Gettysburg Off the Beaten Path: The Acheson Rock

Just north of Little Round Top, amidst a grove of trees, lies a boulder with a simple inscription on it: “D.A. 140 P.V.” That stands for David Acheson, 140th Pennsylvania Volunteers. The boulder served as Acheson’s temporary grave until his family arrived to retrieve his body on July 15, 1863. However, it also served as a makeshift memorial to Acheson in the years following the battle.

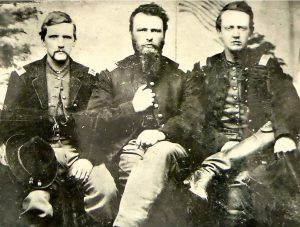

David Acheson was born in January 1841 in Washington County, Pennsylvania to Judge Alexander Wilson Acheson and his wife Jane. He attended Washington College (now Washington & Jefferson College) where he garnered the reputation as “one of the most promising young men” of his class. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Acheson rushed to enlist in a three-month regiment, but was mustered out in August without seeing any action. But when President Abraham Lincoln issued a call for 300,000 more volunteers in 1862, Acheson not only answered it, but helped recruit a company of soldiers for the 140th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Popular among his peers, young Acheson was elected captain of Company C.[1]

The regiment was initially assigned to guard duty along the North Central Railway in Maryland, but it joined the II Corps of the Union Army of the Potomac just after the Fredericksburg campaign. Thus, Acheson and his comrades saw their first fighting at the battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. “It was terrific the way in which the shell and shot flew around us,” he wrote to his mother after the battle. “We came off better than I expected.”[2]

After licking its wounds from Chancellorsville, the 140th Pennsylvania broke camp and began its march northward in pursuit of the Confederate army on June 15, 1863. “Our marches are very fatiqueing [sic] indeed and several times when it was raining the men at the end of a day’s march would lie down in the water and sleep soundly,” the 22-year-old captain wrote. “I never knew what a man was able to endure before.”[3] On June 28, the regiment arrived at the Monocacy Junction just south of Frederick, Maryland. Acheson devoted that evening to write what would be his final letter to his mother. “I hope this is but the beginning of a final defeat to the rebs,” Acheson reflected. “I believe this to be the campaign of the war, and the rebs have staked their all upon it.”[4]

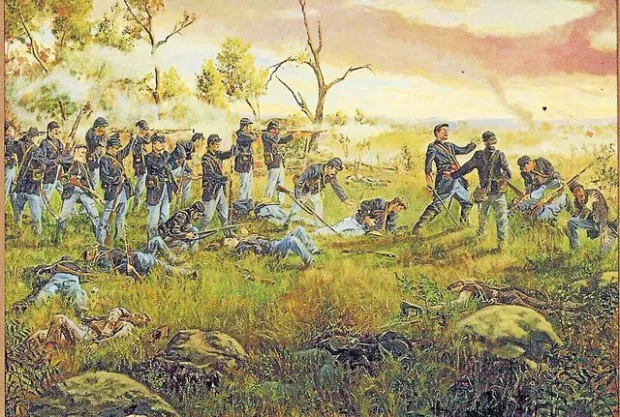

Three days later on July 1, a courier galloped along the ranks of the 140th Pennsylvania and informed them that two Union infantry corps had engaged the enemy at Gettysburg. The II Corps commenced a forced march until they arrived on the battlefield at 2 am on July 2. There, the regiment waited for much of the day until fighting began on the Union army’s left flank. As Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles’ line collapsed in the Wheatfield, the 140th Pennsylvania and its division advanced to plug the gaps. “As we came nearer to the scene of the conflict it became evident that our closely pressed troops were gradually falling back, and our pace was accelerated to double quick,” the regimental historian recalled.[5] When the men reached the edge of the Wheatfield, they received a deadly volley from the Confederates, from which their brigade commander Brig. Gen. Samuel Zook fell mortally wounded.[6]

As the division swept across the Wheatfield, the 140th Pennsylvania, located on the extreme right of the line, skirted its western edge. Acheson and his men engaged the enemy in a close-quarters fight, pushing through the rocky and wooded terrain. When they reached the crest of the Stony Hill, the men let loose “ringing cheers,” having driven the enemy. However, the regiment now confronted the “continuous blaze of light” produced by a long line of Confederate muskets to their front and right. The Pennsylvanians hurriedly returned fire, but Acheson’s company C—outflanked and exposed on open ground—suffered the most casualties. Colonel Richard P. Roberts fell mortally wounded during the fray, along with Lt. Isaac Vance, one of Acheson’s close friends. Acheson was shot twice in the chest just a few yards away and was probably killed instantly.[7]

The regiment’s poor position compelled them to fall back and abandon Acheson’s body, at least temporarily. Company C suffered 32 casualties of its 38 men in its fight on the Stony Hill—with seven dead, 22 wounded, and three captured. Members of the 140th Pennsylvania made several failed attempts to retrieve Acheson’s body from the Stony Hill on July 3 and 4. Even two officers of the 155th Pennsylvania, who had been Acheson’s classmates at Washington College, joined the search. Each attempt to retrieve the body was met by a harassing fire from Confederates who still occupied the Stony Hill.[8]

Finally on the morning of July 5, after the Confederates had withdrawn from the field, men of the 140th Pennsylvania succeeded in locating their captain’s body. A small band of soldiers carried Acheson approximately a half mile across the Wheatfield to a nearby woodlot, just south of the George Weikert farm. There they buried him in front of a small boulder, which they marked by carving Acheson’s initials: “D. A.”

News of the young captain’s death reached Washington County soon after. On July 14, Acheson’s relatives traveled to Gettysburg to retrieve his body from its shallow grave. He was buried in Washington Cemetery the following day, where his tombstone bears an inscription of the 23rd Psalm: “Yea though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for thou art with me.” Five years later, an unknown member of Company C returned to Acheson’s former gravesite at Gettysburg and added the letters “140 P.V.” to the existing carving.

To Reach the Acheson Rock:

-Drive south on Baltimore Street.

-Bear right onto Steinwehr Avenue.

-Follow Steinwehr Avenue for 2 miles (which becomes the Emmitsburg Road).

-Turn left onto the Wheatfield Road.

-Follow the Wheatfield Road for 1 mile and park on the shoulder of the road.

-Exit your vehicle and walk down the farm lane to your left. You should encounter a small farm to your front. This is the John T. Weikert farm, constructed after the battle in the 1870s.

-As you approach the buildings, walk directly between the house and barn. Then, turn to your left and follow a small path around the edge of the woods.

-Follow the path as it curves to the right into the woods. The Acheson Rock sits on the right side of the trail. When you reach the horse trail, you have gone too far.

PLEASE NOTE THAT THE JOHN T. WEIKERT FARM IS PRIVATE PROPERTY. PLEASE RESPECT THE OWNERS’ PRIVACY AND DO NOT KNOCK ON THE DOOR AND ASK THEM TO TOUR THE HOME.

[1] Robert Laird Stewart, History of the One Hundred and Fortieth Reigment Pennsylvania Volunteers (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Regimental Association, 1912), 6-7.

[2] Jane M. Fulcher, Family Letters in a Civil War Century: Acheson, Wilsons, Brownsons, Wisharts, and others of Washington, Pennsylvania (Avella, Pennsylvania: Quality Quick Printing and Copy Center, 1986), 378.

[3] Fulcher, Family Letters in a Civil War Century, 382.

[4] Fulcher, Family Letters in a Civil War Century, 382.

[5] Stewart, History of the One Hundred and Fortieth Reigment Pennsylvania Volunteers, 102.

[6] Stewart, History of the One Hundred and Fortieth Reigment Pennsylvania Volunteers, 104.

[7] Stewart, History of the One Hundred and Fortieth Reigment Pennsylvania Volunteers, 104-105.

[8] Stewart, History of the One Hundred and Fortieth Reigment Pennsylvania Volunteers, 125.

Well done post, appreciate the research. But you need to fix your directions because parking on Wheatfield Road is ILLEGAL. Cars can turn right onto Crawford Avenue, park there and walk back.

Thanks for the tip

Nicely done. I will definitely look for this piece of history next time I’m in Gettysburg.

Excellent post. Thank you.