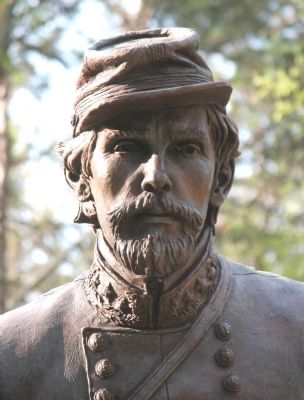

Patrick Cleburne at Shiloh or How to Learn Your Trade on the Fly, Part II

By later afternoon, both William Tecumseh Sherman and John McClernand had seen their divisions get forced back again and again. They were becoming tired and dispirited. C. Carroll Marsh wrote that his brigade had “been reduced to a mere nominal one.” Andrew Hickenlooper of the 5th Ohio Battery observed that “While there was no direct evidence of a panic, they appeared to be impressed with the idea that they had played their last card, and further effort would be unavailing. Singly and in squads they were walking away, regardless of the threats and pleadings of their officers, who were finally forced to give orders to retire.” The regiments were mixed. James Veatch formed an ad hoc brigade made up of his own 14th Illinois and 25th Indiana, along with the 7th, 29th, and 52nd Illinois. By 4:00 p.m. the divisions were aligned along good ground near Perry, Cavalry, and Mulberry Field. They only faced a few batteries, regiments of cavalry, and brigades led by Cleburne and Preston Pond, neither commanding every regiment in their brigade. If Sherman and McClernand could repulse any Confederates, it was this paltry force.

Under orders to attack, William J. Hardee, commanding the Rebel left, gamely pushed his men. The cavalry made some ineffective attacks and Preston Pond launched his 1,000 men into Cavalry Field, but under protest. They were shredded, losing around 300. Cleburne, with the 5th, 23rd, and 24th Tennessee and 15th Arkansas, moved through wooded terrain that masked his approach. Abraham M. Hare’s brigade drove in Cleburne’s skirmishers. However, Hare’s men were running low on ammunition and were disorganized. Robert Sturgess of the 8th Illinois reported, “The company officers lost control of their men from the promiscuous mingling together of the different regiments.” Hare ordered a retreat, but the 18th Illinois advanced, found itself in a crossfire, and then fled in what one member admitted was “Some of the Tallest Running that we Ever Done.” In Cleburne’s words, “the enemy gave way.” In the retreat, Hare was wounded twice; he never again saw combat.

By then, Pond had struck and was turned back. Despite his failure, it still unnerved some Federals and came as more men fleeing the “Hornets Nest” moved through the lines with tales of horror. To McClernand’s shock, the line “was irresistibly swept back by the tide of fugitive soldiers and trains vainly seeking security at the landing.” In this chaos, Cleburne next struck the 7th, 29th, and 52nd Illinois and swept them up. Veatch was planning to attack with the 14th Illinois and 25th Indiana, but both were hit. William Camm of the 14th Illinois recalled, “in an instant the air seemed full of bullets.” The battered regiment had already lost seventeen officers killed and wounded, and another two went down. They collapsed. John Foster, commander of the 25th Indiana, wrote that just then men “came sweeping by us in utter and total confusion — cavalry, ambulances, artillery, and thousands of infantry, all in one mass, while the enemy were following closely in pursuit, at the same time throwing grape, canister, and shells thick and fast among them.” In the maelstrom of fleeing men and Rebel bullets, Veatch had to abandon his horse and had a second killed. Veatch tried to hold a second position but fell back yet again.

Cleburne’s men were low on ammunition, and McClernand patched together a new line at Chambers Field. However, Ulysses S. Grant’s last line was weakest around Chambers Field, with only two cannon from the 5th Ohio Battery present and without the protection from the Dill Branch and Tilghman Creek ravines to its east and west, respectively. Cleburne may not have been strong enough to breach it, but so far the Union had failed to halt his command for any prolonged length of time, and the Rebels had taken few losses.

Cleburne might have caused the Federals further problems at Chambers Field. Even then, though, there were no brigades close at hand to support Cleburne. Veatch described how “a wide gap had occurred beyond McClernand’s left, but the rebels did not seem anxious to enter this open door to the landing…It was my impression then, as it is now, that any time after two o’clock, while they were making such tremendous attacks on the right and left, a division of six or eight thousand men might have forced its way through the gap and reached the landing in spite of us.” Among the Confederate’s lost opportunities on April 6, perhaps one of the most crucial was that Cleburne attacked unsupported.

Cleburne did advance on Grant’s last line, but not at Dill Branch. He halted as his men came under artillery fire. None died, but some fell over at the shock of the heavy cannon sported by the gunboats. Cleburne next had William Harder take a company of the 23rd Tennessee through a gap. They fired on and silenced the 5th Ohio Battery, only to come under heavy fire themselves. Harder thought there was a chance to attack and gain the Union rear. Cleburne rode off to get permission from Hardee only to be told to retire. Generally, most Confederates were glad or at least accepted the order to retreat. Only after April 7 did they turn P.G.T. Beauregard’s order into a fatal mistake. However, it seems Cleburne and Harder were not among them. Cleburne remarked that “root tape would take us to hell yet.” Cleburne’s Irish accent would surface in times of stress and Harder had to admit “I did not no what he meant.”

Hardee later thought Cleburne came within 400 yards of Pittsburg Landing and victory. Yet, it is unlikely Cleburne could have burst Grant’s last line open. There were still not any Confederates nearby, and the sun was fast setting. It is possible with more time the Confederates might have exploited the weak point Cleburne discovered, although given the command chaos, that is not assured. All that could be said is on the afternoon of April 6 Cleburne took 800 men and used them to devastating effect against the Federals and showed a tactical finesse he did not exhibit only a few hours before.

The rest of Shiloh was just as eventful for Cleburne. His men spent the night in Benjamin Prentiss’ old camp. Many ran off to Corinth with loot, a point that embarrassed Cleburne. The gunboats fired all night, and Cleburne observed that the shells killed mostly Union wounded who were resting on the ground. He thought “History records few instances of more reckless inhumanity than this,” a rare emotional moment in Cleburne’s Shiloh report.

On April 7 Cleburne gamely readied his command. He would find himself southeast of Jones Field, confronting Stephen Hurlbut’s division. His sector was commanded by Braxton Bragg, and ever aggressive, he ordered Cleburne to attack. Cleburne protested, but did the best he could. He placed his men in a valley to avoid cannon fire, while Isadore P. Girardey’s Washington Artillery banged away at the Federals until running low on ammunition.

The undergrowth broke up Cleburne’s advance, and he could not see much of his battle line. Cleburne considered the ensuing contest one of the “severest conflicts” of the battle. John Osborn, commanding the 31st Indiana, observed, “The attack was fiercely made and bravely resisted by our men.” McClernand then dispatched regiments to Hurlbut’s aid, and Cleburne’s men scattered. Only the 15th Arkansas, Cleburne’s old command, rallied near what Cleburne called “the scene of the disaster.” Cleburne attached stragglers from other commands and made a quick charge that threw the Union into some disorder, boasting “The enemy fled back faster than they came.” Cleburne though, had only fifty-eight men and two of his regiment commanders had fallen. Cleburne withdrew, his brigade no longer a functional battle unit. He spent the rest of April 7 rallying troops in the rear. Regardless, April 7 showed Cleburne doing well in a tough situation. He saw the attack was a likely failure, but did all he could to make it work. He made good use of terrain and made sure a nearby battery supported him.

After Shiloh, Cleburne spent weeks examining his disastrous attack on Sherman’s division. He also no doubt considered what worked in his attack on the afternoon of April 6 and what went wrong on April 7. After Shiloh, Cleburne emphasized drill and discipline, having seen the effects of straggling. Cleburne also made good use of terrain in his future battles, after utterly failing to do so in his April 6 morning attack. He also formed elite sharpshooter companies to give his brigade greater tactical flexiblity. That Cleburne learned these lessons after Shiloh was impressive; many of his colleagues North and South never did. All the more impressive, Cleburne seemed to grasp the lessons only hours after his assault on Sherman. Even fewer commanders showed that kind of awareness in the heat of battle.

Very good post, thank you Sean