Book Review: Abolitionist of the Most Dangerous Kind: James Montgomery and His War on Slavery

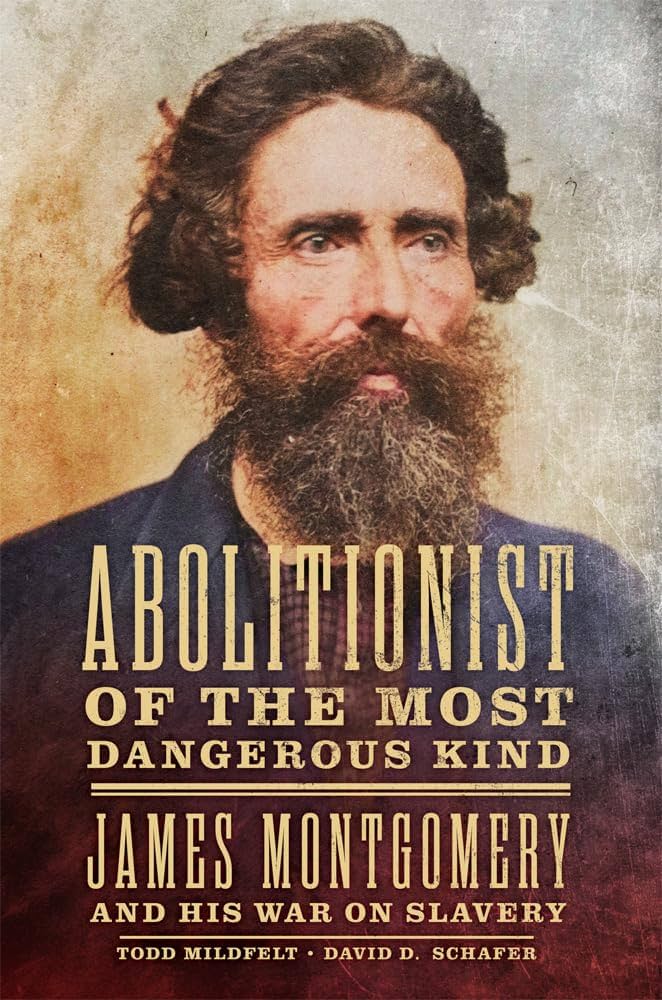

Abolitionist of the Most Dangerous Kind: James Montgomery and His War on Slavery. By Todd Mildfelt and David D. Schafer. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2023. Hardcover, 406 pp. $45.00.

Abolitionist of the Most Dangerous Kind: James Montgomery and His War on Slavery. By Todd Mildfelt and David D. Schafer. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2023. Hardcover, 406 pp. $45.00.

Reviewed by Tim Talbott

In their Abolitionist of the Most Dangerous Kind: James Montgomery and His War on Slavery, the most recent biography of the Kansas jayhawker and Civil War colonel, co-authors Todd Mildfelt and David D. Schafer seemingly leave no primary source stone unturned in providing an exciting and exhaustive account of this man’s life. In doing so, they show that Montgomery was a much more complicated personality than the one briefly depicted in the 1989 motion picture Glory.

Born in Ashtabula County, in northeastern Ohio, in 1814, Montgomery came of age in a region that was still largely frontier. Ohio, after all, achieved its statehood only a little more than a decade before his birth. The toughening difficulties he encountered growing up served him well throughout his life, which later produced significant personal struggles. In addition, coming of age in an area rapidly populating by westward migrating New Englanders, who brought their anti-slavery and abolitionist sentiments with them, likely had a latent influence on young Montgomery.

At age 22, James relocated to Kentucky and married into a slaveholding family. Widowed by age 30, he soon remarried, and in 1852 moved his growing family to Missouri. The authors contend that a motivating factor in migrating was that “Montgomery became frustrated by the need to compete against slave labor.” (16) Another move two years later landed the Montgomery family in Linn County, Kansas Territory.

In discussing this part of Montgomery’s life, the authors supply abundant contextual information for readers to better comprehend the volatile situation on the Missouri/Kansas border, which in turn helps frame Montgomery’s evolution into a militant jayhawker. It appears that Montgomery’s motivation to align with the Kansas Free State cause at this phase of his life was his concerns over slavery’s detrimental effect on poor whites. However, when pro-slavery Missourians flooded the territory and utilized intimidation tactics and violence in order to discourage Free State proponents from settling in Kansas, Montgomery, along with others, fought back.

The spring and summer of 1856 brought about a number of events that turned up the heat on the slavery issue in Kansas and publicized its happenings to the rest of the United States. On May 21, pro-slavery Missourians sacked Lawrence, Kansas, a town perceived as an abolitionist hotbed in the territory. The following day, in Washington D.C., South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks assaulted Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts over a previous speech against slavery in Kansas. Then, two days after Brooks caned Sumner, John Brown and several other Free State associates murdered five pro-slavery men in Kansas. Skirmishes between the two belligerent sides broke out at Black Jack in June and Osawatomie in August.

As things cooled down during the brief administration of territorial governor John W. Geary, they soon heated back up with President James Buchanan’s support of the Lecompton Constitution, the territory’s proslavery constitution. Montgomery appeared to radicalize during this period. Tired of talk, he and others sought action to settle the issue once and for all.

Mildfelt and Schafer do a wonderful job of clearly explaining the territory’s convoluted story. They offer a true telling about the events that Montgomery, Charles Jennison, and others got involved with in their efforts to make sure Kansas remained free and by taking their war into Missouri, freeing enslaved people, and driving enslavers out of Kansas.

By 1861, with Kansas now in the Union as a free state and with a civil war raging, Montgomery first served as colonel of the 3rd Kansas Infantry. In this role he and his regiment of predominantly anti-slavery soldiers raided into Missouri, freeing enslaved people. As the authors suggest, Montgomery’s regiment was rather unique for United States forces at this time: “From day one, Montgomery’s men were fighting a different war—a war for freedom of the enslaved.” (131) Jayhawking writ large.

In early 1862, Montgomery lost his command during a reorganization of Kansas troops. Hoping to lead a Black Kansas regiment under the auspices of the Militia Act of 1862, Montgomery did not get his wish. However, Montgomery’s lobbying efforts eventually ended with him receiving command of the 2nd South Carolina Colored Infantry. Leading this regiment, and serving alongside the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry, brought Montgomery praise and criticism, successes and failures.

After Montgomery castigated members of the 54th Massachusetts in a racist speech for not accepting their unequal pay, some of the criticism came from his own soldiers. The authors do an excellent job of explaining Montgomery’s contradictory abolitionist actions and this bigoted rant. Not allowing Montgomery a pass, they offer their insightful interpretation of this unseemly event.

In the fall of 1864, bad health prompted Montgomery to return home to Kansas where he recuperated and went on to fight yet more battles commanding a state militia unit until the war’s end. He ministered to a Seventh Day Adventist congregation before dying in 1871.

James Montgomery was a complex man, who lived a complicated life during a trying time in American history. Abolitionist of a Most Dangerous Kind tells Montgomery’s life story, warts and all, in a way readers will appreciate. Richly illustrated with period images, photographs, and excellent maps, it is sure to be the definitive biography of Montgomery for years to come.

thanks Tim … i assume this is the same Col. Montgomery from the movie Glory … the character in the film is certainly an odd duck.

Yeah…Glory is literally mentioned in the first paragraph.

oops.

As a novice scholar of “All Heroes Ohio” (John Brown, Custer, Sherman, Grant, McKinley, Garfield, etc.) I am so pleased to discover James Montgomery is a native of the Buckeye State, too! I always have been sceptical of his treatment in “Glory,” and after learning more about him in the amazing tome, “John Brown 50 Years After,” I now must have a hard copy of this exceedingly exciting book! Compounded by my 30-plus years as a Southern Baptist minister, I’m really ready to read about this man, another “inspirational Christian fanatic” from Ohio. Amen?