Book Review: Longstreet: The Confederate General Who Defied the South

Longstreet: The Confederate General Who Defied the South. By Elizabeth R. Varon. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2023. Hardcover, 459 pp. $35.00.

Longstreet: The Confederate General Who Defied the South. By Elizabeth R. Varon. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2023. Hardcover, 459 pp. $35.00.

Reviewed by Andrew F. Lang

James Longstreet’s civil war did not end at Appomattox. For decades thereafter, the Confederacy’s Number Three—behind Jefferson Davis and R. E. Lee—battled the Civil War’s verdicts and its contested narratives of memory, including his own role in the conflict’s storied campaigns. Searching to exonerate their beloved Lee, Lost Cause authors hunted for a scapegoat whom they could blame for Confederate defeat. They found in Longstreet the perfect heel. He was a Georgian, not a Virginian. He defied Lee’s orders at Gettysburg, leading somehow to inevitable Confederate defeat. And most damnable of all, after the war he became a Republican, a vocal supporter of Reconstruction, a defender of Black suffrage, and a fierce critic of white southern intransigence.

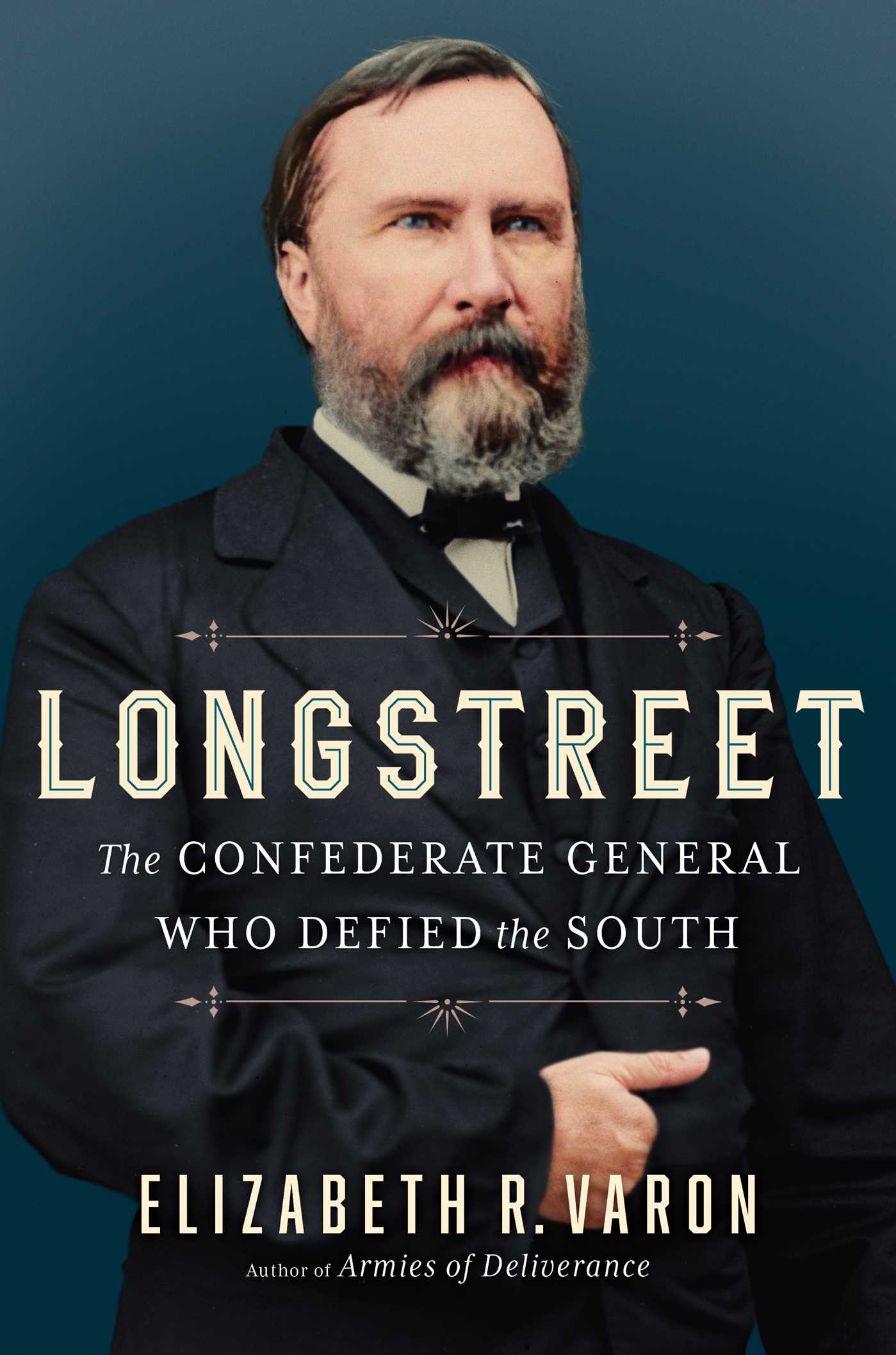

Elizabeth R. Varon’s brilliant biography confronts the decades-old conventional wisdom about Longstreet’s legacy. She poses a straightforward yet complex question: “How did Longstreet, a man who had gone to war in 1861 to destroy the Union and perpetuate slavery,” come to renounce all for which the Confederacy stood and champion a new postwar biracial order (xv)? The answer is found in the most striking of places: in the picture of Longstreet gracing the book’s dustjacket. There, we see the former Confederate not donning his general’s uniform, but rather his civilian dress. He gazes not backward to an idyllic past, but forward toward a better future.

Varon’s wonderful analysis reminds us that Longstreet dedicated much of his public life (he lived from 1821 to 1904) not in defending slavery or serving the Confederacy (though he had been a proslavery apologist and staunch Confederate). Varon offers a not-so-subtle cue that one’s life is not the sum-total of four years of war, much less several days spent on a battlefield at Gettysburg. That is why she dedicates two-thirds of her book to the years after 1865. And that is the way Longstreet would want it.

Though he long defended his military record, Longstreet came to repudiate the Confederacy. He insisted that his fellow white southerners abide the terms at Appomattox. Secession was dead, slavery was vanquished, emancipation was a reality. Those were all good things, Longstreet concluded. Confederates lost the war, he believed, not because of the Union’s industrial might or ranks overflowing with mad conscripts. Defeat came from simpler sources: ill-conceived military decisions and, as Varon puts it, Confederate “hubris” (305). Herein lay the wellspring of Lost Cause ire. Longstreet was a dissenting postwar voice in a region bound by rigid conformity. He embraced a new South liberated from the impossible grip of slaveholding genuflection. And he practiced what he preached, as custom surveyor in New Orleans appointed by his dear friend President Ulysses S. Grant; as an officer in the biracial Louisiana State Militia which he led against white paramilitary insurgents; as an active member of Georgia’s Republican Party; and as the United States minister to Turkey from 1880 to 1881. All the while, he advocated “radical” Republican Reconstruction policies, especially the Fifteenth Amendment and Black political equality.

With deft sensitivity, Varon implies that Reconstruction could have turned out very differently, that it was not doomed from its inception. Longstreet was proof of this. During the war to be sure, he was “sustained by his fervent ideological commitment to the Confederate cause” (28). However, in the long wake of Appomattox, he believed that dignified honor required all white southerners acquiescing to Abraham Lincoln’s vision for a “new birth of freedom.” Lincoln anticipated that with the death of slavery, white Americans would be liberated from their deceitful vanity about humanity, politics, nationhood. With remarkable humility, Longstreet took seriously the new way of things. He insisted that societies can change, that democracy is based on majority rule, minority consent, and grace for one’s fellow citizens. Here, Varon poses her most provocative inference of all: what might have happened had more former Confederates followed Longstreet’s postwar example?

Longstreet was the raw proof that change could have happened. He practiced the kind of “self-reinvention” that Union victory and emancipation necessitated (291). Yet purveyors of the Lost Cause insisted on ideological though fanciful purity. They aimed to destroy anyone who dissented. Longstreet welcomed the fight. “The most his southern critics treated him as an apostate on the issue of race,” Varon explains, “the more receptive he became to Republican ideology” (157). For more than two decades, he published popular articles and his massive memoirs, critiquing the Lost Cause, laying blame where he saw fit, defending biracial politics, and promoting sectional reconciliation. Longstreet was hardly a progressive and never perfect. His own complexity underscored the complexity of his era. And Varon’s triumphant book provides the vindication that he always sought.

Andrew F. Lang is associate professor of history at Mississippi State University. A recipient of the Society of Civil War Historians’ Tom Watson Brown Book Award and a finalist for the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize, he is now writing on the relationship between Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant.

Such a well crafted review Andrew, thanks. Varon shows how biographies can be important tools in understanding larger historical events like Reconstruction, not merely life stories within that context. Bravo!

Outstanding book. It is very informative and east to read. Highly recommended.

Thanks for this great review Andrew…I had been on the fence about whether I was going to read this, and this has tipped me over in favor!

I’m puzzled. The matter of Longstreet having completely fabricated the conversations he claimed he had with Robert Lee at Gettysburg has already been confirmed, so that doesn’t need to be addressed; nevertheless, he’s still worthy of a biography. But to claim Elizabeth R. Varon’s biography is “brilliant” when, as shown, she states, “How did Longstreet, a man who had gone to war in 1861 to destroy the Union and perpetuate slavery…”, is puzzling, for Longstreet went to war neither to destroy the Union – this was the purpose of no one in the Confederacy, nor of that entity as a whole – or to perpetuate slavery. Like 90%+ of his comrades, Longstreet went to war to protect his homeland – remember, slavery was practiced by and benefitted only 7% of the Confederacy’s population – and there was no intent to “destroy” or even damage the Union. This is misguided, pedantic, 21st Century CRT revisionist history of the Civil War and the Confederacy. In other words, it is not factual, or legitimate history. Let’s suppose that Lincoln made the right choice, and did not make war on the Confederacy. Three things would have happened: The Union, as personified by the states that remained in it, would have survived and prospered, not been destroyed; the Confederacy within a generation would have eliminated slavery; the Confederacy would have, by 1900, unanimously chosen to rejoin the Union. A biography of Longstreet, or any other similar man, could be a brilliant work if it tells the truth about his life, but it cannot be brilliant if it gets completely wrong the man’s reasons for leaving the country of his birth to become a citizen of a different country and then fights to defend that country. Moreover, if Varon takes seriously Longstreet’s false claims of trying to talk Robert Lee out of his tactical decisions at Gettysburg, this would also disqualify it as being a “brilliant” biography. It would be perfectly fine – preferred, in fact – if a biographer truthfully debunked Longstreet’s claims, yet still wrote a biography of an accomplished and courageous if deeply flawed man. But it can never be brilliant to get wrong, for the sake of ideology, the most important event in said man’s life. That would be like claiming “Mao Tse-Tung engaged in the Chinese Communist revolution in order to free his fellow Chinese and bring them a better life” when he did no such thing; he did it so he could be the next Emperor of China and enslave the then 800 million people in the country – 100 million of whom, by the way, he had murdered between 1949-1976 in order to consolidate and cement his hold over the country.

It is refreshing to read something (your thoughtful response) beyond the current narratives about the civil war and nearly everything else in our moment in time and you have done an admirable job of explaining the simplistic, reductionist and usually false story of the antebellum south and Longstreet’s mythical status as an evil man made good. The review, and assumedly the book, suffer from the fallacious belief of our modern times – a historical figure is grotesque and not worth discussing until inner reflection redeems him. In this case, Longstreet is a racist tool of oppression who was redeemed by his own reconciliation with race, a now enlightened, liberal man who is acceptable… “Longstreet was hardly a progressive and never perfect”. I sincerely love good biographies, but in the current era our chattering class of professors and writers mostly genuflect at the altar of what they would like reality to be rather than what it is. And strangely, Lang’s point about the south’s racial purity motivation seems perfectly analogous to today’s adherence to progressive puritanism. You are either progressive and good or needing redemption.

I agree that had we not committed to war, extreme poverty and triangulation of white southerners would likely have ended the slavery stain from the south in the decades following the war era. Beyond that though, it’s impossible to ignore a century of government directed oppression of blacks before the Civil Rights Act; Longstreet’s defense of reconciliation and inclusion of both races in the public square are noble. But I am equally ambivalent about the north’s supposed greatness given the squalor and subjugation blacks faced in the north post civil war particularly in cities with strong unions. Nobel white virtue in northern cities today bespeaks paternalism and soft bigotry and lacks true historicity.

A well written correction to the all too common misconception of the War Between the States. I will add to your excellent summary the suggestion that to the extent the war was about slavery it was about how slavery would end, not whether it would end. Looking back 160 years later, I’m inclined to think that it ended in the worst way possible. The worst way for everyone, including (and especially) the slaves themselves.

Southern society was of course not without its flaws, as is true of every society in this fallen world. But I believe that a large part of the blame for how tragically things turned out can be laid on the shoulders of certain people of the North, from those whose agitations starting around the 1830s actually reversed the declining prospects of slavery in the South and precipitated its resurgence, to those who after the war used the former slaves as a tool in their pursuit of vengeance and political power to oppress and crush a society that had already suffered unspeakable loss and was entirely at their non-existent mercy.

The injustices of Jim Crow were in my view a sinful response to a malicious attack from the North. I don’t seek to justify that period, and I rejoice that it finally ended. But to assign it to Southern prejudice or ignorance is to exhibit those very things oneself. Men like Gordon and Forest (the latter no doubt to the surprise of many) urged reconciliation in sincere and felicitous tones, while at the same time not shrinking one bit from calling out the malicious empire builders from the North for what they were doing. It’s a shame that Longstreet could not strike the same balance, but I suppose the blame for that lies not only with him.

By definition, secession would destroy the union. The primary reason the North (the Union) waged war on the south was to preserve/restore the union. Breaking the union of states into two countries, by definition, would have destroyed this union. As for the three assumptions of Mr. Schafer,, that “The Union,…would have survived and prospered, not been destroyed; the Confederacy within a generation would have eliminated slavery; the Confederacy would have, by 1900, unanimously chosen to rejoin the Union,” are only assumpti0ns, which Mr. Schafer seems to assume as fact. It’s possible to see the north (the Union) as surviving economically, but prosperity would be less probable. The south did secede because of slavery (as expressed in their own articles of secession in various states), and wanted to “spread the gospel” of slavery to export it to territories where it was not practiced (or legal). So it’s hard to simply assume that the Confederacy would have eliminated slavery, especially within a generation. And the unanimous decision of the southern states to rejoin the Union, while possible, is an assumption that is very weak on evidence. The Union fought, at first, to preserve the Union, which the south had determined to break up. The south fought, first of all, for the preservation of slavery, then for the south’s convenient understanding of state’s rights, then to preserve their homeland. The Union’s pivot to embrace a second war aim came first as a military strategy, then as a social and moral mandate. I’m looking forward to reading this book!

I love the ongoing effort to make angels out of humans, at the expense of the South. Varon’s argument is based on the assumption that favoring the North at any point in this history was a good idea, a sad dismissal of a great many relevant facts. Too much has been made of Longstreet’s advice at Gettysburg; it was an unworkable idea that would have resulted in the annihilation of the ANV, rather than the outcome of at least an organized and successful retreat; the reasons it was unworkable were immediately evident and not vigorously contested. Whether annihilation and a quick end to the War was Longstreet’s goal has been discussed, but never proven. The South was aware that Longstreet was related to Julia Dent, Grant’s wife, and that they had long been acquainted in the military, but that was true of a number of Southern/Northern officers. It was his post-War wholesale embrace of the North at a time when repressive retaliation – mainly aimed at keeping tariff levels high – was being inflicted on the South that incensed its defeated population, which was not overly interested in being nice at that point. Perhaps Longstreet saw it as a way to get capital investment into the South, but he certainly misread his audience. But keep it up – maybe there will be a nice article on RE Lee, who did also advise a measured approach to defeat, and met with Northern capitalists in his few years after the War.

Agreed. Longsteet’s favorite guy was Longstreet. And Lee achieved far more with silence than Longstreet blowing off his please-my-politicians ballyhoo.

Sounds like those wanting a bio focused on Longstreet’s Civil War career should read Jeffry Wert’s bio while those wanting a focus on his post-war life should read the Varon bio.

Anybody who believes Longstreet–the consummate liar and opportunist–would want a “bi-racial order” is not after the truth. Also, he’d be unique in his time indeed, since even Abolitionists did not champion this, let alone ex-Confederates.

You have been misinformed. The white north was pure and desperately wanted complete equality…right?

I have this book and plan on reading it.

That said, the proof is in the pudding and the former Confederates didn’t change as Longstreet did. Why? Because as Americans living in a constitutional republic, and the war of rebellion being a sunk political cost, they weren’t going to have the Federal government do as it pleased with them election over election. The idea that southern Democrats would let a Republican controlled Washington do that for half-century or more is ridiculous.

Longstreet charted his on course and did well by it. Praise be to him. I applaud his independence of mind and his ability to fight alongside his black neighbors against white supremacy. However, I think it is naive to think it was possible for many more ex-Confederates (besides maybe a Mahone, Beauregard, and some others) to travel alongside him as postbellum Republican politicos. That what if is a castle in a sky.

If anyone has read the book, can you tell me this-

Does Varon adequately show and engage what Longstreet’s true intentions were when he wrote his 1867 letters to the New Orleans press?

Nice review. I look forward to reading the book. I hope the commenters on this post take the time to read it as well.

Agreed but you would be hard pressed to find a more knowledgeable group of aficianados capable of gleaning the overarching viewpoint of a book on the history of an event/events than those who imbibe in civil war writings.