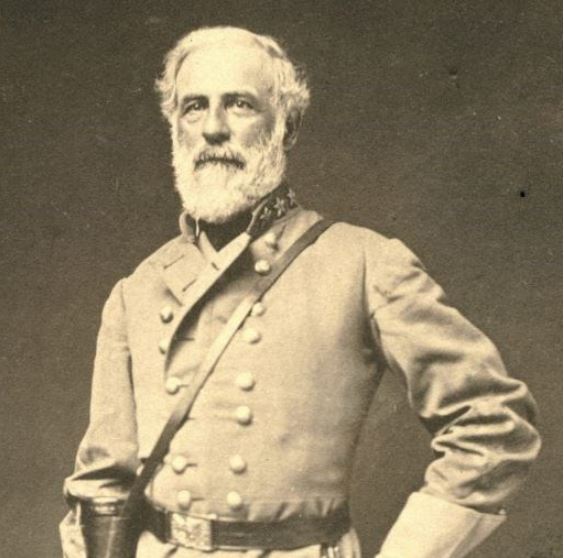

An Emerging Image of General Lee at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville

Stately. That’s the word I probably would have picked ten, maybe even three years ago, to describe Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The visuals that would have come to mind would have been Mort Kunstler paintings. There are times in primary sources that people saw Lee in that type of gentlemanly grandeur, and that image was how Lee’s post-war fan club wanted him to be remembered. However, there were other sides of Lee’s character that went on display during the Civil War years.

Recently, Lee’s image in public and academic history has taken a downfall. Sometimes, literally. Sometimes, more figuratively. There is a danger in making people larger than life, bronzing their image and memory, and elevating them as peerless examples. In monument and memory controversy, I’ve sometimes wondered how Lee (or other controversial figures) might have felt about their “legacy” and monuments. Would they have liked the ego boost? Or would they have been profoundly uncomfortable by the elevation?

Over the past couple of years, I’ve been wrestling with the idea of a different Robert E. Lee in the military scenes. Lee who is not always stately, calm, and collected. Lee who gets frustrated easily, hides his ailing health, snaps at his staff, and relentlessly pursued elusive victory. It’s Lee from the primary sources, not Lee in popular paintings. I didn’t go looking to re-imagine this image of Lee…it’s just sort of happened as I’ve been reading more. I don’t find the new image of Lee the result of a researcher’s animosity. Rather, I’m finding the historical Lee infinitely more interesting and complex, even if some of the stateliness has faded.

The six month period between December 1862 and May 1863 are a good case study for finding pieces of real Lee. I’d grown up with the image of calm Lee watching the slaughter at the battle of Fredericksburg and remarking “War so terrible…” and a grand Lee riding into the Chancellorsville crossroads, content in his victory and worried about wounded Jackson. But the Lee portrayed in paintings or other art is different than Lee seen by those closest to him during those months.

By December 1862, Lee had a list of victories that out-shown his defeats and difficulties in 1861. From “saving” Richmond to a smashing victory at Second Manassas and an audacious campaign into Maryland, Lee had been positioning for a crushing victory and keeping his enemies guessing. Victories were not enough. Lee needed a victory that decisively destroyed the Union’s Army of the Potomac and, ideally, followed that win with a strategic city capture or something of that scale which would force the Federal government to want peace…or decisively bring a European power to the Confederate side.

From Telegraph Hill, the panorama of war lay in front of Lee. The town of Fredericksburg, the sloping ground raked with artillery crossfire from Marye’s Heights, and the open, flatter ground in front of Jackson’s hastily formed line. On December 11, 1862, Union General Burnside played into Lee’s plan with his delaying struggle to get pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River. December 12 and its lull gave Lee time to get “Stonewall” Jackson and most of the Second Corps into a more consolidated position, roughly between Prospect Hill and Telegraph Hill, utilizing some of the high ground along the line and connected by an interior road.

Throughout December 13, Union attacks pressed toward the Confederate line. Some Union regiments broke through an unguarded place in Jackson’s line, but a counterattack drove them back. Attacks repeated and intensified against Marye’s Heights, leaving through ground in front of the high ground carpeted with dead, dying, wounded, and trapped survivors. The Confederate defensive lines held, and the high casualties to the Union ranks increased the Fredericksburg victory’s value in the eyes of the Confederate press.

However, despite ending 1862 with a loudly praised victory, Lee was upset by Fredericksburg. Startled by the news that the Union army had successfully retreated back across the river and cut loose their pontoon bridges, Lee’s expression had “deep chagrin and mortification, very apparent to the observer…though nothing of the sort was expressed in words.” Later in December, Lee still brooded over his escaped enemy and wrote: “I was holding back…and husbanding our strength and ammunition for the great struggle.” He claimed that if “I had divined that it was to have been his only effort, he would have had more of it.” As historian Frank O’Reilly points out in his battle study, “Lee considered the battle [of Fredericksburg] only half won.”[1] The Union army had been bled, but it had not been decisively defeated. His enemy settled into winter camps just across the river and would be ready to fight again in the spring.

The public’s perception of Lee’s battlefield victory at Fredericksburg contrasted to his own understanding and regrets. Newspapers hailed Fredericksburg as a great Confederate victory, but Lee understood that it had not been enough of victory.

The winter of 1862-1863 saw changes and challenges in personal areas of Lee’s life. His daughter Annie had died in October 1862 and, from his writings, he was evidently continuing to grieve. A granddaughter had also died after just seven weeks of life, and her death—barely a week before the battle of Fredericksburg—also saddened Lee. By late winter, Lee also had physical ailments, including “a good deal of pain in my chest, back, & arms.”[2] He downplayed his pain and symptoms in letters to his family but eventually admitted to his son Custis that he felt “weak, feverish, and altogether good for nothing.”[3] Modern medicine looking at the history of Lee’s health has led to suspicion of heart attacks or heart disease.[4] Lee’s temperament also flared during the winter months. He barked at staff officers for accidentally admitting undesired persons into his headquarters tent and giving a chilling response to another junior officer. Lee might have recognized his foul mood, writing to his son, “I fear you will think I am in a bad humour & I fear I am.”[5]

By the time the Chancellorsville Campaign opened, Lee’s health had improved, and he seemed once again ready to pursue the elusive, decisive victory. Union General Joseph Hooker’s plans and lack of swift follow-through gave Lee opportunity to take the offensive. Perhaps remembering Fredericksburg, he committed large numbers of troops to attacks, but was hampered by the need to divide his army multiple times to face the divided portions of the Union army (Hooker at Chancellorsville, Sedgwick at Fredericksburg).

On May 3, 1863, the Confederate forces around Chancellorsville reunited after the separation intentionally caused by Jackson’s Flank Attack on the previous day. Yelling Confederates drove Union corps from their defensive positions around Chancellorsville, and Lee rode into the crossroads clearing in a scene that one of his staff officers later imagined as a martial scene that could have inspired the Ancients to create their legends of the gods of war. Again, Lee had won a battlefield victory…but it was not enough. Lee needed to destroy, not just defeat, the Union army. He turned his attention to the Union troops commanded by General Sedgwick, now isolated against the river just north of Salem Church. Planned attacks on May 4 delayed and Lee was “in a temper,” according to Colonel Edward Porter Alexander who explained:

“I could not comprehend at the time whom it was with, or what it was about; & I never have exactly found out yet. But the three ideas which his conversation with myself & others in my presence seemed to indicate as uppermost in his mind were as follows. 1st. That a great deal of valuable time had already been uselessly lost by somebody, some how, no particulars being given. 2nd. Nobody knew exactly how or where the enemy’s line of battle ran & it was somebody’s duty to know. 3rd. That it now devolved on him personally to use up a lot more time to find out all about the enemy before we could move a peg. I remember thinking that the quickest & best way to find out about the enemy would be to move on them at once, but the old man seem to be feeling so real wicked, I concluded to retain my ideas exclusively in my own possession. And so off he went to the right, & we spent the whole day quietly & there was no fight at all in our front.”[6]

Sedgwick’s force escaped across the river the following night, leaving Lee more annoyed. He turned west again, planning to attack Hooker’s strong defensive lines. Once again, the Union divisions slipped out of Lee’s reach and retreated safely across the Rappahannock River. Finding the Union troops gone and reporting the news to Lee, General Pender got the recorded brunt of Lee’s anger: “General Pender! That is what you young men always do. You allow those people to get away.”[7]

Again, the newspapers praised Lee’s great victory at Chancellorsville. Again, Lee had won but failed to accomplish a destroying victory that could decisively help the Confederacy. He had won, but in his estimation, what did he have to show for it? The Army of the Potomac still existed. The war still continued. And thousands of his best troops and officers fell in the woods and fields around Chancellorsville.

Perhaps there is a tendency in some Civil War interpretation to point everything toward Gettysburg, and perhaps this is not always helpful. However, looking at Lee’s reactions in the two large battles prior to the Gettysburg Campaign may give stronger insight to his choices in Pennsylvania. Lee had been annoyed at Fredericksburg that he had not committed more of his ammunition and troop strength to the battle. At Chancellorsville, he had been twice angered that his enemy slipped away. Lee may not have wanted to fight at Gettysburg, but the Union army offered battle and under the circumstances, Lee decided to gamble for his crushing victory. However, just as Lee’s temperament and commitment changed over time, so had his opponents; the Union generals and soldiers in the summer of 1863 were a more experienced army than they had been the previous year. Lee attacked at Gettysburg and put in his available force…but it was not enough.

Lee was not a raging maniac controlled by his emotions, but he also was not the stately marble man without feeling or reaction. The visible annoyance at Fredericksburg and his “real wicked” attitude at Chancellorsville had impacts on those fights and on future campaigns. A different image of Lee starts to emerge from the pages of primary sources. And I am more intrigued by human, reacting Lee than by stately, ever-stoic Lee.

Sources:

Douglas Southall Freeman, R. E. Lee, A Biography, Volume 2, Volume 3 (New York: Scribner, 1934).

[1] Francis Augustin O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock (Baton Rogue: Louisiana State University Press), 452.

[2] Allen C. Guelzo, Robert E. Lee: A Life (New York: Knopf, 2021), 281.

[3] Ibid., 282.

[4] Richard A. Reinhart, “Robert E. Lee’s Medical History in Context of Heart Disease, Medical Education and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century” (Frederick: National Museum of Civil War Medicine, Surgeon’s Call, 2016) – https://www.civilwarmed.org/surgeons-call/lee/

[5] Allen C. Guelzo, Robert E. Lee: A Life (New York: Knopf, 2021), 281.

[6] Edward Porter Alexander, edited by Gary W. Gallagher, Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 213.

[7] Allen C. Guelzo, Robert E. Lee: A Life (New York: Knopf, 2021), 290.

Sarah, as it is the norm for you, a wonderful article about a very complex man, Robert E. Lee. I have recently finished Douglas Southall Freeman’s four volume biography of Lee and I was not only impressed with Lee’s wartime exploits, of course, but I was very inspired by Lee’s achievements both before the war as a brilliant civil engineer and his post war efforts to try to heal the war torn country and along with his educational reform work at Washington College in Lexington. Like I said, a very complex and thoroughly intriguing man.

As a tactician Lee was stately

but he was a traitor and undignified

But incredibly loyal to his state.

Tom

Perhaps the following observation from an unnamed historian is appropriate….”History is complicated. And history requires perspective and understanding, something sadly lacking in those who seek to erase history by imposing today’s standards of right and wrong.”

No offense but if Lee was a “traitor” for being loyal to his state against a centralized despotism, then so was our great Founding Father Washington WHO DID EXACTLY THE SAME THING!

Thank you for a very thoughtful article. I’ve heard it said that a person’s true identity emerges as they grow older and leave their primary career. The mask comes off, so to speak. If that’s true, Lee’s efforts in reconciliation and education postwar place him in a favorable light.

Like every person we study in history, Lee was the sum of many parts, both good and bad. We tend to identify the more positive traits as something which is to be emulated. When the historic figure is a military leader or political figure, we feel compelled to identify what made them great so we can apply to us or to today’s world. As time passes, we tend to forget that they were indeed human and probably had as many negative traits as positive traits. As you so well said, we always need to stop, dig a little deeper and develop a more complex picture of who they were in life. It doesn’t mean that we should throw them away because we found something negative. We just need to appreciate to whole person. History is made by flawed human beings.

Thank you. I’ve never studied Lee but gained the impression that he was a brilliant tactician. Apparently, I wasn’t the only one. Here are two quotes published in a 6 June 1864 “letter from Boston” in the Sacramento Daily Union. “I hope Grant will succeed, but Lee is a great General, and he will never give up!” “Richmond may be taken, but to take it will require the sacrifice of half our army!”

Another great one, Sarah! History remembers December 1862-May 1863 as the pinnacle of Lee’s career, but it’s enlightening to see that he probably didn’t see it that way. It’s also sort of fun to think of Lee as a grumpy old man saying things like, “Kids these days!” to officers like Pender.

I always felt that he learned great lessons both from the partial successes and failures of late 1862 through 1863. His health had seemingly stabilized by 1864, or else he had learned to deal with its limitations. His sense in allowing Longstreet to direct the counterattack at the Wilderness, his detailed position at North Anna and his hurriedly improvised one at Spotsylvania were worthy of a much younger, healthier man. He didn’t pull a Rosecrans and collapse when Grant/Meade ripped his center open at Spotsylvania; he inspired talented subordinates to rise to the occasion. And his counter punching South of the James continually frustrated Grant/Meade’s blundering attempts to maneuver the AoNV out of its trenches. I love the way Sarah refuses to go off track into the “Traitor, traitor, traitor!” Seidule Swamp, and sticks to a clearheaded military evaluation of this fierce, tortured, complex individual.

We forget, sitting in the comfort of our living rooms that living in the field for an extended period causes stress on the body in every way, from basic bodily functions to eating right, staying hydrated, to staying cool or warm for the season to writing letters, to every daily function. For us in the US army, spending days or weeks in the field, a simple hot (or cold – depending on the season) shower was like manna from heaven.

Tom

Excellent work, Sarah. Your balanced essay and emphasis on primary sources put you on a level with professional Ph.D. historians and far above those yapping “Traitor” at Lee’s heels.

Great article. The comments are predictable though. Reminds me that I need to read that Ty Seidule book.