“The First Thing We Do, Let’s Kill All the Lawyers”: Henry Halleck, Esq.’s Parole Order Fiasco

ECW welcomes back guest author Kevin C. Donovan.

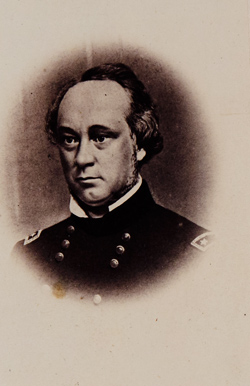

Abraham Lincoln disparaged General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck as “little more than a first-rate clerk,” while Navy Secretary Gideon Welles called him “good for nothing.”[1] They were too kind. Halleck was not simply useless; he was single-handedly responsible for one of the most inane orders issued during the Civil War, which arose from Halleck playing lawyer.

Pre-war, Halleck was a successful lawyer.[2] His interest in things legal persisted during the war. In December 1862, Halleck tasked a committee to draft a “code of regulations for the government of armies in the field, as authorized by the laws and usages of war.”[3]

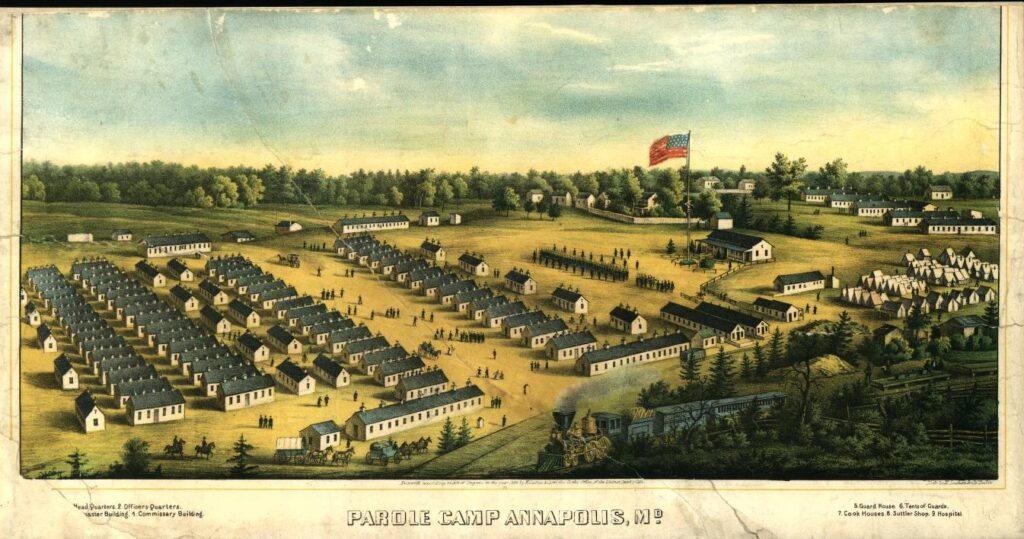

One subject Halleck wanted addressed was paroles, the system of captured soldiers being released based on their promises not to fight until formally exchanged. Halleck objected to the Confederate practice of granting paroles on the battlefield, rather than taking custody of the prisoners and delivering them for exchange at a site designated by the Dix-Hill Cartel, the 1862 agreement governing POW issues.[4] In September 1862 alone, 11,000 Federals captured at Harpers Ferry and 4,000 taken at Richmond, Kentucky had been paroled on the battlefield. Apart from being freed from having to guard the POWs – A. P. Hill’s unencumbered men had promptly marched from the parole field to Sharpsburg just in time to help turn the tide of battle there – the Confederacy was relieved of the cost of housing and feeding thousands of men, while simultaneously taking them out of action until they were exchanged for Confederates.[5] Worse, “parole camps” established by the Uniteds States to prevent paroled soldiers from deserting soon became centers of crime and insubordination.[6] At the same time, multiple Union field commanders complained battlefield paroles violated the procedure established by the cartel. Halleck agreed the Confederate practice was unlawful according to the terms of the cartel and wanted to rein in paroles.[7]

Approved in late April 1863, the Lieber Code (named for its primary author, Francis Lieber) did crack down on paroles, announcing that captured soldiers must generally be taken into custody. Mass battlefield paroles were forbidden, and other parole restrictions were imposed. Paroles inconsistent with the new rules were deemed void.[8] Moreover, to discourage improper parole acceptance, Lieber – who felt that paroles placed “a premium on cowardice” – provided in Article 131 of his Code: “If the government does not approve of the parole, the paroled officer must return into captivity” [emphasis added].[9] Notably, Lieber’s “return into captivity” principle was not part of the Dix-Hill Cartel.

Halleck, meanwhile, had been so anxious to address the parole issue that he did not wait for the new code. Rather, the erstwhile lawyer took Lieber’s parole work in progress, reworked it, and on February 28, 1863 issued General Orders No. 49, setting forth the Union’s new military law of paroles.[10] As shown below, Halleck’s Order No. 49 must be considered among the most ill-advised – if not outright nonsensical – orders issued during the Civil War.

Lieber’s suggestion that individual officers would be forced back into captivity seemed absurd, but the threat might serve as a deterrent. The problem was created, however, when Halleck decided not only to adopt Lieber’s “return into captivity” principle, but expand it to encompass all paroles.[11] Halleck’s Order No. 49 committed Lincoln’s government to force all improperly paroled soldiers back into Confederate captivity, even those who had simply followed their commander’s decision to surrender and accept parole. Moreover, Halleck mandated that his order “be officially communicated by every General commanding an army in the field to the Commanding General of the opposing forces.”[12]

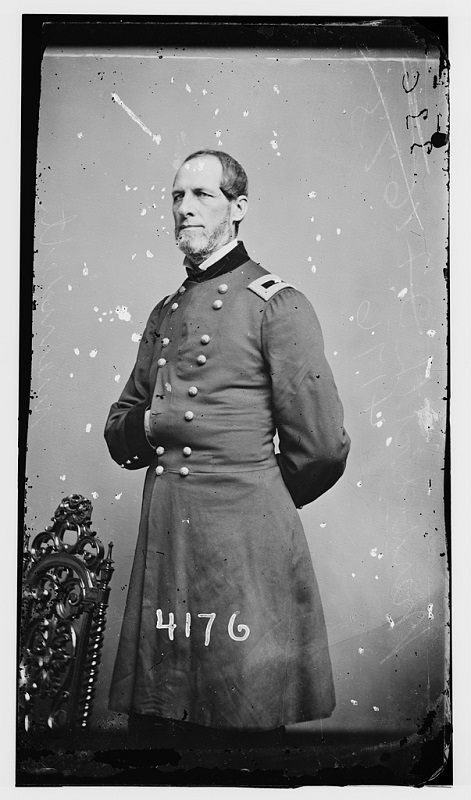

The outcome was predictable and embarrassing. Rebel commanders blithely continued mass battlefield paroles. Then the Confederates insisted that if the U.S. chose not to honor the paroles given by thousands of Union prisoners taken during the Gettysburg Campaign, the federal government’s own rule obligated it to return those Union soldiers to captivity in the South.[13] As Confederate Agent of Exchange Robert Ould asserted to his U.S. counterpart – Solomon A. Meredith – on August 5, 1863, simple justice required the federals to obey its own announced policy: “Before the 3d of July, 1863, a large number of your officers and men were captured and paroled by our forces in Maryland and elsewhere … I shall insist that these paroles shall be respected and equivalents given for the officers and men named therein, or that the parties giving them shall be delivered in person at City Point. In doing so I only carry out your own general order in force at the time.”[14]

Obviously, the Lincoln Administration was not about to force thousands of Union soldiers back into Southern captivity. Nor was it inclined to accept Ould’s alternative suggestion and release thousands of rebel POWs to match the number of U.S. soldiers whose paroles it deemed void.

Halleck’s folly had already been recognized. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton belatedly corrected Halleck’s blunder. Stanton’s July 3 Order No. 207 announced that paroles inconsistent with the Dix-Hill Cartel simply would not be honored.[15]

But the damage had been done. Ould quite naturally refused to let Halleck off the hook, repeatedly insisting that Halleck’s prior order be honored during the period it was in effect.[16] This placed the U.S. in a quandary; either honor Halleck’s order or repudiate the policy established by its top general (in his self-appointed role of military lawyer).

Over the course of several months, federal officials tried a variety of approaches to twist out of the dilemma created by Halleck. Feigning ignorance of his own order, Halleck blustered that Ould’s return-to-captivity position was “a most extraordinary demand.”[17] In October, Meredith advised Ould that in issuing Order No. 49, the U.S. had only been warning that henceforth the cartel provisions would be strictly enforced. Meredith too simply ignored Halleck’s “return to captivity” policy.[18]

Ould was not having this. He continued to hammer his federal counterpart with Halleck’s “return to captivity” principle which, Ould wryly noted, “was advertised to us as being the controlling law of the case.”[19]

The U.S. arguments continued to evolve. In November Ould was told that Halleck’s order was simply an internal U.S. Army disciplinary device. The same missive described the cartel as the “highest authority” on paroles, “analogous to a treaty.”[20] A careful observer could sense what final humiliating position the federals were reluctantly approaching.

That came on November 7, 1863, when Meredith finally gave up trying to defend the indefensible. Instead, Meredith advised that it was the U.S. position that Halleck’s Order No. 49 violated the terms of the cartel and thus was unlawful and void from the start.[21]

Apart from the embarrassment, Halleck’s unfortunate decision to play military lawyer had other consequences. The dispute he created led to certain unilateral Confederate actions releasing its troops from parole. This resulted in cries of bad faith. Insults flew between Meredith and Ould. Their relationship became so poisonous that it hampered prisoner exchange cooperation, and Meredith ultimately was removed.[22]

“The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.”[23] That verdict might seem a bit harsh even against Halleck. However, if his foolish military law malpractice played even a small role in extending the stay of a Union POW in Libby Prison or Andersonville, that soldier might agree with Shakespeare’s statement at face-value.

Kevin C. Donovan, Esq., a retired lawyer, now focuses on Civil War research and writing, including on law-related topics such as “How the Civil War Continues to Affect the Law,” published in Litigation, The Journal of the Section of Litigation, of the American Bar Association. His inaugural ECW blog publication, “A Tale of Two Tombstones,” appeared December 9, 2022 and was ECW’s most popular post of the year on social media.

Endnotes:

[1] James M. McPherson, Tried By War: Abraham Lincoln As Commander In Chief (New York, The Penguin Press, 2008), 119; Edgar T. Welles, Ed., The Diary of Gideon Welles, (Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1911), Vol. 1, 384.

[2] Stephen E. Ambrose, Halleck: Lincoln’s Chief of Staff (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 8.

[3] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of The Official Records of The Union and Confederate Armies, Series III, Vol. 2, 951 (hereafter OR); John Fabian Witt, Lincoln’s Code (New York: Free Press, 2012), 229.

[4] OR, Series II, Vol. 4, 266-268.

[5] Hill had not the men to guard 11,000 prisoners and his forced march managed to bring only about 2,000 men to the Sharpsburg fight. James M. McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 114, 128; Bert Dunkerly, “Antietam’s Lower Field Revisited Part IV: A.P. Hill’s Not-So-Devastating Counterattack,” Emerging Civil War, June 17, 2021.

[6] Roger Pickenpaugh, “Prisoner Exchange and Parole,” Essential Civil War Curriculum.

[7] OR, Series II, Vol. 5, 70, 191-192, 198, 237, 237-238, 256, 301-302 ; Matthew J. Mancini, “Francis Lieber, Slavery, and the ‘Genesis’ of the Laws of War,” The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 77, No. 2 (May 2011), 330, 339-341; Witt, 230, 254-255; Ambrose, 130.

[8] OR, Series III, Vol. 3, 148-164.

[9] Mancini, 339.

[10] OR, Series II, Vol. 5, 306-307; Ambrose, 130; Mancini, 340-341.

[11] OR, Series II, Vol. 5, 306-307 (Section 8).

[12] OR, Series I, Vol. 25, part 2, 145-146; OR Series II, Vol. 5, 925; Albert Z. Conner Jr. & Chris Mackowski, Seizing Destiny: The Army of the Potomac’s “Valley Forge” and the Civil War Winter that Saved the Union (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2016), 188-189.

[13] Witt, 255-256.

[14] OR, Series II, Vol. 6, 179-180 (emphasis added); Almost 4,000 Union prisoners had been taken in the June 13-15 Second Battle of Winchester alone. Edwin B. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1984), 89, 225-226.

[15] OR, Series II, Vol. 6, 78-79; Witt, 255-256.

[16] OR, Series II, Vol. 6, 225-226; Robert Ould, “The Exchange of Prisoners,” Alexander Kelly McClure, Ed., The Annals of the Civil War Written by Leading Participants North and South (Philadelphia, 1878), 32, 34, 35, 40.

[17] OR, Series II, Vol. 6, 199.

[18] Ibid, 388-389.

[19] Ibid, 339, 346, 550 (emphasis added).

[20] Ibid, 472.

[21] Ibid, 481-482.

[22] Ibid, 303, 316, 332-335, 341, 441, 452-455, 533, 553, 1010.

[23] Henry VI, Part 2, Act IV, Scene 2.

I’m more a Halleck fan than you, Kevin, but “kill all the lawyers” sounds like something Halleck WOULD say rather than the Bard!

Peter, I actually am open to being educated on Halleck’s virtues (any suggestions on what to read?), but as a “recovering” (i.e., retired) lawyer myself, I just cannot get past the extremely poor drafting of his order, particularly the blatant ignorance of its practical consequences. Back when I was in practice (when Patrick Henry & Thomas Jefferson roamed the Earth), a goal of drafting policies was not just to comply with applicable law, but to implement the client’s goals in a reasonable fashion. How Halleck came to think that his “return to captivity” order made any sense just escapes me. Now, there are issues that I did not have the space to address in the blog post. Thus, and interestingly, some time before Halleck’s order, Lincoln himself opined to Halleck that certain soldiers who had entered into improper paroles should be sent back to the Confederates. Also, Halleck’s order was issued only one day after he promised General Rosecrans that he (Halleck) would address Rosecrans’ request to deem invalid any paroles that did not comply with the provisions of the Dix-Hill Cartel. Maybe Halleck rushed through his paper, and improvidently relied upon what Frances Lieber then had in draft. But again, a lawyer must think through how his/her work will apply in the real world. Halleck failed that test. His order was – in legal terms – dumb. Thank you for reading.

Thanks for responding!

Halleck made mistakes but I don’t think he was totally incompetent. But everybody screws up once!

It’s fun to bash Henry Halleck: the adequate clerk with goggle eyes and itchy elbows. And it must be remembered that Halleck was Winfield Scott’s selection to assume Army Command middle of 1861; but Halleck’s tardy arrival from California resulted in Lincoln’s “Captain’s pick” of McClellan to fill that role. And Halleck was consigned to command of the Department of Missouri. While overseeing Curtis, Foote, Pope, Grant and finally Buell, Halleck helped orchestrate and provided crucial logistical support for Union victories at Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, Pea Ridge Arkansas, New Madrid and Island No.10 …and the near-bloodless occupation of impregnable Fort Columbus Kentucky and strategic Corinth Mississippi, crossroads of the two most important Confederate railroads in the West. And when McClellan faltered in front of Richmond in July 1862, Halleck was called east.

There is more than enough collective blame for the abusive POW systems operated during the Civil War, North and South: Winder, Wirz and Sanger; half-rations; dead lines… and the Parole Camp was Edwin Stanton’s idea. Halleck did nothing to improve upon the odious POW system he inherited… a system that remained “an American Tragedy” through the end of the war.

thanks Kevin, great piece … sometimes the “smartest” officers issue the dumbest orders … sounds as if Grant (or his staff) either didn’t read the order or just ignored it as they paroled Pembertons entire army after Vicksburg … like your reader above, i have softened my opinion of “Old Brains” … he was an awful general in chief for Lincoln, but pretty good chief of staff for Grant — part of the team that won the war.

Mark, thank you. I need to learn more about Halleck overall to be sure.

As for Grant’s paroles, you raise a good point with an interesting answer. Grant actually tried to comply with the Dix-Hill Cartel and avoid the charge that he copied the “battlefield parole” practice of the Confederates. The Cartel named two sites for the formal physical delivery of POWs. One of those was Vicksburg itself. And Vicksburg had a CSA officer of exchange assigned to the post. So Grant cleverly refused to take that exchange officer prisoner. Then, he turned over the names of all the Vicksburg parolees to him. Thus, Grant complied with the letter of the Cartel.