What a Difference a Year Makes

1863 wasn’t just momentous for the United States as a nation. It was also a turning point for some of our most important historical figures.

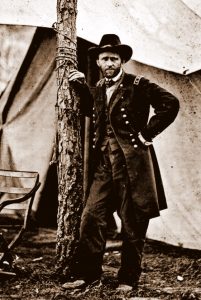

General Ulysses S. Grant entered 1863 in the wake of a brutal stretch of reversals along the Mississippi River. His two-pronged effort to capture Vicksburg had collapsed badly on both fronts. His main column had to turn back when Confederate cavalry burned his supply depot at Holly Springs on December 20, 1862. A few days later, Sherman was bloodily repulsed at Chickasaw Bayou.

These setbacks closed out a year filled with frustrations for Grant, despite opening with a great deal of promise for Grant at Forts Henry and Donelson. He was badly surprised at Shiloh, and despite eking out a win, his reputation suffered accordingly. As Halleck unified the Union’s western armies in the aftermath, Grant was relegated to a ceremonial “second in command” role. He watched from the sidelines as the massive army inched forward and allowed the Confederates under Beauregard to escape.

The victories at Henry and Donelson – and smaller wins at Iuka and Corinth later in the year – must have felt like ancient history as Grant rang in the new year. The benefit of hindsight can paint events with a false veneer of inevitability. You and I know how the story unfolds, but at the time, surely Grant had to wonder if he had finally scraped the bottom of his barrel of political goodwill.

On January 7, 1863, he wrote to his political patron and benefactor, Congressman Elihu Washburne, that “I am now feeling great anxiety about Vicksburg.” Even longtime aide and friend John Rawlins told a friend that he would resign in Grant’s shoes, and speculated that Grant may have lost Lincoln’s support. [1]

But Grant had the all-too-rare capacity to, at least sometimes, learn from his mistakes.

He gained valuable experience living off the land as he fell back after Holly Springs. Perhaps most important to his eventual success, he had enough bull-headed stubbornness to keep trying until he got where he was going, drawing on the vast reservoir of Union resources and manpower that allowed such a learning curve. Benefiting himself from hindsight, after the war Grant wrote of this moment that, “There was nothing left to be done but to go forward to a decisive victory.” [2]

For as grim as Grant’s prospects may have seemed at the start of 1863, the picture changed completely by the end of 1863.

Over the course of the year, he dealt major blows to the Confederacy’s ability to continue waging war. He captured Vicksburg in July, and Pemberton’s Confederate army along with it. That vicotry opened the “Father of Waters” and cut off the Trans-Mississippi from the main war effort. In the fall he rode to the Army of the Cumberland’s rescue and thrashed Bragg at Chattanooga, ensuring that the Confederacy gained no lasting strategic advantage from its bloody tactical victory at Chickamauga.

These were clear victories, maybe even decisive ones, in an era of warfare when that was a rare feat. It was with good cause that Lincoln wrote to him on December 8, 1863 to say, “I wish to tender you, and all under your command, my more than thanks – my profoundest gratitude – for the skill, courage, and perseverance, with which you and they, over so great difficulties, have effected that important object. God bless you all.” [3]

Looking ahead to 1864, Grant commanded all of the Union armies between the Mississippi River and the Appalachians. If his career had ended there, he was already one of the more successful generals of the war. Now he looked ahead to Atlanta. Unbeknownst to him, was about to ascend to even greater heights in the coming months.

What a difference a year makes!

[1] Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. DoverPublications. 1995. 173.

[2] Miller, Donald L. Vicksburg: Grants Campaign That Broke the Confederacy. 2019. 235, 259.

[3] Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 7. Via University of Michigan. 1809-1865.

Let’s see how “grim” Grant’s prospects were at the beginning of 1863. He had a vastly superior army both in numbers, equipment and supplies as well as great leadership at all levels. Complete control of the waterways with a magnificent navy well commanded. His cavalry was superly led and vastly superior to Confederate horse. His Confederate opponents were inferior in every respect especially numbers and does anyone think Pemberton, Bragg, and Joe Johnston were anything but failures? To me, it would have been shocking if Grant had not been successful.

Sometimes the bigger battle before the actual battle, is the one you wage within yourself. The Union and its resources allowed Grant to fight that battle “between the ears,” so to speak, and he gained an insight into himself from what he learned and experienced.

“He rode to the Army of the Cumberland’s rescue….He thrashed the Confederates…..” Meanwhile, old George “Slow Trot” Thomas was just lounging around, eating Pop Tarts, and waiting for the Wonderboy From Galena to save him no doubt???

And yet today, and for decades, try to imagine the American military without Southerners.