BookChat: We Fought at Gettysburg by Carolyn Ivanoff

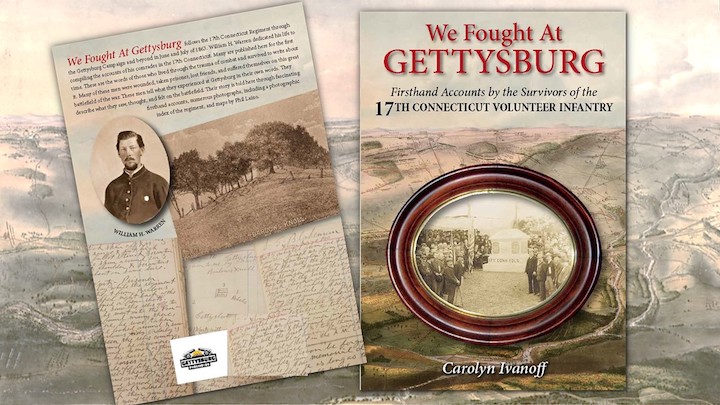

I recently had the opportunity to chat with author Carolyn Ivanoff about her new book We Fought At Gettysburg: Firsthand Accounts by the Survivors of the 17th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry (Gettysburg Publishing, 2023).

I recently had the opportunity to chat with author Carolyn Ivanoff about her new book We Fought At Gettysburg: Firsthand Accounts by the Survivors of the 17th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry (Gettysburg Publishing, 2023).

“These personal accounts are framed and woven into the sequence of the three-day battle, the aftermath, and beyond, and are presented in context,” Carolyn told me. “There are accounts by the survivors, the wounded, the prisoners, care givers, and men who were seared by the loss of their comrades and friends.”

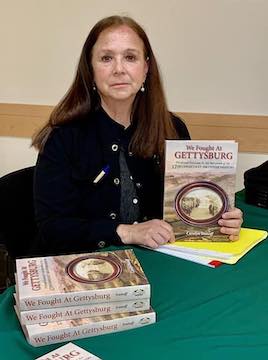

Carolyn is a retired high school administrator and independent historian. She writes and speaks frequently on American history at local, state, and national venues. In 2003, Carolyn was named Civil War Trust’s Teacher of the Year.

Who are these fellows from Connecticut? What can you tell us, briefly, about the regiment and backgrounds of the men?

The 17th Connecticut, the Fairfield County Regiment, was formed in 1862 in response to Lincoln’s call for 300,000 more men to put down the rebellion. Connecticut, a small state, was politically divided, but the loyal men from Fairfield County heeded the call. The 17th was the only Connecticut regiment formed from one county, and it was filled quickly in a matter of a few weeks in the summer of 1862.

The men came from all walks of life. Some had trades, some were from wealthy families, some were immigrants. William Noble, a lawyer and sometime-partner of P. T. Barnum, was appointed the colonel of the regiment. The first lieutenant colonel of the regiment was Charles Walter, born in Denmark (he would be killed at Chancellorsville). Elias Howe, Jr., inventor of the sewing machine and the richest man in Connecticut, patriotically enlisted as a private in Company D.

Some of the men came from solid Democratic families that were not supportive of the war, or the Lincoln administration, and this caused family frictions and heartache for these men throughout their service.

What got you interested in the regiment?

I’m a product of Fairfield County. I was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and raised in Shelton. I went to school in Shelton, and then taught history at Shelton High School for many years before taking on a housemaster position at the high school. I also sat on several boards of local historical societies. I was always interested in local history and in the history of Fairfield County.

Many of the men of the 17th Connecticut lived in homes in our communities, had descendants that still resided in those homes, or in town. Street names and cemeteries were reminders of this Civil War generation and their legacy. Often, members of the community would send letters or documents up to the high school for me to see, or review, or to transcribe. Although my family are 20th century immigrants, I was always fascinated with the Civil War and, over the years, I learned quite a bit about these men from the 17th Connecticut and who they were.

What was the regiment’s service record before Gettysburg?

The 17th Connecticut mustered in on August 28, 1862, and was immediately sent to Baltimore. They were assigned to the Eleventh Corps. They missed the battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg but participated in the “Mud March.” They saw no combat in 1862.

The Battle of Chancellorsville was their first combat, and it was a disaster. As part of the Eleventh Corps, they were placed at the very tip of the Union line, the flank that was in the air. Late in the afternoon on May 2, two companies of the 17th, G and I, were on picket duty when Jackson’s 28,000-man flank attack came screaming out of the woods and rolled up the Union line.

As members of the Eleventh Corps, the “German Corps,” the effects of the humiliating defeat at Chancellorsville would follow the survivors to Gettysburg. The Eleventh Corps was branded as “Howard’s Cowards” and “The Flying Dutchmen,” the scapegoats of the Army of the Potomac.

Where were they at Gettysburg and what happened to them?

The 17th Connecticut at Gettysburg was assigned to the Eleventh Corps, 1st Division, 2nd Brigade. General Francis Barlow was the division commander and General Adelbert Ames commanded the brigade. The regiment was led at Gettysburg by Lt. Colonel Douglas Fowler, who would be spectacularly decapitated during the first day’s fighting.

On the late afternoon of July 1, Barlow aggressively rolled his division out onto a small knoll that would thereafter bear his name. His men were in a salient at the end of the Union Eleventh Corps line and would be thoroughly outnumbered and flanked in an eerily similar fashion to the Chancellorsville disaster. rapped in a two-pronged Confederate assault that far outnumbered them, the Federal regiments were crushed, and those not killed, captured, or wounded retreated through the town of Gettysburg to reform on East Cemetery Hill.

Throughout the day on July 2, the 17th Connecticut on East Cemetery Hill remained in place, subject to almost constant sniper fire from the houses along Baltimore Street picking off men and battery horses and artillery men throughout the day as the sounds of heavy combat rolled up from the south of the Union “fish hook” line—along with many rumors about horrific fighting in the Peach Orchard, Wheat Field, the Round Tops.

Toward evening, the Confederate artillery barrages began from Benner’s Hill, directed toward them. Union artillery responded. On the right, Culp’s Hill erupted into heavy fighting, and as night fell, the Union lines on East Cemetery Hill found themselves under attack by Louisiana and North Carolina troops that broke through in the dark to attack the Union artillery batteries at the top of Cemetery Hill. The 17th Connecticut and the 75th Ohio at the bottom of the hill managed to hold their positions, engaging in hand-to-hand combat as the Confederates broke through other regiments along the line.

The Confederates that managed to attack the artillery were driven off in fierce combat and the Second Corps sent reinforcements. Finally, on the night of July 2, the Union line was secured, and General Meade held his council of war.

On July 3, the regiment continued to be harassed and engaged in almost constant sniper fire. In their position below East Cemetery Hill, they were mostly sheltered from the great afternoon barrage and the subsequent Confederate attack that was repelled.

On July 4, the 17th Connecticut was one of the first regiments to send skirmishers into Gettysburg to secure the town after the Confederate retreat. The men from the regiment went over the ground where they had fought July 1. They liberated the hospitals in the town and the Alms House where their wounded were held, and they went back over the fields of the first day’s combat to locate wounded and identify dead comrades and to bury the dead.

Many of the wounded of the regiment were consolidated from field hospitals in the town and farms and sent to the Eleventh Corps Hospital at the George Spangler Farm. The survivors of the regiment left Gettysburg with the Army in pursuit of General Lee on July 5, 1863.

How did you go about collecting the accounts that appear in your book?

In writing the book, I relied on an extensive bibliography, soldiers’ correspondence, and diaries where I had access to them, but the heart of the book are the words of the soldiers themselves and their first-hand accounts gathered in a remarkable, multi-volume, unpublished manuscript compiled by Private William Warren, Company D. Warren had hopes of writing a regimental history, but it never came to fruition. He drew from his own diary, the diary of his comrades, and extensive correspondence with survivors of the regiment from 1865 until his death in 1918. Over the years, Warren amassed a thirteen-volume, rambling, unwieldly manuscript along with several boxes. The manuscript compiled a range of personal narratives from the survivors, the wounded, the prisoners, those who lost their friends or nursed them in the hospitals, and those who soldiered on after the battle.

The repository of the manuscript is the Bridgeport Public Library. The manuscript has resided there for years, and no provenance has ever been located. The manuscript is massive, rambling, challenging. It represents a life’s unfinished work, where history remains alive in its sprawling volumes. My challenge was to confine myself to the most relevant material and accounts on the Gettysburg Campaign and to distill, define, and illuminate for the reader the experiences of the 17th Connecticut in that battle and its aftermath. I needed to present the first-hand accounts by these soldiers in a respectful, readable, and compelling book that honored their service, sacrifice and memory. I hope I have succeeded.

How long did the book take you?

The writing of the book itself took four years, from 2019-2022. It was published in March 2023. I had been familiar with 17th Connecticut for years and had used the manuscript for researching individual soldiers of the regiment and their experiences. I had done presentations and programs on these men of the 17th for local historical societies and libraries. When I proposed a full-length book to Gettysburg Publishing, Kevin Drake, the publisher and owner, accepted my proposal, and We Fought at Gettysburg became a reality.

Is there a particular veteran or account that has really stuck with you as a favorite?

There are several documents and accounts that I do find most fascinating and unique. I’ll highlight several of them:

- The various eye-witness accounts of Lt. Colonel Fowler’s death and the attempts to save his body and the remarkable letter from the last man to have possession of Colonel Fowler’s body before he was captured on the field. And lastly, the accounts of men from Connecticut who came to Gettysburg after the battle to search for Fowler’s body in hopes of identifying it and bringing it back to Connecticut for an honorable burial.

- The several accounts of family members who came from Connecticut after the battle, and the hardships and heartbreak they endured to retrieve the bodies of their dead and bring them home.

- The diary account and especially the itemized expense document from the diary of Rev. Nash who listed line-by-line every cost he incurred in the retrieval, preparation, transport, and funeral expenses in bringing his nephew’s body home to Ridgefield.

- My favorite letter was written by a wounded J. Henry Blakeman, Company D, at the Eleventh Corps Hospital at Spangler Farm on July 4 in the pouring rain to his mother in Stratford, Connecticut.

- I was especially fascinated by the photographs of the men that Warren accumulated. I was able to match many of them with the words and accounts they left behind or the comrades whom they described in their accounts. Organized in such a manner, wherever possible, they are no longer nameless or faceless and bear witness to the events and history of their words.

What can the experience of this regiment help us understand about the larger battle?

I believe that the personal accounts that these men left can tell us much about the larger battle. Their accounts, in their own words, that these men wrote as survivors, prisoners, wounded, combat veterans, speak for the experiences of others like themselves who witnessed what was Gettysburg. For example, several personal accounts describe many Union men were barefoot going into the battle. This is a revelation of what the larger army experienced. Being unshod is not a condition often associated with the Union army. (Kent Masterson Brown estimates in his book on Meade that perhaps half of the Army of the Potomac was without shoes.)

After the book came out in the spring, I met a man at the Eleventh Corps Hospital at Spangler Farm at a Gettysburg Foundation event. He told me that he had read the book with fascination, especially the prisoner of war accounts. His ancestor from a Pennsylvania regiment had been captured at Gettysburg. He was struck with the prisoner accounts that helped him understand what his ancestor endured. The long, difficult walk down the Valley Pike to Staunton, Virginia to be loaded onto a cattle car bound for prison camp in Richmond, the hardship and starvation, and what these men described. He said it brought him closer to his ancestor and the past.

In speaking for themselves, in giving their accounts, these men spoke for thousands of others who endured what they endured, and who bore witness to Gettysburg, its aftermath, and its legacy.

Anything I haven’t asked you that I should have?

I’d like to conclude with my future hope for this book. I hope that as time passes, the book will remain relevant for those who wish to know what these citizen soldiers thought and felt about their Civil War service and sacrifice at Gettysburg. I hope that the arrangements of these accounts in their context will help readers understand more about Gettysburg. I hope readers of the personal accounts of these men will understand and recognize the importance of firsthand accounts in shedding light on history as well as on the battle of Gettysburg and its aftermath.

Congrats on the book, Carolyn. I’m in Trumbull and have been interested in the 17th CT for years. (My book, “Twelve Days,” about the first days of the war, was published this summer by Potomac Books and reviewed on Emerging Civil War.) Link here: https://emergingcivilwar.com/2023/07/13/book-review-twelve-days-how-the-union-nearly-lost-washington-in-the-first-days-of-the-civil-war/

Looking forward to reading your book. Interestingly, the company rosters don’t have a lot of Trumbull residents.

I found an old newspaper account of a soldier from the 17th who survived Gettysburg but was murdered in Bridgeport in 1886 by an opioid crazed jealous husband. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/31350466/william-h-adams