The Civil War General Who Helped Transform One of the World’s Best Fire Departments

Colonel George Spear, commanding a pivotal assault column tasked with driving Confederates from the daunting Marye’s Heights, dropped dead in the road. His soldiers, caught in the open roadway and now leaderless, stalled. It was May 3, 1863, and the Second Battle of Fredericksburg had the beginnings of the same disaster as its predecessor five months earlier.

“The head of the regiment was literally blown back, telescoped on itself,” a Federal soldier noted, “both from artillery in our direct front and flank, and the more destructive infantry practice.”[1] Others dived for cover in ditches and more men died as the artillery fire showed no signs of slacking. Federals started to fall back in chaos, running for safety.

And then Colonel Alexander Shaler arrived. Shaler, 36-years old and with a large drooping moustache, commanded a brigade behind Spear’s column. Seeing the devastation, and realizing the moment hung in the balance, Shaler rode up to rally the troops. “It is not your fault,” he told the soldiers in the road, “go back, every man for himself, and take the battery.”[2] With Shaler at the head of the column, the soldiers redoubled their efforts, charging through the fire and up the heights. They swarmed the Confederate positions, nabbing guns and prisoners alike. A witness wrote to Shaler’s wife: “He was the only mounted officer who ascended the heights, and although in the outset the leading regiment broke and fell back, causing much commotion. . . at this critical moment the colonel dashed forward, seized the flag, and shouted with a loud voice—‘Come on, boys!’ they did ‘come on’ with a yell. Another moment and our brave colonel stood upon the ramparts waving the dear old flag high in the air.” Shaler’s leadership at Second Fredericksburg earned him a brigadier general’s star, and thirty years later he received the Medal of Honor for his spur of the moment command decisions.[3] That same type of leadership would prove invaluable after the war, with a different kind of fighting.

He was born in Connecticut but spent most of his life in New York City. In the 1840s, he joined a militia company, and by 1861 published a light infantry tactics manual. With sectional divide and the outbreak of war, Shaler received a commission in the 65th New York Infantry, also known as the 1st U. S. Chasseurs. He served in nearly every major battle from the Peninsula onwards—a biographical sketch written of Shaler in 1867 said “To follow Colonel Shaler through all the battles in which he was engaged, is almost to write the history of the war in Virginia.”[4] Shaler became a prisoner of war at the battle of the Wilderness and spent time in a Confederate prison before being exchanged in August 1864. He ended the war commanding a division in Arkansas and mustered out of Federal service in August 1865.[5]

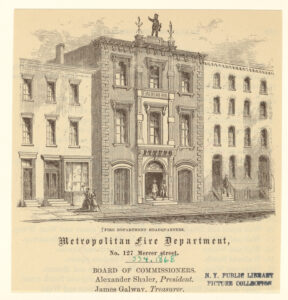

The cessation of hostilities brought Shaler back home to New York City. In January 1867 he received a commission as a major general in the New York National Guard. Four months later, Shaler received an appointment as president of the five-man commission heading the Metropolitan Fire Department of New York City.

Firefighting in New York had been, since the city’s establishment in the 17th century, a volunteer endeavor. The volunteers came from a variety of backgrounds—ranging from the rough and rowdy street gangs to skilled laborers who fought fires as the need arose. They were tough as nails, and famous for being able to brawl competing fire companies with as much vigor as the flames.[6]

With the outbreak of war, firefighters joined the ranks of nearly every New York regiment, and their feats became legendary on the battlefield (the 73rd New York even chose to depict a firefighter standing next to a soldier on their monument at Gettysburg), though the actions and misbehaviors of some fire companies during the worst of the Draft Riots in 1863 were a stain on their collective record.[7]

Even before the war ended, city officials were pushing to phase out the city’s volunteers with a concentrated and organized paid department. Though many volunteers resisted, the tides of change were unrelenting, and the Metropolitan Fire Department was officially created in August 1865. Thus, this paid department was less than two years old when Alexander Shaler became the president of the commission in 1867.

Shaler immediately brought his military experience to the department. He reorganized the entire command structure, instituting a series of ranks that fire departments across the country soon adopted, and continue to use to this day. Officers who had before gone by such titles as “Assistant Foreman” and “Foreman” now became lieutenants and captains, respectively. Fire companies were organized into battalions, and battalions were grouped into divisions. Shaler personally “organized and taught classes composed of the officers and engineers in their respective duties.” He created grooming standards, for both the firefighters and their living quarters, and demanded that prospective firefighters “pass a rigid physical examination.”[8] Shaler and his co-commissioners’ trainings paid off: “Each company was placed on a basis of efficiency equal to that of a regular section of field artillery. Each man had his place and duty, which he was expected to perform.”[9]

The differences soon became apparent to the public. Within just a year and a half of taking the reins, Shaler’s leadership was noted by a newspaper correspondent who wrote, “The well-disciplined and soldiery mind of the President of the Commissioners, General Alexander Shaler, has evidently impressed itself most effectually upon the entire force, and the consequence is that a thorough system of disciple exists which renders the paid department infinitely more effective than the old volunteer system.”[10]

The year 1870 proved to be among the busiest of Shaler’s time as commissioner. Through the political machinations of William “Boss” Tweed, an act passed into New York law, wresting control of the fire department away from the state, and putting it into the city’s hands. It was a naked power grab by Tweed, that put more money into his pocket, but also led to a rebranding of the department. With Shaler still at the helm as commissioner, the Metropolitan Fire Department was replaced by the Fire Department of the City of New York. The name was frequently abbreviated, and the lettering began to soon appear on all the fire engines and ladder trucks in the city: FDNY.[11] That same year Shaler oversaw installation of nearly 350 telegraphic alarm boxes throughout the city—which sped up response times and gave firefighters more accurate information about the locality of emergencies.[12] In large part due to these changes and policies, damage from fire losses in 1870 amounted to $2.1 million, down from $6.4 million in 1866—a nearly 68% difference.[13]

Shaler’s term as commissioner ended in April 1873. But his service with fire departments was not finished. A year later and reeling from their second great fire in three years, Chicago officials invited Shaler to visit and provide recommendations to better their own department.[14]

His policies and reforms spread across the nation, and the foundations of many modern fire departments remain the core essence of what Shaler sought to accomplish. The New York City Fire Department is one of the most respected and famous firefighting organizations in the world, responding to nearly two million calls for assistance a year. But whether it be in major cities like New York or Chicago, or innumerable smaller rural towns throughout the United States, the populace lives safer and better lives because of Alexander Shaler.

[1] Robert L. Orr, “Marye’s Heights: The Bloody and Desperate Assault by the Sixth Corps,” Philadelphia Weekly Press, Jan. 19, 1887.

[2] A.T. Brewer, History of the Sixty-First Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-1865 (Pittsburgh: Art Engraving & Printing Co., 1911), 54.

[3] Unknown Author, “Major General Alexander Shaler,” The Northern Monthly: A Magazine of General Literature (Newark: New Jersey State Literary Union, 1867), 18.

[4] Ibid., 16.

[5] Ezra Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964), 434-35.

[6] Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 5, 293-4, n.5; Terry Golway, So Others Might Live: A History of New York’s Bravest, The FDNY From 1700 to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 69.

[7] See Bernstein, 18-19, 21-22.

[8] Golway, 129; Augustine Costello, Our Firemen: A History of the New York Fire Departments (New York, Self Published, 1887), 838-39.

[9] Costello, 840.

[10] New York Daily Herald, Nov. 15, 1868, Page 6.

[11] Golway, 130; Costello, 853.

[12] Fire Department of the City of New York: 1910 Annual Report (New York: Lecouver Press Company, 1911), 131.

[13] Costello, 838.

[14] Chicago Tribune, Oct. 18, 1874, Page 4.

Wow — thanks for this terrific story … i always wondered why firefighters were organized in companies, battalions, and divisions with captains and lieutenants … now i know … and the analogy to an artillery battery makes sense as well with each firefighter assigned a specific task … BG Shaler even looks like a fireman!

Thanks! And he certainly does have the right moustache for it, doesn’t he.

This is a great post on a subject I knew nothing about. Thanks.

Thanks for reading!

Superb article on a little known impact of the Civil War!

Thank you!

I always wondered why fire departments had military ranks… now I get it! Great post on an unsung hero, on and off the battlefield!

Thanks for reading, and the comment!

Great post. Really enjoyed learning about Shaler and his impact not only in the Civil War but as a director of FDNY.

Thanks for reading!

Great post! Thanks Ryan!