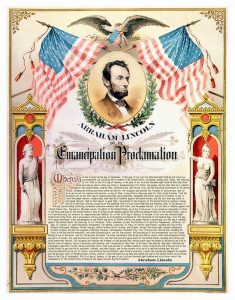

Lincoln’s “Second Thoughts” on the Emancipation Proclamation

Presidential executive orders have been in the news of late. But the most famous executive order was signed 162 years ago.

“I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper. If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.” So spoke Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863 in putting his signature to the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln had paused to allow feeling to creep back into his arm, “stiff and numb” from shaking hands for three hours at a New Year’s reception. He did not want to produce a shaky signature, lest anyone than think that he was having second thoughts about his action.[1]

Actually, Lincoln had experienced second thoughts since issuing his “Preliminary” Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862.[2] That pronouncement had warned the insurrectionist states that unless they returned to the Union, Lincoln would declare their enslaved people “forever free.” Of course, Lincoln did issue his final proclamation. Yet in the intervening 100 days his mindset with respect to this sensitive political and moral subject clearly evolved and, in some measure, changed significantly from his approach set forth in the Preliminary Proclamation. Indeed, that initial Lincoln statement is so different from his final proclamation[3] that the changes warrant scrutiny. Such an examination illuminates Lincoln’s shifting thought on critical issues surrounding emancipation. Moreover, the review shows Lincoln’s wisdom in giving the matter second thought, because his Preliminary Proclamation was a highly flawed document.

The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

Ironically, the first thing that leaps out from the Preliminary Proclamation is that the Lincoln of September 1862 wanted to assure the public that the war was not being fought to free the enslaved. In the first sentence of his Preliminary Proclamation Lincoln reiterated that “I … do hereby proclaim and declare that hereafter, as heretofore, the war will be prosecuted for the object of practically restoring the constitutional relation between the United States, and each of the States….” The man who would become known as the “Great Emancipator” was preemptively refusing that title by stressing that the purpose of the war would continue to be restoration of the Union, only.

Next, Lincoln announced that he intended again to urge Congress to adopt a plan of compensated emancipation. In the same paragraph, the president assured whites who might be uncomfortable with the prospect of large numbers of freed blacks among them that “the effort to colonize persons of African descent, with their consent, upon this continent or elsewhere…will continue.” Lincoln knew that he was skating on political thin ice.

What followed was the heart of his preliminary announcement—a future targeted freeing of certain enslaved. Specifically, those enslaved persons within “any State, or designated part of a State,” that as of January 1, 1863 was then still in a state of rebellion “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”[4] Lincoln added that the military was to “recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.” (Lincoln would have second thoughts about that last phrase in particular.)

Lincoln then shifted gears, and for no apparent reason called “attention” to two laws. First highlighted was an act that prohibited the military from returning fugitive slaves to their owners.[5] The second was a July 17, 1862 act (the Second Confiscation Act). Lincoln quoted a portion of that law that deemed free those enslaved persons, held by persons engaged in rebellion, who escaped into Union lines. He then quoted another provision providing that any enslaved person who escaped from any state or territory into another state, was not to be “impeded or hindered of his liberty,” unless the fugitive’s owner swore that he had not supported the rebellion. Perhaps this last reference represented Lincoln’s effort to reassure loyal slave states that Lincoln was not targeting them. But the provisions quoted by Lincoln failed to support, and arguably barred, Lincoln’s plan to free immediately by executive action all enslaved persons currently within the geographic limits of any state in rebellion, regardless of the loyalty of an affected citizen within that jurisdiction.

Moreover, Lincoln failed to call “attention” to the fact that the Second Confiscation Act—which of course he had signed into law—mandated that before any enslaved persons who had not escaped could be deemed free, court proceedings (due process) had to be instituted against the enslaved person’s owner and a conviction for treason or insurrection obtained.[6] Again, Lincoln’s intent, as expressed in his Preliminary Proclamation, was to bypass an act of Congress when he implemented his own emancipation program. Why he was essentially calling “attention” to the fact that his future action would be illegal Lincoln did not explain.

Lincoln did add that he would recommend compensation for loyal citizens who had lost enslaved persons by any acts of the United States. In other words, Lincoln’s Preliminary Proclamation called attention to a Congressional act binding him that Lincoln announced he planned to violate, but Lincoln would urge compensation for those harmed by his decision to ignore the law.

Notably, the Second Confiscation Act, in section 11, had tacitly authorized the President to employ African Americans as soldiers.[7] Lincoln made no reference to this provision. At this point he seemed to focus more on ridding the country of freedmen through colonization than allowing them to fight for their country.

In sum, although he had been thinking about and drafting his plan for months,[8] Lincoln’s Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was an inartful hodgepodge of conflicting messages and highly dubious legality. Indeed, Lincoln identified no legal authority or even a theory purporting to justify his threat to emancipate millions of enslaved persons. He did not, for example, claim that his action was justified as a necessary war measure under his Constitutional authority as Commander-in-Chief of the military. Curiously, in the draft he read to his Cabinet on July 22, Lincoln had deemed his decision “a fit and necessary military measure,” and referred to his authority as Commander-in-Chief. But that justification oddly disappeared from the final Preliminary Proclamation.

Thus, one would certainly hope that Lincoln would have second thoughts about his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation because it was, to use a technical legal term, a “hot mess.”[9]

The Final Emancipation Proclamation

The executive order Lincoln signed on January 1, 1863 bears scant resemblance to its preliminary predecessor. First, the Emancipation Proclamation is a tighter document.[10] It is clearer and better organized. It makes more sense. Finally, it fixes several problems extant in the earlier document.

The Proclamation opens by quoting Lincoln’s earlier warning that enslaved persons in areas still in rebellion would be declared free. Lincoln then identifies those areas, and declares that all enslaved persons therein “are and henceforward shall be free.…” There is no mention of colonization, or compensation to any putative owners. Those persons are free, period. Short, clear, and to the point.

Lincoln then gives an order to the newly-freed people: “And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense.…”[11] This provision corrected an unfortunate turn of phase in the Preliminary Proclamation, in which Lincoln had assured the enslaved population that the U.S. military would not intervene “in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.” This provision was perceived in many quarters, including abroad, as an invitation to the enslaved to rise up in a bloody servile insurrection.[12]

Further, Lincoln’s thinking had evolved on another key issue. In his new Proclamation, he invited African Americans to join the fight as soldiers and sailors. Colonization was out; United States Colored Troops were coming.

But the biggest improvement on the Preliminary Proclamation was the fact that Lincoln had reconsidered the issue of his legal authority to promulgate his new executive order. Gone was any reference to a law (Second Confiscation Act) that actually harmed his position. Gone too was any ambiguity over the theory that Lincoln now grasped as his weapon to defend and enforce his newly more radical edict. Lincoln announced clearly the source of his authority: “I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and Government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion…” was taking these actions.

In closing this much more effective document, Lincoln both reiterated the source of his legal authority and appended a moral justification to his action while simultaneously appealing to an even higher authority: “And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.”[13]

Since issuing his Preliminary Proclamation, Lincoln in fact had had “second thoughts” on emancipation. And those thoughts resulted in a better, stronger, and more just, final executive order—the Emancipation Proclamation.

[1] Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (Simon & Shuster, New York, NY, 2005), p. 499; John Hope Franklin, “The Emancipation Proclamation: An Act of Justice,” Prologue Magazine, National Archives and Records Administration, Summer 1993, Vol. 25, No. 2, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1993/summer/emancipation-proclamation.html#:~:text=In%20the%20Preliminary%20Proclamation%2C%20the,draft%20about%20the%20use%20of.

[2] “The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, 1862,” National Archives and Records Administration, https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals_iv/sections/preliminary_emancipation_proclamation.html#.

[3] “Abraham Lincoln, Proclamation 95—Regarding the Status of Slaves in States Engaged in Rebellion Against the United States [Emancipation Proclamation],” Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/203073.

[4] Lincoln—who had read his Preliminary Proclamation to his Cabinet—had accepted a recommendation from Secretary of State William Seward to remove language that seemed to limit the recognition of the freedom being declared to Lincoln’s term of office. Lincoln had told Seward that he was not certain he lawfully could promise permanent freedom but agreed to make the suggested change. Goodwin, p. 482.

[5] This law made no distinction between owners who were or were not supporting the rebellion. It simply took the military out of the business of returning escaped fugitives.

[6] John Syrett, The Civil War Confiscation Acts: Failing to Reconstruct the South (Fordham University Press, New York, NY, 2005), pp. 192-196 (text of the Second Confiscation Act and explanatory Joint Resolution).

The Second Confiscation Act also provided a separate type of proceeding (“proceedings in rem”) to govern the “condemnation and sale” by the government of property seized from persons aiding the rebellion; however, it did not appear that this method applied to enslaved persons. Syrett, p. 63. In any case, again there had to be an actual court proceeding employed; unilateral executive action was not authorized. Syrett, pp. 193-194 (Sections 5-7 of the Act).

[7] The Militia Act of 1862, also approved on July 17, 1862, made this authority even more explicit. Militia Act of 1862, U.S., Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America, vol. 12 (Boston, 1863), pp. 597–600, reproduced by the Freedmen & Southern Society Project of the University of Maryland, https://freedmen.umd.edu/milact.htm.

[8] John Fabian Witt, Lincoln’s Code: The Laws of War in American History (Free Press, New York, NY, 2012), pp. 211-212 & *footnote; Goodwin, p. 468. Indeed, the Preliminary Proclamation differed significantly from Lincoln’s earlier draft, first read to his Cabinet on July 22. “Abraham Lincoln’s Draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, July 22, 1862,” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/abraham-lincolns-draft-emancipation-proclamation.

[9] Midwest Air Traffic Control Service, Inc. v. Jessica T. Badilla, et al., No. 21-867, May 2023, On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari, Supplemental Brief For The Petitioner (“[T]he Solicitor General has delivered what can only be described as a hot mess of a brief.”)

[10] The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation runs for 1,047 words; the final Emancipation Proclamation is only 708 words.

[11] Lincoln concluded this sentence with what he called a recommendation (as opposed to an order): “…and I recommend to them that in all cases when allowed they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.”

[12] Not surprisingly, the Confederate states took this view. So too did many Northern Democrats, who rode this claim to electoral victories in the Fall 1862 elections. More ominously, some opinion molders in Great Britain also adopted this view, which bode ill for a Lincoln Administration that desperately strove to keep that nation from intervening in the war. Witt, pp. 216-218; James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford University Press, New York, 1988), pp. 557-558, 560; Howard Jones, Union in Peril: The Crisis Over British Intervention in the Civil War (The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, 1992), pp. 175-176; William Lee Miller, President Lincoln: The Duty of a Statesman (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY, 2008), pp. 267-268.

[13] Even then, it was Salman P. Chase, Lincoln’s Treasury Secretary (and a lawyer) who had suggested this final language invoking both the Constitution and justice. Roger Lowenstein, Ways and Means: Lincoln and His Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War (Penguin Books, New York, NY, 2022), p. 167.

Thoughtfully analyzed and written, Kevin. I am currently working on a book review assignment from ECW of a new book on the Emancipation Proclamation, so I have some familiarity with your topic. While my review will not be as elegantly drafted as your article, I hope it will survive book review editor Tim Talbott’s judicious scrutiny.

Thank you kindly. I look forward to your book review.

Excellent examination of President Lincoln’s self-doubt and “second thoughts” in relation to issuing the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863.

Carl Sandburg also attempted to come to grips with Abraham Lincoln’s “delay and indecision” with releasing a final version of the Emancipation Proclamation in Chapter 34 of “AL: The War Years.” But, also consider the following elements:

• 1858 During the Lincoln/ Douglas Debates Lincoln expressed his aversion to slavery;

• 1860 The Republican Party Platform denounced the expansion of slavery internally within the United States; and considered reopening the Atlantic Slave Trade to be a crime. Yet, the same party platform committed the Republican Party to uphold the principles of The Declaration of Independence and The Constitution;

• January 1861 Kansas admitted to Union as Free State;

• August 1861 Major General Fremont issues proclamation freeing slaves in Missouri; President Lincoln has that proclamation rescinded;

• February 1862 The slave ship operator Nathaniel Gordon put to death after President Lincoln denied his request for a pardon;

• 16 April 1862 Slavery abolished in the District of Columbia;

• 22 AUG 1862 Letter of Lincoln to Horace Greeley: “If I could save the Union without freeing a single slave I would do it…”

• 20 June 1863 West Virginia admitted to Union as Slave State.

It becomes apparent that OPPORTUNITY and TIMING were recognized by Abraham Lincoln as crucial to advancing his personal agenda of “ending slavery” …telegraphed during the Lincoln/ Douglas Debates of 1858.

Many Thanks for introducing this thought-provoking topic.

Mike, thank you. All good points, and worth remembering.

Times change. The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was iisued because the Army of the Potomac finally won a battle, the Battle of South Mountain, MD, September 14, 1862, forcing Lee and his army out of Maryland. Lincoln was the most hated President in American history. This article only continues that scenario.

FDR was the most hated president in American history…by the Germans.

Lincoln was the most hated president? He won two presidential elections. Was he hated by slave owners? Sure. Those people. If I had to be hated by someone, I guess I would be doing something right if I was hated by a bunch of human traffickers, especially because I was opposed to human trafficking.

An excellent write up.

In any discussion of Lincoln and Black colonisation, one must draw the line over which he crossed by his evolvement from advocating for it as originally the ‘first branch’, which was focused as a way of actioning an alternative form of White supremacy (as up to his August 1862 meeting at the White House with leaders of the Black American community in Washington DC), to that of the ‘second branch’; it being a way of arraying ‘equality abroad’ for Black Americans with their White American colleagues.

From about 1783 to the start of WWII, White Americans who decamped the USA didn’t see themselves as doing this; rather, they saw themselves, were generally seen by their government, fellow Americans who stayed behind and above all, by the authorities of the lands where they settled as ‘bringing America to the world’.

The examples of this, by both White and Black Americans (surprisingly commonly at the same time), are nigh endless (what is now Southern Ontario just prior to the War of 1812 and as a result of the Underground Railroad; the Eureka Stockade on the goldfields of Victoria, Australia; Vancouver Island & British Columbia during the Cariboo Gold Rush, etc).

Railroad tycoon, Cornelius Van Horne, is a rare exception in this.

It’s very likely Lincoln believed in Black colonisation to the end of his life; but the prism he viewed it through changed radically.

Thank you, Hugh, for your insightful observations. Both Lincoln, and colonization in all its iterations, are complicated subjects.

Quite right they are. As short proof of the ‘Second Branch’ of Black Colonisation, I proffer the attendance of Schuyler Colfax, then-the Speaker of the House of Representatives in Congress (later Grant’s Vice President), in Victoria, colony of Vancouver Island, and the substance of his discussions with Mifflin Wistar Gibbs (brother of Jonathan Clarkson Gibbs), leader of the expatriate Black American settler communities to the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia on the West Coast in July of 1865.

Though the above timeframe and text would appear to suggest Andrew Johnson as President, it clearly is actually referencing Lincoln, whom had voiced support for impartial suffrage as appear here in both private and in his last public speech on 11 April 1865.

Why would Colfax, a clear representative of the Lincoln administration, have such an audience with ex-pat Black Americans and such intense dialogue over the American voting rights and processes, if this group was in a foreign country? The key line is, “…[Colfax] closed his remarks by desiring the coloured people [of these colonies] not to consider the Administration to be inimical to their welfare…”

Sources:

-‘Daily British Colonist’, 29 July 1865 [colonies of Vancouver Island & British Columbia].

-Gibbs, M.W., ‘Shadow & Light: An Autobiography with Reminiscences of the Last & Present Century’, Washington, DC: Self-Published, 1902, 85-92.

https://archive.org/details/shadowandlighta00gibbgoog/page/n7/mode/2up?q=july&view=theater