Fate’s Cruel Timing: Sgt. Maj. George F. Polley, 10th Massachusetts Infantry

Sgt. Maj. George F. Polley seemed to be living a charmed life as a Civil War soldier at the beginning of the Petersburg Campaign. After joining up as a private in Springfield with Company C of the 10th Massachusetts Infantry in June of 1861, he had somehow avoided deadly camp diseases, battlefield wounds, and prisoner of war camps during his three year enlistment. He was only about 24 years old in the summer of 1864.

Unfortunately, not much is known about Polley’s life before his service commitment. Alfred Roe’s regimental history states that he was born in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, in the Berkshire Mountains. The 1850 census shows Polley as a nine-year-old living in the household of his parents Frederick and Harriet, along with an older sister and two younger brothers. The 1860 census indicates that Polley was no longer living at home and that he worked as an “operative” of some sort in Williamsburg, Hampshire County, Massachusetts, in the west-central part of the Bay State. However, Roe’s history also claims that Polley was a “silver plater” before enlisting. The census lists Polley as owning no real estate or personal property wealth; certainly not unusual for a then 19-year-old.

During the war, Polley and the 10th Massachusetts certainly saw their fair share of hard fighting in the Army of the Potomac. The 10th, a Sixth Corps regiment, fought in the Peninsula Campaign, the Seven Days’ Battles, Fredericksburg, Second Fredericksburg and Salem Church, The Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse, and Cold Harbor. He apparently proved to be an effective soldier as he received promotions to corporal (August 1862), sergeant (November 1862), first sergeant (January 1863), and sergeant major (February 1863). While many of his comrades chose to let their enlistments expire, receive their honorable discharges, and return home, Polley promptly reenlisted early as a Veteran Volunteer. In doing so he received a thirty-five day furlough.

As Federal forces in the Second, Fifth, Ninth, and Eighteenth Corps targeted and then assaulted the Confederate defenses of Petersburg, apparently Polley had some premonition of his fate. After those first days of hard fighting east of the Cockade City (June 15-18), things started to settle down on that part of line.

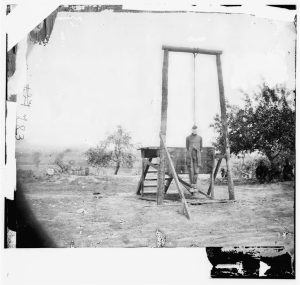

During the brief quiet period between that First Offensive and the next (June 22-23), the Federals hanged a soldier in the 23rd United States Colored Infantry named William Johnson, who had been arrested and convicted for desertion and an “attempt to outrage the person of a young lady at New-Kent Courthouse [Virginia].” The sight selected for the execution was near the Jordan House, which places it very near where the Petersburg National Battlefield visitor center stands today. According to Civil War photography historian, William A. Frassanito, both photographer Timothy O’Sullivan and one of Matthew Brady’s photographers captured the moment.

On the morning of June 20, the gallows stood awaiting its victim when the Confederates opened an artillery barrage. Some sources contend that the Confederate cannons were responding to a Federal battery near the scene of the hanging. Other indicate that the Confederates thought the Federals were hanging a Southern spy within eyesight of their lines, so they lobed a few projectiles in that direction. Regardless, one of the shells struck Sgt. Maj. Polley, who was attending the hanging with his regiment, in the abdomen. Polley died almost instantly.

Just before the tragic incident, the 10th Massachusetts had been notified that it was relived of duties and were awaiting orders to head to City Point and transports for the trip home. Several versions of Polley’s mortal wounding and his premonition of death exist.

Alfred Roe’s 1909 regimental history of the 10th Massachusetts mentions that Polley took the down time before the execution to amuse himself by self-inscribing a headboard, which included the incomplete death date of “June__, 1864,” while chatting for a last time with his comrades whom had not reenlisted and were getting ready to head home to Massachusetts. As mentioned above, Polley had signed up as a veteran volunteer, and unknown to him, a lieutenant’s commission was on its way. Polley was soon thereafter struck by the shell that killed him. A comrade searched for the carved headboard to use at Polley’s hastily dug grave, but soon learned that Polley had split it up minutes before he was hit to use as fuel to boil his morning coffee. The history says that William Winter from Company F carved Polley a new headboard, which was placed on his grave at the City Point hospital cemetery, where his body was taken as the members of the 10th Massachusetts went there to board transportation home.

Another history, this one written by Capt. Joseph Keith Newell and published in a diary style format in 1875, states: “MONDAY, June 20. As we were waiting to receive the necessary order to report to Massachusetts, the enemy opened a battery of twenty-pound guns from the opposite bank of the Appomattox, and shelled the Regiment vigorously for some time. Sergeant-Major George F. Polley was struck with one of the missiles, and almost instantly killed. The death of Polley cast a gloom over the home ward trip, which was commenced that day. By gallant conduct and fearlessness, he had become a favorite with the whole Regiment.”

The Roe regimental history story is partly corroborated by the diary of then Lt. Elisha Hunt Rhodes. Rhodes’s 2nd Rhode Island Infantry served in the same brigade as Sgt. Maj. Polley’s 10th Massachusetts. On June 20, 1864, Rhodes noted in his diary: “The 10th Mass. Vols. go home today their three years having expired. This leaves only the 2nd R. I. Veterans and the 37th Mass. Regiment left of the old Brigade. Yesterday Sergeant Major George F. Polley, 10th Mass. Col. showed me a board on which he had carved his name, date, of birth and had left a place for the date of his death. He had re-enlisted and was expecting a commission as Lieutenant in the 37th Mass. Vols. I asked him if he expected to be killed and he said no, and that he had made his head board only for fun. Today he was killed by a shell fired from a Rebel Battery.”

Yet another account of Polley’s death comes from the pen of Col. Oliver Edwards, who commanded the Fourth Brigade, Second Division, Sixth Corps, which included Polley’s 10th Massachusetts. Edwards’s details vary somewhat, like the others. As he remembered the incident, “It was at the close of a charge upon the enemy’s lines.” After sheltering under a slight rise from the Confederate “grape and canister,” his regiments went prone and awaited darkness. The enlistments of the 10th Massachusetts Infantry expired the next day and they were set to march to City Point the next morning. “Sergt. Maj. George F. Polly [sic] at this time carved upon a shingle, or slab, his own headboard, as follows: ‘Sergt. Maj. George F. Polly, 10th Mass. Vols. Killed at Petersburg, Va., June 21, 1864.’” As shown above, a couple of other accounts state that Polley left his death date blank. Edwards continued, “He handed the headboard to a comrade and insisted that he would be killed the next day.” This part of Edwards’s story does not match with Rhodes’s version, who explained that Polley told him he carved the board in fun. Edwards says that Polly’s regiment was “marched to the rear of Sugar Loaf Hill, and halted to draw rations.” Per Edwards, “On top of the hill two negroes were on a scaffold to be executed for rape.” Most accounts of the hanging only include Pvt. William Johnson as the victim. The rest of Edwards’s account matches that of the others, but adds that “He [Polley] was the only man hit, and that, too, in a position where he seemed perfectly safe.” Edwards closed claiming that “Any member of the brave 10th Mass. then present can vouch for the truth of the above.”

Regardless of the exact details, a soldier who probably should have lived was now dead. But all too often war creates such situations.

Polley’s service records show that the to-be-delivered commission was actually for his officer’s promotion to become a first lieutenant in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry, which along with the famous 54th Massachusetts, and 5th Massachusetts Cavalry, were the Bay State’s African American regiments. Obviously it is not certain that had if Polley not been killed on June 20, 1864, at Petersburg, that he would have survived the difficult battle at Honey Hill, South Carolina, with the 55th Massachusetts on November 30, 1864; or that he would not have fallen victim to a camp disease or some random accident. However, the timing of Polley’s death was particularly cruel, coming at time when many of his comrades were heading home and he would be going to a new regiment and leadership opportunities.

Those soldiers that had reenlisted from the 10th Massachusetts received transfers to the ranks of the 37th Massachusetts Infantry in Edwards’s Brigade, Wheaton’s Division of the VI Corps. They would fight in the Shenandoah Valley, breakthrough the Confederate defenses at Petersburg on April 2, 1865, battle at Sailor’s Creek on April 6, and be present at Appomattox Courthouse for Lee’s surrender to Grant on April 9.

Sources:

1850 Census, via Fold3.com, accessed May 7, 2024.

1860 Census, via Fold3.com, accessed May 7, 2024.

Compiled Military Service Record for George F. Polley, 10th Massachusetts Infantry, via Fold3.com, accessed May 9, 2024.

W. C. King and W. P. Derby. Camp-Fire Sketches and Battle-Field Echoes of the Rebellion. Springfield: King, Richardson, and Company, 1888.

William A. Frassanito. Grant and Lee: The Virginia Campaigns, 1864-1865. New York: Scribners, 1983.

Joseph Keith Newell. “Ours.” Annals of 10th Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers, in the Rebellion. Springfield: C. A. Nichols and Company, 1875.

Alfred S. Roe. The Tenth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1864: A Western Massachusetts Regiment. Springfield: Tenth Regiment Veteran Association, 1909.

Great article Tim. It’s so valuable to raise awareness of these personal stories; the trials and tribulations of everyday life as a common soldier in the Civil War.