Tales from a Monk in the Union Army: The Shenandoah Valley Campaign

By the summer of 1864, the war showed no signs of ending for Br. Bonaventure Gaul.

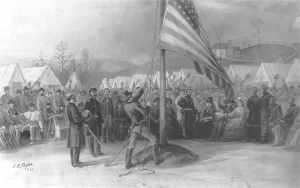

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant and the Union Army of the Potomac remained gridlocked in the Siege of Petersburg, while Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s armies stalled outside of Atlanta. To draw Confederate attention away from Petersburg and wreak havoc upon the Confederate war effort, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan led a detachment of the Union army consisting of the Sixth Corps to retake the Shenandoah Valley. Gaul, a Catholic Benedictine monk in the 61st Pennsylvania, marched into the Valley that summer with Sheridan.[1]

For nearly three months, Sheridan’s army waged total war up the Shenandoah Valley, burning crops and destroying anything of value to the Confederate war effort. As the 61st fought in the battles of Third Winchester and Fisher’s Hill, Gaul tended to the regiment’s sick and wounded as a hospital orderly. “The wounded lay around on the bare ground during the night without blankets (at the beginning there were none available),” he recorded, “[and] the worms [grow] by heaps.”[2]

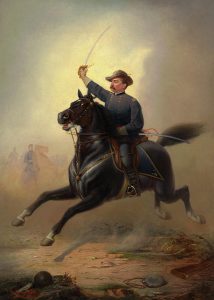

On October 19, 1864, Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s Confederate force ambushed Sheridan’s army encamped along Cedar Creek near Middletown, Virginia. Early succeeded in driving three Union corps from their positions, but Sheridan’s arrival from Winchester in the afternoon turned the tide of battle. He rallied the Union army in a counterattack that crushed the Confederate offensive.[3]

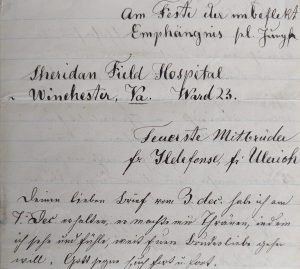

Gaul did not witness the fighting firsthand, but he watched as casualties trickled into the Sheridan field hospital in Winchester. On October 24, exactly 160 years ago today, he wrote his friend and fellow monk Brother Ildephonse Hoffmann about the horrific sights of the hospital. “I have experienced more than 30 battles; but this one seized me for sheer sympathy.”[4]

For nearly a month, Gaul and the other orderlies tended to both Union and Confederate soldiers in the field hospital. “Day and night for 30 days there was no rest. Ach, how many died in my arms!” he lamented. Then he described how the VI Corps triumphantly repulsed the rebels while the VIII Corps “ran like dutchman.” “If General Sheridan had not come at the right time,” Gaul professed, “we would have been beaten back 30 miles.”[5] Gaul took great pride in the VI Corps’ role in winning the battle of Cedar Creek. “Our corps certainly deserves the honor,” he boasted to his friend, writing that they “fought with the rage of lions.”[6]

But even in light of a Union victory at Cedar Creek, Gaul took note of the Valley campaign’s cost. “Our brigadier general, the fat old gray man, whom you surely remember, was killed by a bomb shell,” he wrote to Br. Hoffmann. That general was Daniel D. Bidwell, commander of the 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, VI Corps. Bidwell led his brigade in a rearguard action against the Confederates when he was struck by a shell and felled from his horse.[7]

Likewise, Gaul’s friend and fellow draftee Pvt. George Kunstler suffered a wound through the chest. “He suffered quietly and meekly,” the young monk wrote, “[but] I bandaged him and cared for him.” Kunstler transferred to the north hospital on October 20 for further recuperation. Captain Lewis Redenback of Gaul’s Company B died of his wounds from the battle of Summit Point in August 1864, while one of Gaul’s comrades who he refers to only as “Old Thomas” succumbed to his illness in Baltimore on September 6. “Our regiment is very small,” Gaul mused. He noted that more draftees had arrived to replace the old veterans, but not enough to replenish the men lost throughout the Valley.[8]

Gaul remained at the Sheridan field hospital until January 1865, almost a month after the VI Corps marched out of the Valley to rejoin the Siege of Petersburg. He shivered through the frigid winter and frequently fell ill. “I had no stove, no blanket, no coat to protect me from the cold [during my] work in the hospital,” he recalled. Gaul persistently called upon his abbot and other Catholic allies to release him from service. But the recent Union victories made him realize he would likely see the war through to its end—whenever that may be.

[1] Scott C. Patcham, Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 41; Bonaventure Gaul to Ulrich Barth, November 21, 1864, translated by Fr. Warren D. Murrman, O.S.B., VH-41, “Letters of Civil War,” Archives of St. Vincent Archabbey, Latrobe, PA.

[2] Bonaventure Gaul to Ildephonse Hoffmann, October 24, 1864, translated by Fr. Warren D. Murrman, O.S.B., VH-41, “Letters of Civil War,” ASVA; Jonathan A. Noyalas, The Battle of Cedar Creek: Victory from the Jaws of Defeat, (Charleston: The History Press, 2009), 18-19.

[3] Noyalas, The Battle of Cedar Creek, 11-12.

[4] Gaul to Hoffmann, October 24, 1864, ASVA.

[5] Gaul to Hoffmann, October 24, 1864, ASVA.

[6] Gaul to Hoffmann, October 24, 1864, ASVA.

[7] Jack H. Lepa, The Shenandoah Valley Campaign in 1864, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2003), 195; Gaul to Hoffmann, October 24, 1864, ASVA.

[8] Samuel Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5: Vol. II (Harrisburg: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869), 414; Gaul to Hoffmann, October 24, 1864, ASVA.

Yep, in 1863, Union soldiers burned the crops, the stored hay and oats, and the barn of the Widower Riordan – who farmed a “spot of land.” The Riordan family, with 9 children, disappeared from the Shenandoah valley soon afterward.

Tom

For sure; thanks for sharing that anecdote.

Thanks, Evan, I recall your informative piece on the monks of St Vincent and their required service.

Thank you! Part 3 is in the making, as well!