There will be no turning–um, well, okay…. We’ll turn back.

When Ulysses S. Grant crossed the Rapidan River in the spring of 1864 to begin what became the Overland Campaign, he famously told a reporter, “There will be no turning back.”[1]

The comment was more than bravado. It was more, even, than a simple articulate of strategy. Grant, in fact, had a deep, personal aversion to “turning back,” which had nothing to do with his military career whatsoever.

In his memoir, written in 1885, he talked about a habit he first developed as a young boy:

One of my superstitions had always been when I started to go any where, or do anything, not to turn back, or stop until the thing intended was accomplished. I have frequently started to go places where I had never been and to which I did not know the way, depending on making inquiries on the road, and if I got past the place without knowing it, instead of turning back, I would go on until a road was found turning in the right direction, take that, and come in by the other side.[2]

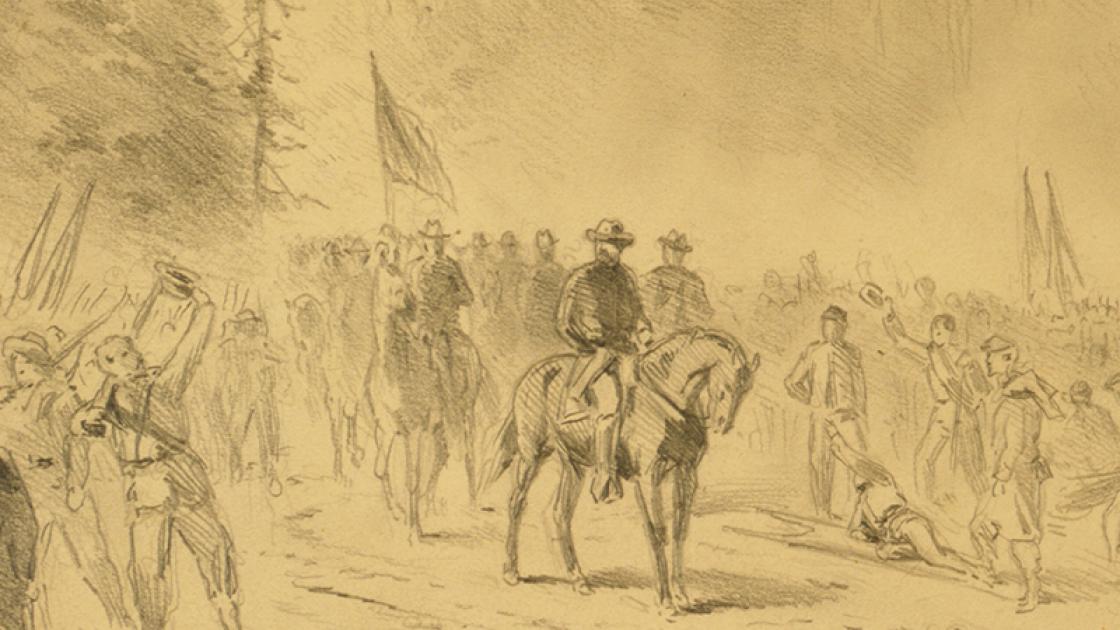

His decision to move on from the Wilderness on the night of May 7, 1864, is often seen as the first true test of his “no turning back” dictum. At the Brock Road/Plank Road intersection, Grant led the Federal army down Brock Road toward Spotsylvania Court House rather than back along the Plank Road toward the safety of Fredericksburg.

What most people don’t realize about this famous episode, though, is that Grant did, indeed, have to turn back.

During the march to Spotsylvania, Grant and Meade and their staffs got lost for a short spell. They had been riding down Brock Road at the lead of the Federal column but pulled aside because “their headquarters escorts and wagons were delaying the advance. . . .” The woods were still on fire along parts of the main road, said Horace Porter, a member of Grant’s staff, so “the party turned out to the right into a side road.”

The night was dark and the dust thick, Porter reported, and soon the guide lost his bearings. Eventually, another staffer found a route back to the Brock Road. According to Porter:

General Grant at first demurred when it was proposed to turn back, and urged the guide to try and find some cross-road leading to the Brock road, to avoid retracing our steps. This was an instance of his marked aversion to turning back, which amounted almost to a superstition. He often put himself to the greatest personal inconvenience to avoid it. When he found he was not traveling in the direction he wished to take, he would tray all sorts of cross-cuts, ford streams, and jump any number of fences to reach another road rather than go back and take a fresh start. . . .

The enemy who encountered him never failed to feel the effect of this inborn prejudice against turning back. However, a slight retrograde movement became absolutely necessary in the present instance, and the general yielded to the force of circumstances.[3]

Grant did not let the backtracking deter him from his larger plan, however. As he wrote to Washington just days later, “I intend to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.”[4]

And he did.

————

[1] Louis M. Starr, Reporting the Civil War: The Bohemian Brigade in Action, 1861-65, (Collier Books, 1962), 246

[2] Ulysses S. Grant, The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant (New York: Charles S. Webster & Co., 1885), 49-50.

[3] Horace Porter, Campaigning with Grant (New York: Mallard Press, 1991), 81.

[4] Grant to Halleck, 11 May 1864, O.R. XXXVI, Pt. 2, 627.

Fascinating. Perhaps his loathing was fueled by his earlier life experiences, where he indeed seemed to be falling down a deep slope from military resignation to civilian failure. He recouped himself with his bulldog determination, and would thereafter never surrender the initiative (save when being screwed by Halleck, post Shiloh).

Holly Springs?

From Holly Springs he change route to the Mississippi past Vicksburg

Another example of Grant turning back or at least falling back tactically, was on April 6 during the first day of the battle of Shiloh when his army was suddenly attacked by Confederate forces. Realizing that he would have reinforcements by the end of the day, his army tactically fell back gradually during the day to stronger defensive positions near Pittsburg Landing that could be better defended with massed artillery and river gunboats on the Tennessee River, essentially trading space for time. Grant launched an offensive assault the next morning on April 7 and forced the Confederate army to retreat to Corinth.