Chancellorsville’s ‘Flying Dutchmen’ — Fact or Fable?

ECW welcomes back guest author Dan Walker.

After Confederate Lt. Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson’s devastating May 2, 1863, flank attack at Chancellorsville, a story soon spread throughout the Union army about the “Flying Dutchmen” of the heavily German XI Corps. Some of these soldiers fled far and fast enough to be captured by Confederates on the other end of the battlefield. Modern literature often repeats the story, but it’s hard to confirm.

The moniker spread quickly. As early as May 18, Union Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams wrote his daughter about seeing a staff officer firing his pistol at “some flying Dutchman.”[1] In his 1865 memoir, Union veteran Henry Black reported “officers of other corps made themselves speechless by striving to rally the ‘flying Dutchman.’”[2] Black, however, reports the “flight” was actually stopped by the Rappahannock River, well behind Union lines.

Some runaways must have gotten as far as United States Ford because Francis Walker—on Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps divisional staff—was in a hospital there that evening. In his memoir Walker reported, “Some of the fugitives were so completely beside themselves with fear that they ran past the Chancellor House, down the Fredericksburg pike, through Hancock’s line, and into the hands of the Confederates.”[3] Walker, though, had been wounded before Jackson’s attack.

Walker’s postwar history of the II Corps quotes someone referred to as General Morgan: “As the crowd of fugitives swept by the Chancellor House, the greatest efforts were made to check them. but those only stopped who were knocked down by the swords of staff officers or the sponge-staffs of Kirby’s battery, which was drawn up across the road leading to the ford. Many of them ran right on down the turnpike toward Fredericksburg, through our line of battle and picket line, and into the enemy’s line! The only reply … was, ‘All ist veloren; vere ist der pontoon [All is lost; where is the pontoon]?'”[4]

Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Morgan was the II Corps’ artillery chief at Chancellorsville, and, by the time Walker wrote his history, he achieved the rank of brigadier general.[5] Since the II Corps operated on the turnpike farthest from Jackson’s impact, and Hancock’s division straddled it, Morgan or Hancock either saw what happened or heard it from Kirby’s artillerists or the pickets. Although, if Kirby was on the road to the ford, who actually saw the flight down the turnpike? Morgan’s testimony, if not eyewitness, is pretty close.

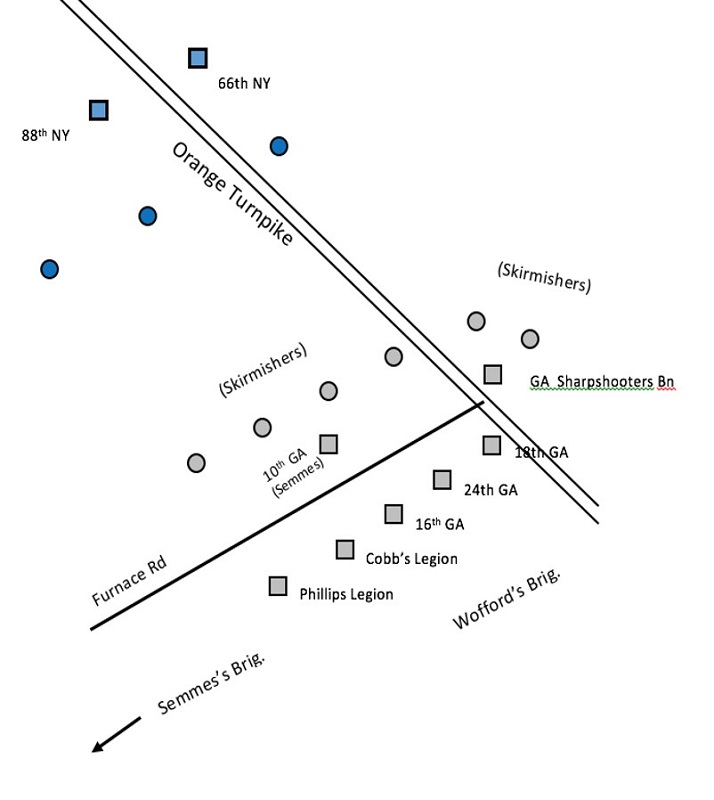

So, we’d like to hear from the pickets themselves, or even the “enemy” captors—from a line officer or regimental historian. True, it’s hard to know who was where for picket duty. During active fighting skirmishers were supplied by various regiments. It seems Union soldiers nearest the turnpike were from the 66th and 88th New York Infantry. The closest Confederates seem to have been from the 10th Georgia Infantry of Semmes’s Brigade. Anyone “flying” past them would have been scooped up by the right end of Wofford’s Brigade: the 18th Georgia south of the turnpike or the Georgia Sharpshooters Battalion north of it.

I’ve found no reports from the above units about XI Corps fugitives. One 18th Georgia historian states Wofford “cut off a large number of Union soldiers. They surrendered to the Confederates, and General McLaws would later credit General Wofford’s brigade with the ‘most credit for their capture,’ although the Tenth Georgia, General Semmes, and General Wright … claimed their share equally.”[6]

Indeed, the 10th Georgia’s colonel claimed a share: 340 soldiers from the 27th Connecticut, which had been trying to change position, found itself cut off, and surrendered. But the 27th was from the II Corps and was hardly fleeing.[7] We do have to wonder what it was doing where it was captured.

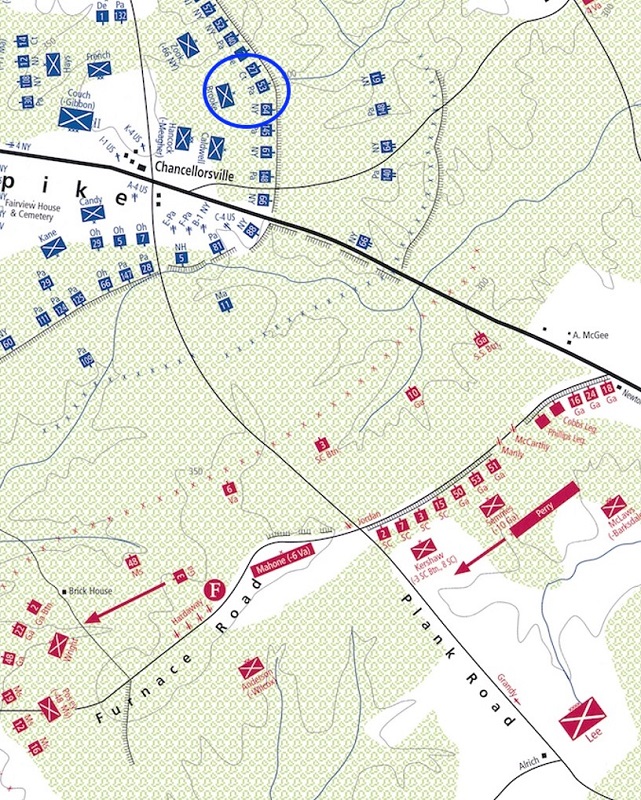

One report mentioning XI Corps captives comes from Gen. William Mahone, whose Confederate brigade was posted near the southern end of the line that evening, along the Plank Road. Mahone credits 6th Georgia skirmishers with the capture, “a little after dark,” of “prisoners from four different regiments, and the colors and color-bearer of the One hundred and seventh Ohio” when they “charged the enemy’s abatis near the Plank Road and fired upon him in his rifle pits.”[8]

The 107th Ohio was an XI Corps regiment, but was it fleeing? Its color-bearer seems to have been captured while defending a line of rifle pits. And, again, it was nowhere near the turnpike.

One who, after the battle, did investigate XI Corps’ performance was Augustus Hamlin of Maine. Hamlin was the Army of the Potomac’s medical inspector and later XI Corps historian. Though not attached to the corps at Chancellorsville, Hamlin served as its medical director the previous year and observed much anti-immigrant bigotry. He may also have had a further motive to clear his own name of an accusation of cowardice at First Manassas.[9]

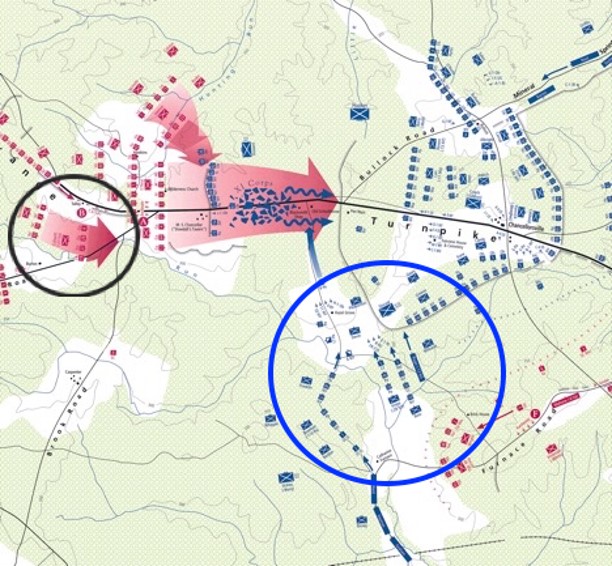

Hamlin’s 1896 study benefited from early editions of the Official Records, plus other letters and memoirs, and early enough that many veterans were still alive. Amassing evidence from both armies, Hamlin made a compelling case that any fugitives captured by the Confederates on the south end of the line were likely from the III and XII Corps withdrawing from an advance ordered earlier on May 2 by III Corps commander Dan Sickles into the wilderness around Catharine Furnace. Sickles’s goal was to disrupt Lee’s “retreat”—of which the Union command had decided Jackson’s flanking column must be a part.[10]

Hamlin considered Sickles’s adventure a fiasco that nearly cost the destruction of two divisions if not for Alfred Colquitt, a Confederate brigadier on the southern end of Jackson’s advance, whose failure to keep pressing ahead as ordered left an escape route open for at least one of the routed XI Corps divisions and one or more of Sickles’s. Even so, the withdrawal of troops from the furnace area was so tangled by the wilderness that two brigades of Williams’s XII Corps division spent some time firing at each other while trying to avoid being cut off. Some likely were cut off by the Anderson’s and McLaws’s Confederate divisions, as reported by the 18th Georgia historian. Hamlin showed this rout came largely from the III and XII Corps, and that any XI Corps fugitives had already been halted at the Chancellorsville clearing. [11]

The black circle shows the brigades of Colquitt and of Ramseur (who could not advance once Colquitt stopped), both well behind Jackson’s northern pincer. Hamlin is convinced that the Union rout from the Hazel Grove clearing (blue circle), where many ammunition and supply wagons were parked, and up a ravine to its east had a wide enough passage—absent interference from Colquitt and Ramseur— for Williams’ division and one of Sickles’s to escape.[12] And no one from the XI Corps was anywhere near.

If Morgan is credible, at least some Union soldiers were captured by the Confederates after blowing by their own skirmishers. Maybe some were “Dutchmen.” But there were plenty of other fugitives that night. Most of Brig. Gen. Devens’s XI Corps division, who stacked arms and were cooking supper—as ordered—had little choice but to run or surrender, but Hamlin shows the rest of the corps, including many Germans, fought hard until flanked. Hamlin blames leaders like Devens, who ignored warnings, as did XI Corps commander Oliver O. Howard, who, told to send his one reserve brigade to aid Sickles, went along himself and was just returning to his headquarters when the rout approached, having done nothing prepare his corps. Then there was army commander, Joseph Hooker, blinded by his own conceit that he outmaneuvered the great Lee.

Clearly much flying and floundering went on at Chancellorsville on the evening of May 2, and it seems clear that some of the disoriented Union troops captured on the McLaws-Anderson end of the line were from units besides the XI Corps, and at least some of the captives that were from that corps were not fleeing. Indeed, if we are to believe Hamlin and others, the corps was being reformed in the Chancellorsville clearing and along the route to U.S. Ford. Something like what Morgan heard from Kirby’s battery probably did happen, although, from that battery’s position, most of those fugitives likely fled up the ford road. It’s also hard not to agree with Hamlin that most of those captured by Anderson’s and McLaws’s brigades were from other corps. It’s also hard not to admire the bravery of those who did their duty—including most, it seems, of the poor XI Corps, to whom it has often been said that nothing good ever happened.

So, as with many wartime anecdotes, it seems a grain or two of likely truth was spun up into a vivid tale infused with ethnic stereotypes—no doubt a convenient one for those looking to excuse their own behavior.

Dan Walker has been an educator for more than fifty years, teaching English, creative writing, and interdisciplinary humanities in high school, and professional education at the undergraduate and graduate levels, first at the University of Mary Washington, then in the Virginia Community College System’s career-switcher program. He has a B.A. in History (1969) from William and Mary, an M.A. in English from U. Va., and an Ed. D. in English Education, Educational Supervision, and Research. He worked as a seasonal NPS Ranger for several years. Dan has published prizewinning poetry and short fiction, plus one book and several articles in professional education. He has also published three novels.

Endnotes:

[1] Stephen W. Sears, Chancellorsville. (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1996), 433.

[2] Henry N. Black (1865). Three Years in the Army of the Potomac (Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1865),179.

[3] Francis A. Walker, General Hancock (New York: Appleton, 1894), 83.

[4] Ibid, 228.

[5] Warner, Ezra J. Warner, “Charles Hale Morgan,” Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1964), 331-332.

[6] Randy Strickland, “The Battle of Chancellorsville and the 18th Georgia Regiment of Volunteer Infantry” https://www.angelfire.com/va3/southernrites/chancellor.html

[7] Report of Lieut. Col. Willis G. Holt, The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 25, Part 1, 838.

[8] Report of Brig. Gen William Mahone, Ibid, 863.

[9] “Augustus Choate Hamlin (1829-1905).” (2024) University Archives. University Companies Inc. https://www.universityarchives.com/auction-lot/map-of-chancellorsville-and-jackson-s-attack-prov_90D4D998BC.

[10] Augustus C. Hamlin, The Battle of Chancellorsville (Bangor ME, 1896).

[11] Ibid, 100.

[12] Hamlin, 124.

Great article thank you.

Good to read. Of course there was more than a “wartime anecdote” at work here. On May 5, 1863 there was a front page article in the New York Times which distorted the record and helped create the broad view among the public that the battle would have been a victory except for the “flight” of the Germans.

Thank you for a great article and even greater research. I have focused on May 2, 1863 for most of my studies. I do not think that Chancellorsville was Lee’s “Greatest Battle” but rather his “Last Hurrah” and was fabricated to hide an extremely flawed operation, that smacks of dereliction of duty with his two top field commanders being wounded because they were in a foolish attempt to save a wasted day. Your article helps me confirm some of my doubts about Jackson and Lee. Colquitt was responsible for 40% of the ANV line being absent at the front.