Glorifying War? Reflections on Hollywood’s 1951 Adaptation of The Red Badge of Courage

ECW welcomes back guest author Heath Anderson

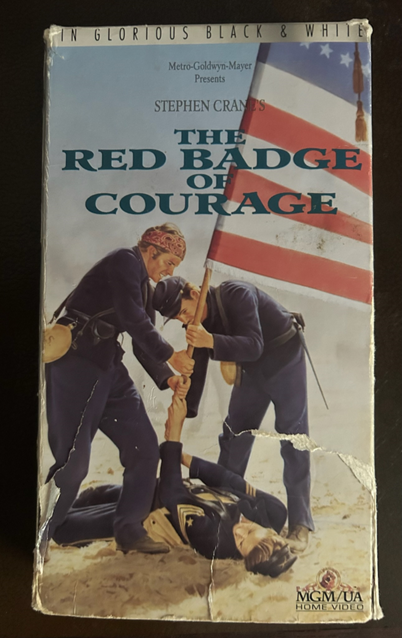

I’ll lay my cards on the table: I consider The Red Badge of Courage to be the greatest Civil War film ever made. With World War II hero Audie Murphy as Henry “the Kid” Fleming and fellow veteran Bill Mauldin in the leading roles, director John Huston’s adaptation of Stephen Crane’s classic novel captured my imagination as a child. In countless viewings with my grandmother, I watched Audie Murphy carry the stars and stripes toward the faceless Confederate lines, the Battle Hymn of the Republic roaring to life in the background, and I felt like I had been transported into the past, confronted with something profoundly significant that I could not explain. I have often wondered over the years what about this film resonated with me so deeply. Does a film made in the afterglow of Allied victory in WWII still have relevance for our modern understanding of the Civil War? Is my love for this film merely nostalgia, completely disconnected from the real experience of the war and the indescribable horrors of the battlefield?[i]

As an academic, I am almost required to be cynical. There is nothing glorious about war, nothing to be celebrated amidst so much death and destruction. We often hear today that in war, no one wins, and scholarship on the Civil War has recently returned to this framing. In what has been called the “dark turn,” historians have argued that little of any lasting significance was achieved by the United States’ victory in the Civil War. As one scholar has written about this trend, “The Civil War emerging from this new scholarship is just another messy, ghastly, heartless conflict between two parties who were both, to some degree, in the wrong.” Crane’s narrative in The Red Badge of Courage, of a boy who overcomes his fear of battle to come out a man by standing firm and doing his duty, could be interpreted through this lens, as the celebration of a martial masculinity that ignores the abject horrors of the conflict.[ii]

I contend that this would be a mistake. Not only is the film a more visceral depiction of combat than many subsequent Civil War films, but it also celebrates a singular message about why Union soldiers fought and the significance of their doing so. That reason is the Union Cause: the cause of ordinary Americans coming together to preserve their government in the face of an armed rebellion, in which victory was not assured and required great sacrifice. If such triumphalism feels out of place to us today, that is because the United States’ victory in the Civil War seems to have been all but inevitable. That it could have turned out differently, and that it did not, is one of the film’s lasting impressions. Henry Fleming’s victory over his own personal fear is therefore a victory for the nation as a whole and one worth remembering.[iii]

Soldiers in Fleming’s fictional 304th New York infantry do not directly expound upon the Union cause, but they do allude to it by demonstrating one of its central components: the citizen soldier tradition. For nineteenth-century Americans, there was no greater marker of citizenship than ordinary men pausing their civilian lives to defend the flag and government in its hour of peril. Union citizen soldiers believed they were following in the footsteps of the founding generation and upholding their sacrifices to establish a free and self-governing republic with opportunity for all men to better their condition, something the slaveholder’s rebellion threatened.

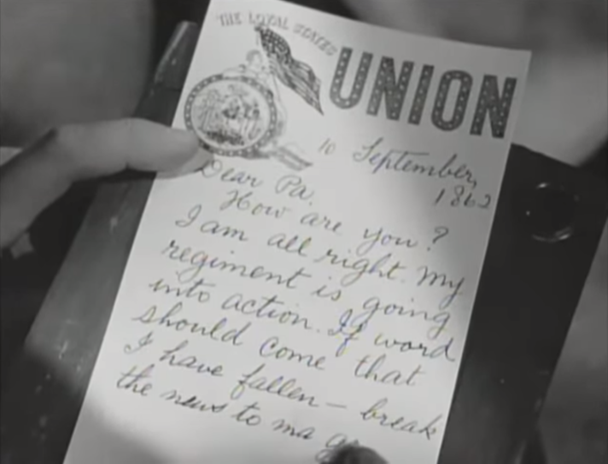

As Henry’s friend Tom Wilson explains to him when asked about his reasons for fighting, “My grandpappy fought with Washington; it’s in my blood, I reckon.” The central struggle in the film, of Henry and his comrades overcoming their fear of death, is not simply a human reaction, but also a representation of the thousands of nonprofessional soldiers who took up arms to fight for the cause. As Henry Fleming writes a letter home on paper adorned with patriotic imagery, it is not hard to imagine that their characters would concur with the assessment of Union soldier Henry E. Richmond, who described his service as “the noblest cause that a loyal citizen can do—the suppressing of the rebellion against…our country & the best government that God ever vouchsafed to his children.”[iv]

In addition to this deeper meaning, The Red Badge of Courage is first and foremost a unique Civil War film. Bringing the drudgery and uncertainty of soldiering in Crane’s novel to life, the film shows us the monotony of drilling in camp with the memorable narration that “war was simply a matter of waiting. Waiting and endless drilling.” This tedious routine is interrupted by frantic rumors of the coming campaign, followed by several evocative scenes, such as Henry and his comrades’ journey to the battlefield across a river, a nearby homestead, and forest trails. Throughout the trek to the battlefield, the film maintains a foreboding sense of the trepidation of individuals swept up in a much larger struggle.

The film’s depiction of battle is also the opposite of an uncritical glorification of war. While it lacks the special effects and gory imagery of modern war films, its battle scenes convey the fury of Civil War combat in an unsettling fashion. Rather than an omniscient recreation of a battle that most viewers already know the result of, Fleming and his unit come upon the battlefield unexpectedly after a tense march. While we are presented with an imposing wide shot of the field before them, it is wreathed in smoke and our perspective remains that of Henry Fleming’s, making any attempt to discern tactics and strategy pointless. As his unit is rushed inexorably into line to replace swarms of their retreating comrades, the viewer is left uncertain as to Henry’s fate, but also cognizant of a massive release of tension expressed by many Civil War soldiers as they finally entered battle. As one Illinois soldier put it, “the greatest strain was…listening to the oncoming roar of battle.” However, once engaged he stated that “I forgot where my heart was and had no desire to run.”[v]

Henry, of course, does initially run, but not before standing down a rebel assault and being faced with the most harrowing experience for all Civil War soldiers: hand-to-hand combat. The camera pans to each soldier in Henry’s unit as they discharge their rifles and stop the rebel attack. There is no dramatic swelling of music, no exaggerated acts of heroism, just the grim work of killing. This scene functions almost as an exorcism of their fear, recalling one historian’s observation that firing served as “a positive act” and a “physical release” for Civil War soldiers’ emotions. The comedown from the emotional high of battle is represented following the Confederate retreat, when Fleming’s comrades seem stunned at their survival, and one remarks, “they look much bigger through the powder smoke.” But their peace is quickly shattered by the frantic realization of an impending second attack, this time with the bayonet. As Henry returns to the firing line, the rebel yell grows louder, and their charge bursts out of a swirling cacophony of noise and smoke, colliding with the Union line and sending Henry scampering to the rear and making the viewer feel the urge to join him. There are few more memorable portrayals of the maelstrom of Civil War combat from the perspective of the common soldier.[vi]

Ultimately, Henry Fleming redeems himself, and the satisfaction of victory that he and his brothers-in-arms enjoy at the end of the film might seem too tidy to us. Where are the shattered bodies, the years of trauma, and the realization that many issues of the Civil War were far from settled after the guns fell silent? However, as the 304th marches out of frame for the final time and Henry looks up hopefully at the sun breaking through the trees, we might do well to take the message of the pride he felt in victory seriously. As one historian has written about the triumph of the United States, “Northern soldiers…had fought to reunite a nation shattered by slavery. And they had won.” With Union victory, the government of the founders had been preserved, the Constitution upheld, and the nation reunited. If these results came to seem less important over time as the war generation passed on and the threat of secession dividing the nation receded, it speaks only to the completeness of the triumph most loyal citizen soldiers felt they had achieved on the battlefield. The Red Badge of Courage magnifies this sense of triumph because of the immense sacrifices thousands of real soldiers made to make it possible. It remains essential viewing for anyone interested in the American Civil War.[vii]

Heath Anderson is a Ph.D. candidate at Mississippi State University under the direction of Dr. Andrew Lang. He grew up in Virginia and developed a passion for history and the American Civil War from a young age, traveling to numerous museums, battlefields, and living history events. Heath attained his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Virginia Commonwealth University where he wrote a thesis on Confederate General William Mahone and the Readjuster Party. Heath’s primary research interest is the period of Reconstruction following the war, and how local politics and events influenced federal policy on Reconstruction.

[i] The Red Badge of Courage, directed by John Huston (1951; Santa Monica, CA: MGM-Warner Home Video, 1993), VHS.

[ii] Yael A. Sternhell, “Revisionism Reinvented?: The Antiwar Turn in Civil War Scholarship,” The Journal of the Civil War Era 3, no. 2 (2013): 249.

[iii] My interpretation of the significance of the Union Cause is inspired by Gary Gallagher’s The Union War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011).

[iv] Gallagher, The Union War, 107.

[v] Jonathan M. Steplyk, Fighting Means Killing: Civil War Soldiers and the Nature of Combat (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2018), 52.

[vi] Ibid., Steplyk quotes military historian Paddy Griffith, 53.

[vii] Caroline E. Janney, Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 172.

Excellent piece. In view of more recent movies, The Red Badge of Courage has receded in memory for many. Thanks for reminding us. If this article is any example, you have a fine future ahead of you in the Civil War field.

I’m glad you enjoyed it! I appreciate the kind words.

I agree with you. Red Badge of Courage is my favorite Civil War movie. I was drawn to it by Audie Murphy, a real combat hero. I have read that the director had a hard time convincing Audie to run from combat for the movie. I am a Bill Mauldin fan, also. Love his Willie and Joe cartoons from World War II. Excellent article and well written and thought out.

I recently read that too, about Audie Murphy. I always wondered how he felt acting in a war movie vs his real combat experience. Thanks for reading!

Loved it Brings back all of this kid’s imaginings about The Red Badge of Courage. Tis a pity fighting for our country is not currently seen as “…the noblest cause…”

Mike Evenson

I appreciate it. Thank you for reading!

Thank you for sharing this, Heath — really interesting article. I’ll confess I haven’t seen the movie, but I’ve added it to my to-watch list!

Excellent and interesting presentation of the subject. Thank you. But now I have to find that old movie.

I used the Red Badge of Courage as a motif in writing my own Civil War story of my ancestor’s experience.

Supposedly when director John Huston asked Murphy to act frightened in one scene, he replied “how?”

RB of C is frustrating for me, because it was edited badly by the studio, and could have been even better

although I agree that its a remarkable film.

Gary Gallagher wrote that the Union cause is the true “lost cause” because its victory was so complete: the authority of the federal government, the preservation of the Union and the Constitution were upheld. Its our reality. But that motivation for Union soldiers has been superseded by the emancipation narrative, the abolition of slavery an achievement that was eroded by debt peonage, Jim Crow, and various forms of discrimination that persist into our times.

Union troops fought for the Union, with the destruction of slavery a means to that end. Although Black Union soldiers saw it the other way around.

As Lincoln believed, preservation of the Union had to be the primary mission, because without that, there would be no emancipation or abolition.

As far as ‘best’ civil war film, I would submit “Glory” rather than “Red Badge of Courage.” Gallagher would doubtlessly say, its because as a modern person I accept the emancipation narrative over the preservation of the Union cause. I still think its a good movie.

Thanks for reading. I didn’t know about the missing footage when I first watched the movie years ago. I wish it still existed somewhere!

“Dear Pa…my regiment is going into action. If…I have fallen, break the news to Ma”

1. I’d rather be illiterate if I were to receive that letter.

2. In reading the book I thought his Ma was a widow.

American WWII veterans played important roles in many great movies, but Audie Murphy couldn’t have been a better choice here. Thanks for a great article, good luck – hope to call you doctor!

It is interesting comparing it to the book. I think, in some ways, it distills the best parts of Crane’s narrative while adding some drama for the screen. Certain details are definitely changed, though. Thanks for reading and for the kind words!

“We often hear today that in war, no one wins, and scholarship on the Civil War has recently returned to this framing. In what has been called the ‘dark turn,’ historians have argued that little of any lasting significance was achieved by the United States’ victory in the Civil War. As one scholar has written about this trend, ‘The Civil War emerging from this new scholarship is just another messy, ghastly, heartless conflict between two parties who were both, to some degree, in the wrong.'”

I don’t disagree with the author’s presentation of the pessimistic view of the Civil War, above, but Jeff Daniels monologue portraying Joshua Chamberlain to the veterans of the 2nd Maine who were assigned to the 20th Maine belies that view, as do many of the descendants of slaves whose legal servitude ended with the passage of the 13th and 14th Amendment albeit the the racism that still denies true equality. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ZpQ5W1AV0g

But as an amateur historian myself, allow me to nit-pick about the crossed muskets on the cap of Tom Wilson. The bugle was the symbol of the infantry until 1876, when the Army decided to use crossed muskets to signify that branch (check out Jeff Daniel’s cap in the above video).

I appreciate your original perspectives on a forgotten classic Book and Movie. I believe President Lincoln and Union soldiers rallied around the same common cause: the belief that preservation of our Union was the right thing to do and that “ all men are created equal…”

” …. ordinary men pausing their civilian lives to defend the flag and government in its hour of peril.” Its a shame that to “defend” that government in its supposed “hour of peril,” Henry and his comrades found it necessary to invade another country.

Tom

Sir – forgive me or forgive me not, but I can resist a little gibe, At least they didn’t invade Canada. 😉 I know, not likely to set the table on a roar.

thanks Heath … what a great essay about an important historical topic, especially if you are a historian of War & Society or if you’re just curious about what compels soldiers to fight … as Dr. Gallagher suggests, loyal citizens of the United States enlisted to save the Union … but historians now suggest it was group cohesion and their loyalty to one another that kept infantry soldiers in the fight … and i did not know that Bill Maudlin was in RB of C. thanks again.

Congratulations on an outstanding post. RBOC stands alone among Civil War fiction in my estimation also.