The West Point Effect: Duty, Honor, and Second Chances

ECW welcomes back guest author Dan Walker

“American” from the start: West Point’s “Eggnog Riot”

From its start, the United States Military Academy at West Point was something of a paradox: It was, and needed to be, a place of order, discipline, and obedience; but America’s founding principles emphasized individuality and, where compliance was necessary, the voluntary kind. This potential conflict didn’t keep the school from turning out well-trained military leaders, but these were American leaders, not Prussians.

In fact, others have observed that the value of a West Point education—before the Civil War, at least—derived less from military-specific training than from more general education for a variety of knowledge and skills.[1] A few examples from the experience of America’s citizen-soldiers, both at school and later at war, may help illustrate.

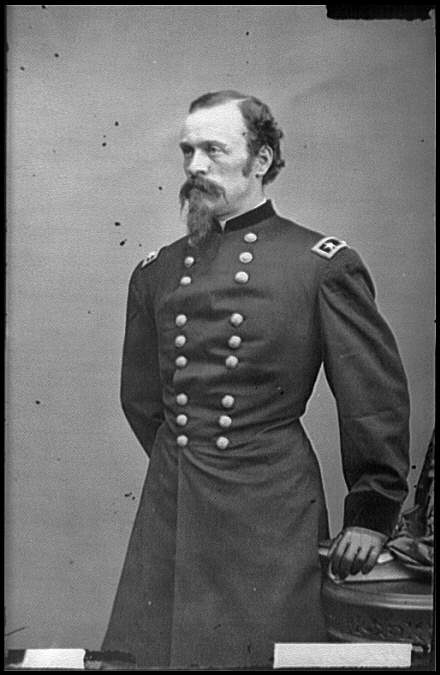

One cadet-turned-wartime leader was Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Class of 1828, who served as a U. S. army lieutenant and eventually secretary of war. His own history provides a case-study of America’s resistance to strict accountability. For example, consider the Great Eggnog Riot of 1826.[2]

The event was an upshot of Superintendent Silvanus Thayer’s effort to impose discipline, part of which was to outlaw liquor. Christmas and the Fourth of July had been exceptions, but this Christmas, after an outbreak of drunkenness on the Fourth, all “spirituous drinks” had been banned. Cadet Davis had already been court-martialed for drunkenness on the Fourth, though reinstated on appeal by President John Quincy Adams. Now he had learned of a highly “spirituous” Christmas Eve eggnog party, maybe even helped organize it, but soon heard that the commandant, Captain Ethan Allen Hitchcock, had also heard and was on his way.[3]

Did Cadet Davis, having learned his lesson in July, keep his head down and his hands clean? No, he did not. Instead he burst into the party, shouting “Put away the grog, boys!” But the commandant was already there. He ordered everyone to quarters and then returned to his own. Orders, however, were ignored, and things got worse. Shots were fired, rocks and logs thrown around, bonfires lit, windows broken, and instructors threatened. Nineteen cadets were court-martialed and fifty-three others disciplined—almost a third of the cadet corps. All of the nineteen were convicted, but President Adams gave clemency to seven of them. Davis was not even punished, though he had been in on the planning and is said to have consumed plenty of nog, mostly because he had returned to his room and stayed there.[4]

Examples of this resistance to accountability can be found throughout West Point’s pre-Civil War history. In 1839 Superintendent Richard Delafield complained that in one year all nineteen of his expulsions had been commuted by the War Department.[5] Such leniency also bothered cadets. One, James H. Wilson, later a major general in the Union Army, was outraged that in the two years he knew about (he graduated in 1860) all those dismissed had been reinstated by the secretary of war.[6]

When failure is an option:

And there were other kinds of failure. One was academic, which often seemed rooted in social class. Cadet Davis, after all, was the son of a Mississippi cotton planter who sent him to a Catholic prep school.[7] Almost from its start there were efforts to keep the academy from being a club for the elites—especially during the Jacksonians’ assault on “privilege”[8] —whose fortunate sons came with a long head start.

In part to mitigate this lead, candidates were nominated by state political leaders. Thus, nominees might be members of an educated elite, but they might also be the sons of important (if untutored) constituents—say, prominent landowners—whose sons might have had only a few years in a common school. Entrance exams were often simple and perfunctory, mocked by both students and instructors. The bar seems to have been kept low so that “common” boys did at least have a shot. After all, a young man with little academic aptitude might make a fine officer. Cadet Thomas J. (later “Stonewall”) Jackson comes to mind. He would, of course, have to pass his courses, and many did not. The failure rate was often high in the first year.[9] So here was a second chance for leniency. Most of the nineteen Delafield had tried to expel had failed too many classes. But, as with the Eggnog Riot, there were exceptions, second chances, and clemencies.

One equalizing factor is worth noting: All cadets graduated with solid training in mathematics and engineering. So it’s ironic that the school survived the Jacksonian onslaught mostly by producing not just officers, which a peacetime army barely had room for, but engineers, which the growing country really needed.[10]

Cultural tension goes to war:

Returning to our question about Cadet Davis: Does leniency at the academy seem to have influenced wartime leadership? A good case study is the treatment of desertion, which plagued both Union and Confederate armies. By one estimate compiled by Ella Lonn in 1928,[11] one in nine Union soldiers deserted, as compared to one in seven Confederates.

How did Confederate States President Davis respond? He issued at least two proclamations that amounted to general offers of amnesty. In one such order, issued in 1863, after a lengthy appeal to patriotism, Davis wrote this:

…I grant a general pardon and amnesty to all officers and men within the Confederacy, now absent without leave, who shall, with the least possible delay, return to their proper posts of duty, but no excuse will be received for any delay beyond twenty days after the first publication of this proclamation….[12]

So, an excuse might be “received” for any absence, of any length, so long as it didn’t last longer than twenty additional days? Davis’s leniency should not surprise us, in view of his early experience as a beneficiary.[13] But such leniency extended well beyond the West Pointers. For example, Zebulon Vance—a planter, lawyer, and Confederate colonel—when elected governor of North Carolina in 1862, went to work right away to deal with the desertion problem by, on the one hand, sending out the militia to arrest absentees, while, on the other hand, issuing a proclamation promising amnesty to those who returned to the ranks in two weeks—or else![14]

More and more extreme punishments and incentives were tried on both sides, but the plague of desertion was never stamped out.[15]

Even the famously strict General Robert E. Lee, a pre-war West Point superintendent, was loath to apply the ultimate penalty (capital punishment) until the fall of 1863.[16] Lee once explained the citizen-soldier dilemma to his Third Corps commander, General A.P. Hill, who wanted to press charges against one of his brigadier generals for an unpardonable blunder: “These men are not an army,” said Lee, as overheard by a junior aide. “They are citizens defending their country. General Wright is not a soldier; he’s a lawyer. … I have to make the best of what I have.” Besides, Lee asked, “Whom would you put in his place?”[17]

Lee probably spoke for many other American leaders, then or later.

Was desertion less of a problem for later U.S. armies? Maybe so, but by one study reported in the New York Times there were 50,000 deserters from U.S. armed forces in World War II, but only 49 were sentenced to death and only one was actually executed.[18]

Whatever else America’s future military leaders learned at West Point in its first fifty years, many of them seem to have preserved an American faith in the redeemable nature of the common citizen. On reflection, that’s probably a good thing.

[1] Morrison, James L., Jr. (Oct., 1974) “Educating the Civil War Generals: West Point, 1833-1861.” Military Affairs, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 108-111. https://doi.org/10.2307/1987111

[2] Agnew, James B. (1979). Eggnog Riot: The Christmas Mutiny at West Point. Presidio Press.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ambrose, Stephen E. (1966) Duty, Honor, Country: A History of West Point. Johns Hopkins University Press.

[6] Longacre, Edward G. (1972). Grant’s Cavalryman: The Life and Wars of General James H. Wilson. The Stackpole Company.

[7] Cooper, William J. (2000). Jefferson Davis, American. Knopf.

[8] Ambrose, Op. cit.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ambrose, Op. cit.

[11] Lonn, Ella (1928). Desertion During the Civil War. American Historical Association. Reprinted 1998, University of Nebraska Press.

[12]“Jefferson Davis’s Address,” August 1, 1863. In Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, Documents and Narratives, Vol. 7. Frank Moore, Editor. Doc. 113. Accessed from Perseus Digital Library 4.0. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, Editor-in-Chief. Accessed at: https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc= Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0042%3Achapter%3D115

[13] Ambrose, Op. cit.

[14] Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series I, Vol. XVIII, 860-61.

[15] Lonn, Op. cit.

[16] Weitz, Mark A. (2008). More Damning than Slaughter: Desertion in the Confederate Army. University of Nebraska Press.

[17] Freeman, D. S. (1935) R. E. Lee: A Biography. Vol. 3, p. 331.

[18] Garner, Dwight (2013) “Into the Lives of Three Deserters Who Did Not Have a Good War,” New York Times, June 9, 2013. Retrieved at: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/10/books/the-deserters-a-world-war-ii-history-by-charles-glass.html#:~:text= Nearly%2050%2C000%20American%20and%20100%2C000,in%20the%20war%20much%20longer.

thanks Dan … great essay about the military academy and some familar West Point names — i had no idea that Davis was such a “bad boy”

I saw just yesterday that the Academy is changing its motto and slogan. No more “Duty, Honor, Country”.

I shudder to think which three words our ‘leaders’ select to replace them.

To be accurate, the USMA is not changing its motto. It will remain “Duty, Honor, Country.’ Those words, however, will be replaced in the school’s Mission Statement with “Army Values.”