Book Review: Heartsick and Astonished: Divorce in Civil War-Era West Virginia

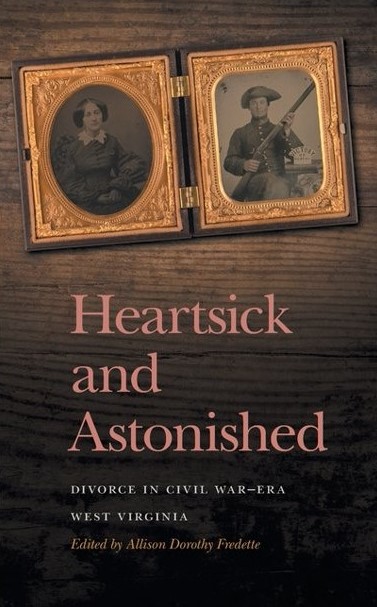

Heartsick and Astonished: Divorce in Civil War-era West Virginia. Edited by Allison Dorothy Fredette. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 2023. Softcover, 288 pp. $32.95.

Reviewed by Jon-Erik Gilot

I will be the first to admit that the type of social history presented in my latest read falls far outside my normal wheelhouse. Even so, when the subject matter quite literally covers my own backyard, I felt compelled to check it out. And so, when the opportunity arose to review this new study examining Civil War-era divorces in Wheeling, West Virginia, I jumped at the opportunity.

In Heartsick and Astonished: Divorce in Civil War-Era West Virginia, the editor presents a sample of twenty-seven divorce cases brought before the Ohio County, West Virginia, courtroom between 1850 and 1873. Like Randall Gooden’s recent publication, The Governor’s Pawns: Hostages and Hostage-Taking in Civil War West Virginia, Allison Dorothy Fredette discovered the cases she examined in the archives at the West Virginia and Regional History Center in Morgantown. As an archivist myself, I can tell you that many 19th century legal documents do not always make for the most exhilarating reading. However, Fredette realized the historical and cultural significance of these records and carefully transcribed and researched each case.

Fredette opens with a lengthy introduction, placing Wheeling within the context of the mid-19th century Upper South, as well as offering a history of divorce in America. Prior to the Civil War, Virginia courts limited individuals seeking divorce to claims of adultery, incurable impotency, and imprisonment. Heartsick and Astonished samples cases of adultery, abandonment, cruelty, and imprisonment, involving accusations against both husbands and wives and spanning racial, ethnic/cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds. From these civil suits we see shifting attitudes among husbands and wives toward marital expectations, gender roles, and divorce.

In examining Wheeling, Fredette found that in the ten years before the Civil War, the city’s spouses charged their mates with adultery more frequently than residents of neighboring southern states. While cases declined during the war, they spiked a staggering 284 percent in the postbellum years following West Virginia’s rewriting of Virginia code relating to divorce and married women’s property law.

Beyond testimony of the husband or wife, the suits also include testimony from friends, family, landlords, and business associates testifying to the veracity of the claims. As such, these cases offer a tantalizing window into a middle and lower class multicultural urban environment during the Civil War era. While Wheeling gained notoriety in the early to mid-20th century for its vice and prostitution (even garnering the moniker “Wide Open Wheeling”), the often-salacious stories found in these suits makes it clear that temptation also followed Wheeling’s men and women in the prior century.

As a Wheeling resident, I found names, residences, and locations that were familiar, even some within a few blocks of my office. Much like the celebrities of today who see their personal lives splashed across the tabloids, I am sure these 19th century individuals could never have anticipated the publication of some of their court documentation revealing many intimate details. I can enthusiastically recommend Heartsick and Astonished for anyone interested in fresh look at gender and identity in the Upper South during the Civil War era.