Book Review: Confederate Privateer: The Life of John Yates Beall

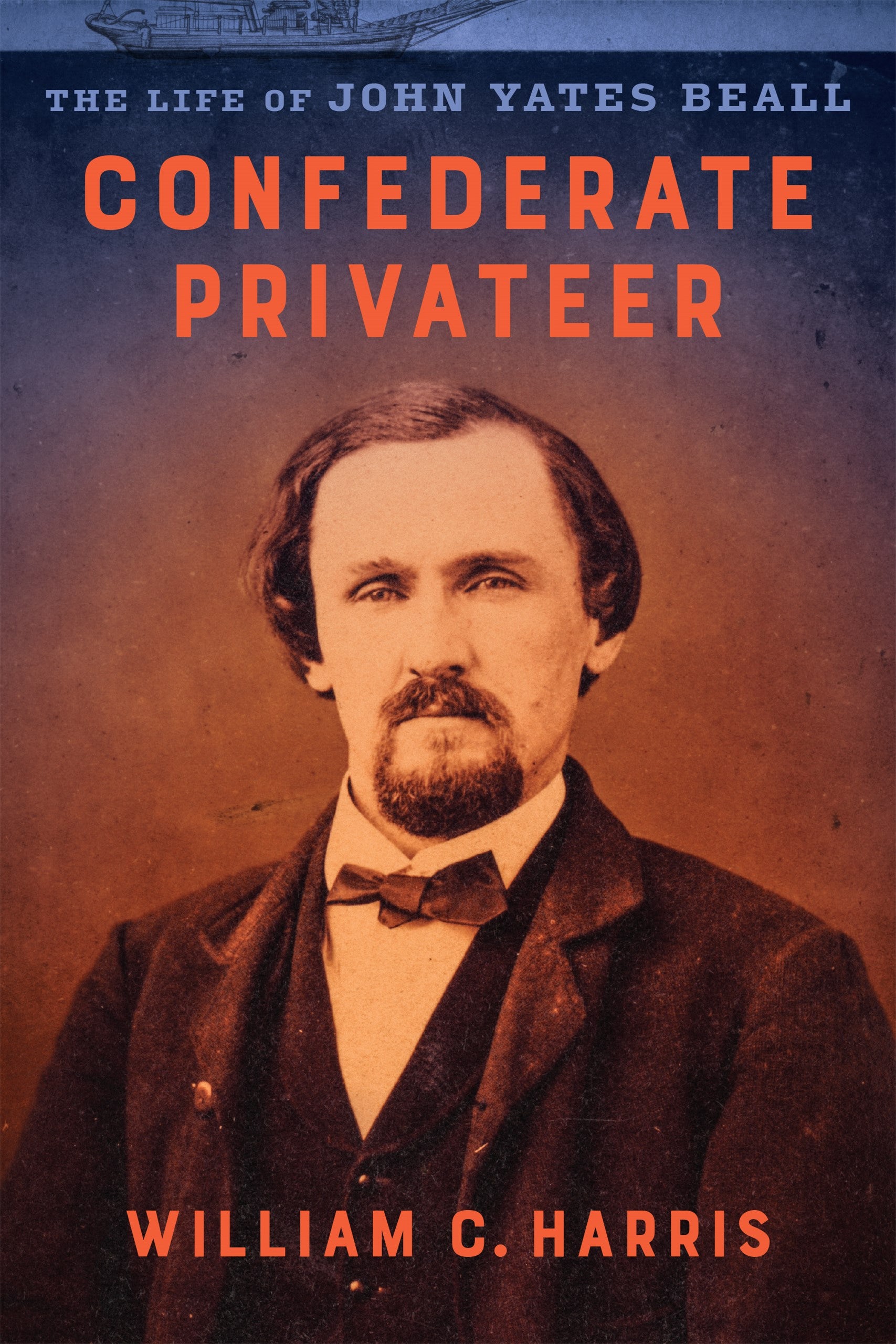

Confederate Privateer: The Life of John Yates Beall. By William C. Harris. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2023. Hardcover. 182 pp. $45.00.

Confederate Privateer: The Life of John Yates Beall. By William C. Harris. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2023. Hardcover. 182 pp. $45.00.

Reviewed by Gordon Berg

On February 24, 1865, at Fort Columbus on Governors Island in New York Harbor, John Yates Beall was hanged as a spy for doing what his revolutionary forefathers had done, operate through an official “letter of marque and reprisal.” It was the inglorious end to the short but swashbuckling life of the Confederacy’s least likely privateer. During his thirty years of life, Beall was a planter, soldier, naval officer, privateer, and commando. William C. Harris brings his exploits to life in a scholarly, yet lively, biography that follows the peripatetic Beall from Virginia to Florida to Iowa to Canada and finally, in February 1863, back to Virginia where he hoped to present to Confederate President Jefferson Davis two schemes to support the Confederate cause he had concocted during his travels.

His favorite plan, according to Harris, “called for a bold naval operation to free Confederate prisoners on Johnson Island off Lake Erie in Sandusky Bay, Ohio.” The other plan, Harris writes, “provided for a small force of privateers to attack Union merchant vessels in the Chesapeake Bay and its inlets.” Beall boldly planned to lead both operations even though he had no knowledge of seamanship or the sea. Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory nixed the Johnson Island scheme but did give Beall a commission as acting master in the Confederate Navy and the go-ahead for operations in the Chesapeake.

Harris makes extensive use of two sources to tell this part of Beall’s story. The first is a biographical fragment compiled from jottings from Beall’s diary and correspondence with his friend and college roommate Daniel B. Lucas. Lucas had it published privately in Montreal in 1865. The other is from W.W. Baker, a member of Beall’s privateering crew in the Chesapeake, and published in 1910 with an introduction by Douglas Southall Freeman. Harris skillfully meshes a plethora of primary and secondary sources to recreate Beall’s exploits into a narrative that reads like a Hollywood movie script.

Under manned and untrained, Beall commenced his operations in the Chesapeake Bay in July 1863. Early success, primarily the destruction of the Cape Charles lighthouse on Smith Island, made him the toast of Richmond society and sparked outrage in Washington, DC. A chance discovery by a fisherman of his sleeping band of merry marauders got Beall captured and sent to Fort McHenry in Baltimore harbor where, he was told, he would be tried as a pirate. Before his trial by a military commission, Beall was exchanged. While visiting his fiancé in Columbus, Georgia, Harris quotes Beall as writing, “I do not know that we ever accomplished any great things but we devilled [sic] the life out of the gunboats on the Chesapeake trying to catch us.”

While Beall was buccaneering around the Bay and visiting with his fiancé, Confederate Naval Secretary Stephen Mallory green-lighted his old Johnson Island scheme, albeit led by another commando. It failed. Beall hastened to Richmond and offered to give it a go. He made his way to Toronto and, in August 1864, teamed up with Jacob Thompson, the Confederacy’s secret service head in Canada. Harris vividly describes what can only be characterized as a “keystone cops-like” operation that also ended in failure. Beall avoided capture and returned to Toronto.

After a week of hunting in the wilds of northern Ontario to let the diplomatic dust settle, Beall came up with proposals for more outrageous operations. An increasingly enthusiastic Jacob Thompson was ready to listen and fund almost anything. This time, Harris’s cinematic-like narrative describes a plan for “freeing the prisoners on Johnston’s Island, and, with the captured U.S. gunboat [the USS Michigan], clearing the lakes of Union commercial shipping.” Not stopping there, Beall further proposed “creating havoc in the U.S. towns along the Lake Erie coast, beginning with Buffalo.” While these, and other ingenious plots, all failed, Beall had succeeded in becoming a wanted man on both sides of the northern border.

Undaunted, Thompson and Beall, again united, this time in Richmond, concocted perhaps their wildest scheme. It involved hijacking a Lake Shore Railroad train on December 15, 1864, purportedly carrying substantial amounts of gold and greenbacks plus seven Confederate generals from Johnson’s Island to Fort Lafayette in New York harbor. According to Harris, “Beall eagerly accepted the high-risk assignment.” That this plan failed should come as no surprise. What is surprising is that Beall’s hairbreadth escapes had finally run their course. A Niagara, New York policeman nabbed Beal while napping on the train and remanded him to the police headquarters jail in New York City.

Harris devotes the final third of his book to Beall’s trial by military tribunal and what he describes as the desperate efforts by Beall’s friends to save the Captain from the gallows. Like so much in Beall’s life, these efforts failed. Only the hangman succeeded. William C. Harris is also successful. He spins a fabulous yarn that Hollywood could not concoct, only proving once again that history can be stranger than fiction.

Gordon Berg has published dozens of articles and reviews in popular Civil War periodicals. He writes from Gaithersburg, Maryland.

I can’t imagine wintertime imprisonment on Johnson’s Island in Lake Erie north of Sandusky. I’m not sure how Beall thought he could succeed, but the Confederate POWs would have thanked him