Stacking Arms: The Surrender at Arkansas Post

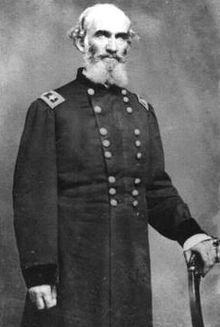

Confederate Brig. Gen. Thomas James Churchill was incredulous. The 38-year-old commander of Arkansas Post couldn’t believe his eyes. White flags of surrender were sporadically appearing along his lines and from Fort Hindman. He hadn’t ordered anyone to surrender. In fact, when it was known that a Federal attack was imminent, his departmental commander, Lt. Gen. Theophilus Holmes had told Churchill that he was expected to “hold out until help arrived or all dead.” [i] For Churchill, his command was unraveling before his eyes.

Confederate Brig. Gen. Thomas James Churchill was incredulous. The 38-year-old commander of Arkansas Post couldn’t believe his eyes. White flags of surrender were sporadically appearing along his lines and from Fort Hindman. He hadn’t ordered anyone to surrender. In fact, when it was known that a Federal attack was imminent, his departmental commander, Lt. Gen. Theophilus Holmes had told Churchill that he was expected to “hold out until help arrived or all dead.” [i] For Churchill, his command was unraveling before his eyes.

Control of the Arkansas River Valley was vital for the Confederacy. It was the gateway to Little Rock, where valuable munitions factories and ship-building facilities were located. In addition, any Union force moving down the Mississippi River towards Vicksburg had to be wary of rebel attacks from their western flank via the Arkansas River.

To defend Little Rock, in September 1862 Col. John W. Dunnington, a former officer in the Confederate States Navy, selected a location for a fort on a hairpin turn on the Arkansas River near the settlement of Arkansas Post. He constructed Fort Hindman, a square-shaped fort that had four bastions, each with emplacements for three cannons. Obstructions were placed in the river, and a line of rifle pits was constructed from the northwest bastion approximately 720 yards west to anchor at Post Bayou. [ii]

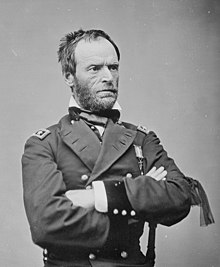

In January 1863, Union Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand arrived at Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s headquarters. Ambitious, brash, and a politically-appointed general disliked by his professionally trained peers, McClernand outranked Sherman. Both Sherman and McClernand independently devised a plan to attack Arkansas Post, but they needed help from the Mississippi Squadron under Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter.

Porter also did not like McClernand and only agreed to the plan if Sherman went along. McClernand organized his command into two corps, the XIII Corps under Brig. Gen. George W. Morgan and the XV Corps under Sherman. McClernand landed this combined force of 31,000 men downstream from Arkansas Post on January 9 and 10 to attack the fortifications on the land side, while Porter with his gunboats attacked from the river. [iii]

Facing this Union juggernaut, Churchill had 5,000 men divided into three brigades. Commanding the guns and forces in Fort Hindman was Col. Dunnington, while the rifle pits were manned by the brigades of Col. Robert Garland, with Col. James Deshler’s brigade extending the line from Garland’s left to the swampy ground at Post Bayou. Churchill’s men were largely dismounted cavalrymen from Arkansas and Texas, and most carried short-range carbines or shotguns. Due to an outbreak of disease in the Confederate camps, only 3,000 men were healthy enough to fight. [iv]

At 5:30 p.m. on January 10, McClernand told Porter his men were ready to attack. Porter sent the city-class ironclads Baron DeKalb, Cincinnati and Louisville forward to bombard the fort, while the timberclads Lexington and Blackhawk provided supporting fire. The bombardment ceased two hours later. With light fading, the fort’s guns ceased firing, and Porter decided it was too dark to accomplish anything further. To Porter’s surprise, he discovered that McClernand failed to make his attack as promised. [v]

That night Churchill received much welcomed reinforcements in the form of 200 men from the 24th Arkansas Infantry and quickly readied his men for the attack he knew was to come the next day. [vi]

Soon after daybreak on January 11, McClernand’s army moved into position to attack. Brigadier generals Frederick Steele’s and David Stuart’s divisions of the XV Corps were on the right of the line, and brigadier generals A.J. Smith’s and Peter J. Osterhaus’ divisions of the XIII Corps were on the left. [vii]

At the pre-arranged signal for the attack, at 1:00 p.m. Porter ordered the Louisville, De Kalb, and Cincinnati to churn upriver and open fire. Porter had the Rattler, Glide and Monarch pass the fort to prevent the rebels from escaping and creating a crossfire. Soon the guns of Fort Hindman had again been silenced. Around 4:00 p.m., white flags appeared on the parapets. Porter landed with his sailors and entered the fort through an embrasure. He was met by Col. Dunnington, who handed his sword to Porter and surrendered his men and the fort to the Navy. [viii]

When Sherman heard the sound of the Navy’s guns, he ordered his batteries to open fire on the Rebel lines. After 30 minutes, Sherman’s cannons ceased firing, and McClernand sent his men forward.

General Churchill’s men put up stiff resistance. On Deshler’s front the fight was desperate. His men halted one Union attack after another, and Deshler sent one regiment to his left to counter a Union attack that was attempting to turn his line in a gap between his flank and Post Bayou. Two further attacks were repulsed by Deshler, who desperately requested reinforcements from Garland. This thinned and stretched Garland’s line, which was equally hard-pressed. [ix]

Smith’s and Osterhaus’ soldiers swarmed toward Garland’s lines. “General A.J. Smith and his staff, pistols in hand, rode among the troops cursing and shouting words of encouragement. As one of the soldiers recalled, ‘for artistic, and effective profanity, General…Smith had no superior….His every word hit the nail on the head, while all the air was blue.’”[x] Despite Smith’s colorful encouragements, Garland’s men held off the blue surge for an hour and a half, not knowing that their comrades in nearby Fort Hindman had surrendered.

It was past 4:00 p.m. when someone in the Confederate ranks was heard to shout, “Raise the white flag by order of General Churchill; pass the order up the line.” [xi] But Churchill had not given the command to surrender. Frantic, Churchill rushed to the scene.

Seeing the white flags, overwhelming numbers of Osterhaus’ and Smith’s men had entered the Confederate rifle pits and ordered the Confederates to stack arms. At Smith’s sector Churchill told the Federals he hadn’t surrendered, but looking around he could see the point was moot. Churchill was introduced to Gen. McClernand, who had arrived. The formal surrender started.

On the Confederate left, Col. James Deshler saw the white flags, but did not believe it and kept his men fighting. Suddenly the Federals firing in his front stopped, and a Union officer bearing a flag of truce approached. Deshler had his men cease firing. The Union officer told Deshler that Churchill had surrendered, but Deshler still refused to believe it and prepared to fight on.

Sherman, arriving on the scene, tried to convince Deshler that the surrender was real. Sherman dispatched one of his staff officers to locate Churchill and have him rush orders to Deshler to prevent further bloodshed. Churchill arriving soon after, explained to Deshler, “You see, sir that we are in their power, and you may surrender.” [xii]

It was now past 5:00 p.m., and Sherman was ordered by McClernand to remain with his troops outside the fort. An angry Sherman thought this was a way of denying him and his troops any recognition for the victory. After all, his troops suffered the greater number of casualties in the assault. Instead, McClernand sent Gen. A.J. Smith into the fort to claim it as a prize.

Porter and his men were still in the fort when a large number of Union officers came riding in on horseback. One of Smith’s adjutants demanded, “Get out of this fort. Everybody clear this fort. General Smith is coming to take possession.” Admiral Porter, dressed in a plain blue blouse with only shoulder straps to indicate his rank, replied, “Who are you, pray, that undertakes to give such an order here? We’ve whipped the rebels out of this place, and if you don’t take care, we will clear you out also.” [xiii]

At that point, Brig. Gen. A.J. Smith rode up. The two had never met before. “Here, General,” said the adjutant, “is a man who says he isn’t going out of this fort for you or anybody else, and that he’ll whip us out if we don’t take care.”

“Will he, by God?” said Smith dismounting. “Let me see him; bring the fellow to me.”

Porter stepped forward and said, “Here I am, sir, the admiral commanding this squadron.”

At this announcement Smith’s right hand dropped to the holster of his pistol at his side. Porter thought that Smith was going to shoot him. Instead, Smith hauled out a bottle and said, “By God, Admiral, I’m glad to see you. Let’s take a drink.” [xiv]

General A.J. Smith and Admiral Porter became fast friends – a bond which lasted throughout the war. The admiral learned that Smith’s apt nickname with his troops was “Whiskey”. [xv]

Porter and Smith weren’t the only officers celebrating the fall of Arkansas Post. Forty-year-old Pvt. Solomon Woolworth of the 113th Illinois Regiment (1st Brigade, 2nd Division, XV Corps) was helping to bury the dead when he saw his regimental officers enjoying a drunken celebration. [xvi]

The Union forces lost 134 men killed, 898 wounded, and 29 missing, while Porter recorded 31 casualties. Outnumbered 10 to 1, the Confederates lost 60 men killed, 73 wounded and, once all the guns were stacked, 4,800 Confederates captured. [xvii]

Porter, Sherman, and McClernand continued to be at odds. The moment the prisoners were secured, the fort rendered untenable, and the dead buried, McClernand wrote a report of the capture claiming most of the credit for himself. In his Memoirs, Sherman reported that McClernand returned to his headquarter’s ship, the Tigress, where Sherman heard the exuberant McClernand exulting, “Glorious! Glorious! My star is ever in the ascendant! I’ll make a splendid report.” [xviii]

McClernand’s report almost ignored the action of Porter’s fleet altogether. Sherman in a letter to his brother, Senator John Sherman, insinuated that McClernand’s report was inaccurate. [xix] Later, to his wife Sherman wrote: “[McClernand is] unfit and …consumed by an inordinate personal ambition.” [xx]

Porter, however, had his revenge. Carried by his fastest steamboat, Porter’s report was on Grant’s desk before McClernand’s and was sent to Washington and the newspapers via telegraph. Porter’s report blasted McClernand’s leadership and tried to give more credit to Sherman and the Navy. Porter told Grant that he and McClernand “could never co-operate harmoniously and [that he] hoped he would come and take command himself.”[xxi] Porter in his report to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus V. Fox, wrote: “McClernand is no soldier, and has the confidence of no one. [xxii]

The surrender of Arkansas Post secured Grant’s flank on his drive to Vicksburg and boosted the morale of Union forces after their defeat at Chickasaw Bayou. As one historian pointed out, “The defeat at Arkansas Post cost Confederate Arkansas fully one-fourth of its armed forces in the largest surrender of Rebel troops west of the Mississippi River prior to the final capitulation of the Confederacy in 1865.” [xxiii]

[i] Bearss, Edwin C., The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. I: Vicksburg is the Key, Dayton, Ohio, Morningside Press, Inc., 1985, pp. 379, 402. Chatelain, Neil P., Defending the Arteries of Rebellion: Confederate Naval Operations in the Mississippi River Valley, 1861-1865, El Dorado, California, Savas Beatie, 2020, p .211

[ii] Shea, William L & Winschel, Terry J., Vicksburg is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River, Lincoln, Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press, 2003, p. 56. Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, pp. 350-351

[iii] Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, p. 363. Kiper, Richard L., Major General John Alexander McClernand: Politician in Uniform, Kent, Ohio, Kent State University Press, 1999, p. 161.

[iv] Shea & Winschel, Vicksburg is the Key, p. 56. Chatelain, Defending the Arteries, p. 210.

[v] Arkansas Post, Battle of – Encyclopedia of Arkansas Article by Mark K. Christ, July 2, 2024

[vi] Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, p. 373.

[vii] O.R. Ser. I, Vol. XVII, pt. I, p. 706.

[viii] O.R.N., Ser. I, Vol. 24, pp. 108-117.

[ix] Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, pp. 381-383. Smith, Timothy B., Bayou Battles for Vicksburg: The Swamp and River Expeditions, January 1-April 30, 1863, Lawrence, Kansas, University Press of Kansas, 2023, p. 56

[x] Bearss, The Campaigns for Vicksburg, pp. 383-401

[xi] O.R., Ser. I, Vol. XVII, pt. 1, p.785.

[xii] Sherman, William Tecumseh, Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman, The Library of America, reprint, New York, 1990, pp. 321-323.

[xiii] Porter David Dixon, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War, New York, Appleton, 1885, p. 214. Kiper, McClernand, pp. 175-176.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Eicher, John H. & Daniel J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands, Redwood City, California, Stanford University Press, 2001. p. 492

[xvi] Bierle, Sarah Kay, Battle of Fort Hindman: “Then Went Into Charge”, Emerging Civil War website, Jan. 16, 2023. Woolworth, Solomon, Experiences in the Civil War, 1903, pp. 3-4. Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/o3025277/.

[xvii] Bearss, Campaign for Vicksburg, p. 405 www.nps.gov/arpo/learn/historyculture/upload/battle-of-ARPO-Booklet.pdf Huffstot, Robert S., “The Battle of Arkansas Post,” Civil War Times Illustrated, Jan., 1969. OR, series I, vol. XVII, pt. I, p. 782

[xviii] Sherman, Memoirs, p. 324

[xix] Thorndike, Rachel Sherman, ed., The Sherman Letters: Correspondence between General and Senator Sherman from 1837 to 1891, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1894. pp. 181-182.

[xx] Sherman to Ellen Boyle Sherman, 16 Jan. 1863, Sherman Family Papers, University of Notre Dame,

[xxi] Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes, p. 148. No such message has been located, although Grant in his memoirs mentions having received such a recommendation from Porter and Sherman.

[xxii] Thompson, Robert Means, and Richard Wainwright, eds., Confidential Correspondence of Gustavas V. Fox, 2 vols., New York, DeVinne Press, 1920. p.154.

[xxiii] Arkansas Post, Battle of – Encyclopedia of Arkansas Article by Mark K. Christ, 2024.

Interesting story on an important but not well known action.

Thank you, Kevin.

After John McClernand’s meeting with President Lincoln (memorialized in a CDV taken at Antietam Maryland featuring Major General McClernand to Lincoln’s left, and Allan Pinkerton to Lincoln’s right) McClernand was given a command independent of Major General Grant and sent west end of 1862 to “take Vicksburg.” McClernand was subsequently persuaded by William Tecumseh Sherman that Vicksburg could not be taken with the force at McClernand’s disposal; so the attack was made against Arkansas Post, instead. There was more political maneuvering involved in this one campaign than any since George McClellan was removed, reinstated, and removed from command again.

Thank you, Mike, for your feedback. I whole-heartedly agree with all of the political machinations that McClernand exerted for his commission and what followed as you aptly point out.