungalow with their cats, and they fed the birds on the porch, and set up their own free “little library” on a pole in the edge of the yard. Meg wanted to share her love of books with the world.

* * *

As my account of the battle of Jackson, Mississippi, reached its climax for the Chambersburg Civil War Seminarians, Old Abe the War Eagle “flapped his pinions and sent his powerful scream high above the din of battle.” One witness said Abe “was all spirit and fire.”

On the other coast, three time zones away from me and two time zones away from the Seminiarians, Meg was settling into the great beyond. Her own fire was gone, her spirit free. By the time Old Abe was sweeping into Jackson, Meg was, I later surmised, already chatting up Elmer Ellsworth or settling down to watch the great Yankees stars of old play an afternoon game. Those would have been Meg’s ideas of heaven.

I said my goodbye to Meg that evening, after calm had settled, by going with my family to a baseball game. Meg loved baseball, so I thought going to a game—doing something she herself would have enjoyed—would be an appropriate way to honor her. The Fredericksburg Nationals were hosting the Myrtle Beach Pelicans. Even after the sun set beyond the west rim of the stadium, temperatures hovered in the low 90s. The FredNats lost 12-0. A whisp of breeze kept us cool, though. And I could easily imagine Meg sitting along the third-base line, Robert next to her, her purple hair sticking out from beneath a red, white, and blue FredNats cap, talking and laughing and feeling bad for those poor boys out there in the heat and generally having a capital time.

“Every time I leave the person I love,” songwriter Casey McPherson had asked, “am I saying goodbye the way that I want to say goodbye to them?”

How about three tigers and a cheer?

Remember Ellsworth. Remember Meg.

Play ball.

Yes, sir. Three Tigers and a Cheer!!

Thanks for sharing your wonderful memories of Meg, it helps a lot. I always looked forward to her weekly articles about Walt Whitman; thank you for publishing them.

Thank you for this deeply moving and joy-filled tribute.

Well done, Chris.

Simply beautiful.

Thank you, Chris.

A beautiful tribute to your friend. I knew her not but after reading your eulogy I sorrow for the missed opportunity.

Chris, you live and breathe CW. Now I know you live for your friends in the present too. Bless you and thanks for sharing this touching story of your present day personal loss.

Well done, Chris. I never met her but I cannot imagine that she wouldn’t love this salute.

Beautifully written

‘Roll up! Eureka’s heroes,

On that grand old rush afar,

For Meg has gone to join you,

In the Big Camp, where you are.

Roll up! And give her welcome,

Such as only heroes can,

For well she battled for the cause,

For History and American.’

-Taken from ‘Eureka’, by Victor Daley.