Book Review: Southern Black Women and Their Struggle for Freedom during the Civil War and Reconstruction

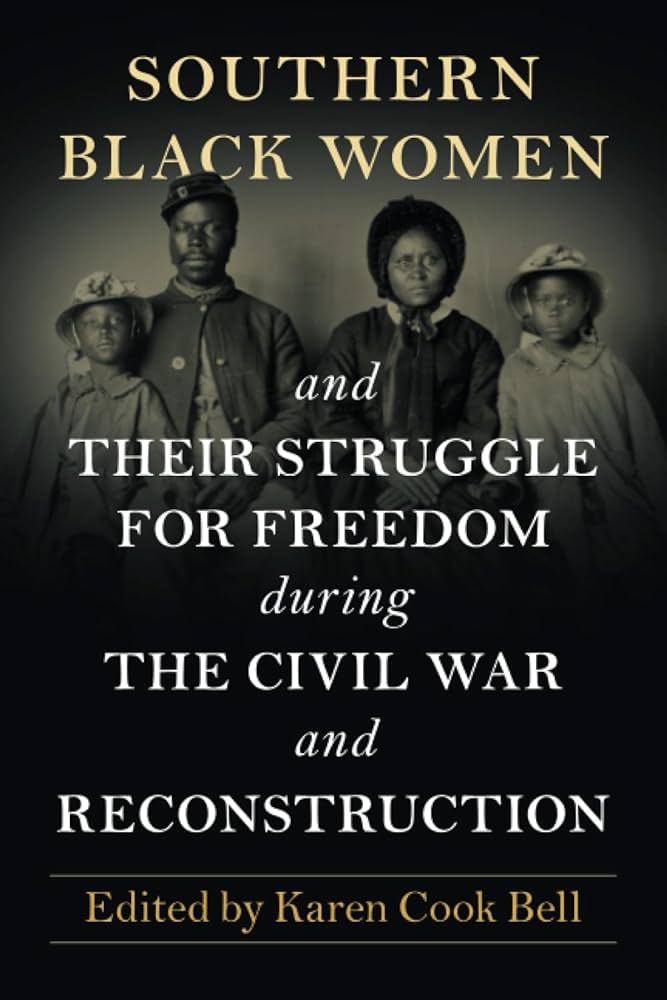

Southern Black Women and Their Struggle for Freedom during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Edited by Karen Cook Bell. London: Cambridge University Press, 2023. Softcover, 244 pp. $29.99.

Southern Black Women and Their Struggle for Freedom during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Edited by Karen Cook Bell. London: Cambridge University Press, 2023. Softcover, 244 pp. $29.99.

Reviewed by Sheritta Bitikofer

The historiography of African American women in the nineteenth century has blossomed in recent decades, leading to a greater understanding of the complex relationship between race, gender, and society. Scholars have built upon the foundational work of historians who made important connections—and sometimes discovered glaring ideological contradictions—between the nature of womanhood and the experiences of Black women in America, both enslaved and free. In Southern Black Women and Their Struggle for Freedom during the Civil War and Reconstruction, edited by Karen Cook Bell, several scholars contribute their valuable insights into how formerly enslaved African American women navigated the uncertain waters of life as free individuals.

The participating historians draw heavily on primary source documentation, both directly from the women of the period themselves or through official court records. These sources shed light on their different challenges and how they used what resources were at their disposal to live their interpretation of freedom for themselves and their families. The compilation is divided into three sections with three chapters each. The first covers emancipation in relation to African American women’s labor, the second examines the all too real experience of gender violence during the era, and the concluding section discusses the African American family unit and how emancipation impacted their livelihoods. Appreciatively, each chapter explores these topics in different parts of the South and analyzes the varied experiences of Black women in different regions, since not all of the South experienced the war and Reconstruction in the same way.

The first two chapters, written by Katherine Chilton and Arlisha Norwood, respectively, detail the ways in which Black women exercised their newfound independence through their choice of labor. No longer forced to stay on plantations or work for their former enslavers, Black women could choose how they earned money for themselves and for their families. While Chilton focuses primarily on married Black women in the District of Columbia, Norwood’s contribution focuses on single Black women in Virginia and their pursuit of employment. A common thread between both pieces was how formerly enslaved women utilized the federal government and various organizations available to them in order to find work, as well as establish their rights as free laborers, going so far as to seek justice against unfair employers in the Freedman’s Bureau courts.

In the third chapter of this section, Felicia Jamison writes about the fascinating subject of personal property and possessions amongst emancipated Black women. She goes into detail showing how these women were active members in their local economy, even during enslavement. Jamison also discusses the various ways in which they accrued assets in the form of personal possessions that assisted them in freedom, as well as the importance of leaving generational wealth for their children. As with the previous authors, Jamison drew upon court records for her evidence, as Black women petitioned for compensation during the war. These women actively advocated for themselves throughout the decades and into post-Reconstruction, defining how their labor, time, and money aided in their vision of freedom.

The second section of the book is vitally important to understanding the transition from enslavement to freedom for Black women in the context of access to their bodies. As enslaved women, their bodies—specifically their ability to reproduce—were not their own. Sex and reproduction, in essence, was part of the labor they provided for their enslavers. Additionally, Southern society did not view Black women in the same way as White women. They were not naturally virtuous or considered respectable, given their status as property.

In freedom, Black women saw their opportunity to rewrite the narrative and claim the rights as any other woman brutalized by a man, regardless of their color or former status as enslaved or free. They sought recourse against Union soldiers—both White and Black—for sexual harassment and rape. As the women in the previous section, they used the fullest extent of military law—utilizing an aspect of the Leiber Code—to define what it meant for them to be fully free in body and spirit. Crystal Feimster writes on this subject and how it played into the mutiny of Fort Jackson in Louisiana, and Kaisha Esty covers the subject of sexual consent throughout Union-occupied territories. The only departure from this theme is Karen Bell’s contribution, which lends more to the topics within the first section. It discusses how Black women asserted their right to wages and fair employment practices, and how the presence of the Union army in Louisiana and Southern Georgia impacted self-emancipating women behind Union lines.

In the final section, the historians zoom out from the focus of women to encompass the entire family unit and its responses to freedom. Kelly Houston Jones presents a microstudy of post-emancipation realities for Black families in Little Rock, Arkansas, a location far removed from the main theater of war and one that is often overlooked. She details the subtle changes of labor, habitation, and military service amongst Black families in Little Rock from before the war and through Reconstruction. She also highlights the ways in which Black women moved through the public sphere, covertly expressing themselves in local politics through their involvement in their communities.

Brandi C. Brimmer, too, investigates the ways in which slavery laws in North Carolina complicated the emancipated lives of Black women and their families. More specifically, she targets how notions of marriage and widowhood conflicted with their eligibility for benefits, and how their community reacted to other racially-based injustices like indentured servitude and the apprenticeship of Black children.

Finally, Hilary Green takes the reader down to the Deep South to Mobile, Alabama and tells the story of Emerson Normal School. For many African Americans, freedom meant the chance to educate themselves and their children. In order to do so, they needed competent teachers, preferably those of their own race. Green stresses the perceived importance of education amongst the Black community in Mobile, and their determination to fight against racial prejudice within the public and private school systems of the South.

Southern Black Women offers significant historical analysis on the labor, bodies, and family matters of emancipated women during and after the Civil War. Each author is extremely well versed in their chosen topic and grounds their findings in primary source documentation, much of which may have previously been untapped by other historians in the field. They also rely on the foundational works of other historians who came before them. This important book presents new and intriguing information about how Black women viewed themselves and the society around them, expressed through their decisions as they lived out their definition of freedom.

Thanks Sherrita, great review … and an interesting reference to use of the Lieber Code.