America’s Greatest Chess Player Was a Confederate?

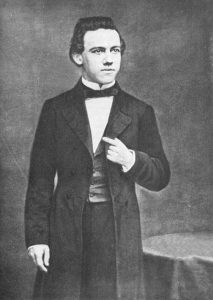

Few names shine as brightly as Paul Morphy’s in the annals of chess history. Known during his time as the greatest living player of the game, Morphy stepped out upon the world stage by winning the American Chess Congress in 1857. Yet, amidst his meteoric rise to prominence in the mid-19th century, a lesser-known chapter of his life intertwines with the Civil War.

Paul Charles Morphy was born in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1837 to a family of prominence and wealth. His father, Alonzo Morphy, cultivated an illustrious legal career and held positions as a Louisiana state legislator, Attorney General, and a Louisiana State Supreme Court Justice. Morphy’s childhood was emblematic of Southern aristocratic life in the Antebellum Period. His prodigious French Creole mother entertained the family with a variety of instruments while men of the household played board games like draughts or chess.[1]

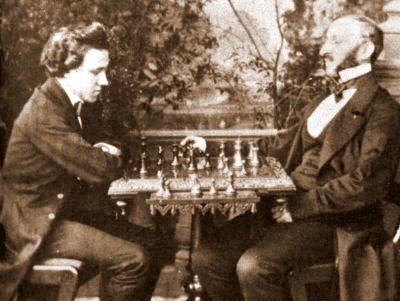

Historians differ on when and how Morphy learned the game. However, his uncle allegedly testified that the young prodigy learned how to play entirely on his own—simply by observing his father and uncle play one another. However, some chess scholars denounce this story as apocryphal. Regardless, the nine-year-old Morphy advanced to become one of the best players in New Orleans by 1846. That same year, General Winfield Scott arrived in Louisiana after the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, pausing briefly in New Orleans on his way to take command of the army in Mexico. The future Civil War general enjoyed a good game of chess and requested to face the best player in the city. Louisiana Supreme Court Justice George Eustis made arrangements for the general to play Morphy after a reception and dinner. However, Scott (who considered himself a competent player) was offended when a nine-year-old approached the board. The general only agreed to play after Justice Eustis and other dignitaries assured him that Morphy was indeed the best player in New Orleans. The child defeated Scott in two games, the first in ten moves and the second in only six.[2]

While Scott went on to accomplish victory in Mexico, Morphy achieved his own glory on the chess board. He defeated Hungarian chess master Johann Löwenthal in 1850 and easily won the First American Chess Congress in 1857. In between victories, he attended the University of Louisiana and studied law. Though Morphy dominated American chess, his skills were yet to be tested against the world’s greatest players—most of whom resided in Europe. So the young prodigy travelled there in 1858 to face household names like Adolf Anderssen and Daniel Harrwitz. In England and France, Morphy played simultaneous exhibitions against eight players, sometimes while blindfolded.[3]

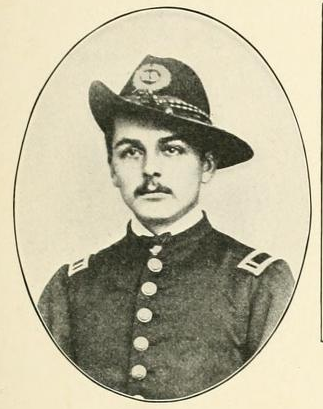

But storm clouds began gathering over America during Morphy’s European escapade. The prodigy returned home just in time to witness his native state secede from the Union on January 26, 1861. As young men flocked to recruiting stations, Morphy’s allegiances appear to have been divided. “Without doubt he was torn between his loyalty to the Union and to the state of Louisiana,” his biographer David Lawson writes. Morphy’s brother Edward promptly enlisted in the 7th Louisiana Regiment, but the twenty-three-year-old chess prodigy was not as eager. Regardless, Morphy travelled to Richmond in 1861 to offer his services to the Confederate cause and play a few games of chess. “The arrival of the noted player excited, even at that troublous time, a keen interest among the lovers of the kingly game,” recalled the president of the State Chess Association of Virginia. [4]

At some point during his visit to Richmond, Morphy likely joined the staff of Confederate General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. The Morphys and Beauregards were well-acquainted members of Louisiana high society, and therefore Morphy’s appointment to the general’s staff is unsurprising. While no documentation affirms Morphy in this role, numerous contemporary accounts refer to him as a Confederate staff officer, including Gilbert Frith, the president of the State Chess Association of Virginia. Other eyewitness accounts claim to have spotted Morphy at Beauregard’s side during the First Battle of Manassas, though this has never been confirmed. The general allegedly removed Morphy from his staff after noticing the young man’s lack of enthusiasm for the Confederate cause.[5]

His sojourn in the Confederate army completed, Morphy returned to New Orleans during its occupation by Federal troops. Sergeant George Haven Putnam, a Union soldier serving under General Nathaniel P. Banks, recorded a chance encounter with Morphy in New Orleans in January 1863. “A friend in one of the New England, also a chess player, pointed out to me one day crossing Carondelet Street the figure of Morphy,” the soldier later wrote. Putnam, a lifelong fan of the game, found himself awestruck at the site of one of its legends. Moreover, he also particularly admired Morphy’s revulsion to the Confederate cause. “He remained, therefore, between the two great war parties, sympathizing with neither and exposed to the loneliness that must always come to the ‘in-between’ man,” Putnam mused. “Remaining in his home city, he was exposed to the criticisms and gibes of the older men whose sons had gone to the front and of the girls of society who had no patience with a Louisianan who would not fight for the pelican flag.”[6]

Perhaps in an effort to escape this loneliness, Morphy followed his mother and sister to Paris where he continued to play chess. He visited Cuba in 1864 and played against the celebrated champion Celso Golmayo Zúpide in what would become one of the prodigy’s last serious matches. But as the war raged, so too waned Morphy’s interest in the game. “We are all following with intense anxiety the fortunes of the tremendous conflict now raging beyond the Atlantic, for upon the issue depends our all in life,” he wrote a friend in 1863, perhaps referring to his family’s wealth and property. “Under such circumstances you will readily understand that I should feel little disposed to engage in the objectless strife of the chess board.” Then, he added that his time interest chess had all but “frittered away”. This sobering conclusion as a result of the war is surprising, given Morphy’s divided loyalties. But perhaps the Morphys’ front seat to the American Civil War constituted enough for the young player to recognize chess as “only a sport.”[7]

After the war, Morphy returned to New Orleans to finally kickstart his law career. But his practice largely failed, since the young man had garnered reputation as a world-renowned chess player and not a world-renowned lawyer. Near the end of his life, Morphy began suffering bouts of depression that prompted his mother to try to admit him to a Catholic sanitarium. He successfully denied her and also rebuked the pleas of his family and friends to return to professional chess. Past his prime as a world class player and now a failed attorney, Paul Morphy died in 1884 at the age of 47, likely from a stroke.[8]

An unenthusiastic Confederate, Morphy stands out as an individual who’s career was impacted by the Civil War in a unique way. Unlike his friends and family who embodied Southern patriotism, Morphy appears to have been a lost soul during the conflict, lacking strong political convictions and robbed of his true sense of purpose: chess.

[1] David Lawson, Paul Morphy: The Pride and Sorrow of Chess, (Lafayette, LA: University of Louisiana Press, 1976), 10-11.

[2] Lawson, Paul Morphy, 10-14.

[3] Frederick Milnes Edge, The Exploits and Triumphs in Europe of Paul Morphy, the Chess Champion, (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1859), 16; Lawson, Paul Morphy, 125-134.

[4] Lawson, Paul Morphy, 267-269.

[5] Sean Michael Chick, Dreams of Victory: General P.G.T. Beauregard in the Civil War, (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie LLC, 2022), 38; Lawson, Paul Morphy, 268-269.

[6] George Haven Putnam, Memories of a Publisher, 1865-1915, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1915), 30-31; Lason, Paul Morphy, 270.

[7] Lawson, Paul Morphy, 275.

[8] Lawson, Paul Morphy, 303-307.

Thanks, this was interesting. Also, thanks for the article on Prospect Hall, where Meade assumed command of the Army of the Potomac. I had always wondered where it was located and with your directions, I was able to visit it recently.

Glad you enjoyed it. And glad my directions were successful!

Serving in the field does require some enthusiasm. The lack of cleanliness, uncertain meals, lack of sleep, etc. wears some folks down. As a young lieutenant, we were assigned a new commander who had been Infantry in his distant past. But, more recently, he had been a general’s aid and a staff officer. Our first trip to the field, he completely fell apart. I recall him leaning against a wall, hiding really, looking just completely done in, asking me if I wasn’t tired? I suppose I said yes, but probably with some enthusiasm. He just looked away and we never saw him again that weekend in the field.

Tom

I’m sure it certainly takes a special kind of person.

The classic Morphy games show amazing combinations and open boards. He understood getting your pieces into the action quickly. A good theoretical match would have been Morphy against “Get there fustest with the mostest” Forrest, although I can’t say Forrest knew the game. What a nice article. To beat a general in 6 moves, like to see that one. Thanks.

Forrest v. Morphy would certainly be interesting! If I’m not mistaken, Morphy’s strategy included sacrificing a great number pieces, too.

I live in the French Quarter and used to give tours where we walked by Morphy’s grave in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1.

At Shiloh on April 7 Beauregard was confused when the Federals attacked and said this: “This is one of Morph[y]’s blind games. I wish I had him here to help me play it out.”

That’s an awesome connection!