Major General Francis Channing Barlow and the 1875 Concord Centennial

ECW welcomes guest author Andrea Quinn. This article is a companion to the article “Francis Channing Barlow: Chief Marshal of Concord’s Centennial” featured on Emerging Revolutionary War.

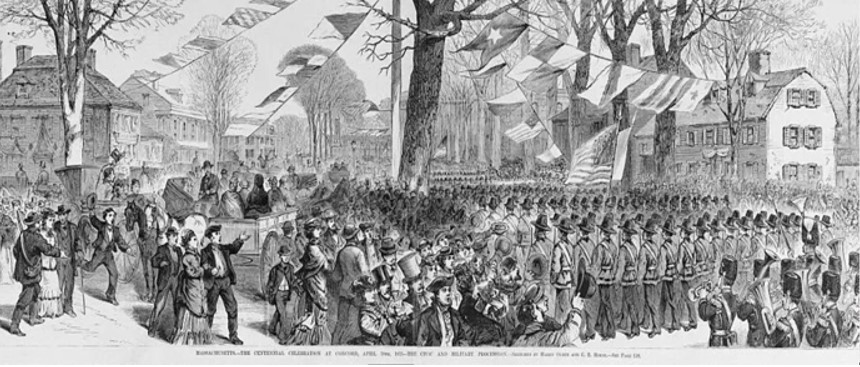

In April 1875, the town of Concord, Massachusetts, held a centennial celebration to commemorate the first battle of the American Revolution. Leading the parade was Union general Francis Channing Barlow. Appointed chief marshal, Barlow’s presence symbolized a bridge between Concord’s revolutionary past and the nation’s recent Civil War.

Though born in Brooklyn, New York in 1834, Barlow spent formative years in Massachusetts. After his parents separated, his mother, Almira, raised her sons with ideals rooted in reason and reform. Barlow attended Brook Farm, a Transcendentalist community emphasizing cooperative labor, education, and moral development. He earned the nickname “crazy Barlow” for his intense dedication to his interests. After Brook Farm, the family settled in Concord. There, Barlow became acquainted with Emerson, Hawthorne, Ripley, and Alcott—figures whose civic and moral values deeply influenced him.

By the Civil War’s outbreak, those values were fully embedded in Barlow’s character. He graduated first in his Harvard class in 1855 and began practicing law in New York. When war came, he enlisted in the 12th New York Militia. Rising from private to general, he was known for fearless leadership and strict discipline. At Antietam, he was seriously wounded. He was later wounded again at Gettysburg while commanding a division north of town. Barlow’s bond with Concord endured, as during recovery from battlefield wounds, he returned to his childhood home to convalesce. At Spotsylvania’s “Bloody Angle,” he led his men in brutal close combat. Colonel John Black recalled, “I never remember seeing General Barlow so depressed as he was on leaving General Hancock’s Headquarters… very different from the brusque and decided manner usual from him.”

Equally formative was his marriage to Arabella Griffith, a Sanitary Commission nurse ten years his senior. Independent and principled, Arabella shared Barlow’s moral convictions and often worked near the front lines. Their relationship defied expectations but was grounded in mutual respect. Her death from typhoid fever in 1864 devastated him, leading to an extended leave from the war. Concord’s quiet fortitude restored Barlow’s spirit and helped him grieve the death of his beloved wife, Arabella, in July 1864.

After the war, Barlow resumed public service. He served as New York’s Secretary of State, U.S. Marshal, and later Attorney General, where he led the prosecution of William “Boss” Tweed. In 1867, he married Ellen Shaw, sister of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. This renewed his ties to reformist and abolitionist circles. The couple had three children, including a daughter, Louisa, born on July 27, 1873—the anniversary of Arabella’s death.

Barlow’s background and integrity made him an ideal choice for Concord’s centennial. The committee, chaired by George Keyes, sought someone who could symbolize both Concord’s revolutionary spirit and the Union’s recent struggle. In February 1875, Barlow accepted the appointment, writing: “I feel flattered at being so remembered and I will with great pleasure act as the Chief Marshal.”

He took the role seriously—corresponding with national figures, organizing the procession, and ensuring the event reflected unity and meaning. He approached the responsibility with the same discipline that had guided his military and civic service.

On the day of the celebration, Barlow led the parade on horseback, solemn and composed. Veterans of both the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, militia units, officials, and townspeople followed. It was a powerful display of national continuity. Barlow—twice wounded in defense of the Union—embodied the ideals first kindled in Concord.

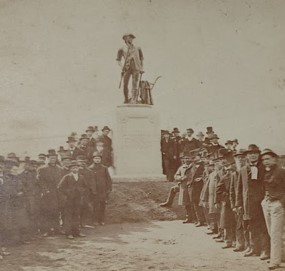

One of the most poignant moments was the unveiling of the Minute Man Monument by 25-year-old sculptor Daniel Chester French. His first major commission, the statue—cast from melted Union cannons—depicted a colonial farmer stepping from his plow to take up arms. It quietly embodied civic responsibility and echoed Barlow’s own transformation from citizen to soldier.

Barlow’s leadership lent dignity to the day, while the speakers added emotional depth. George William Curtis, a reformer and Barlow’s brother-in-law, offered a memorable address, noting that Concord’s lesson was not bloodshed, but the triumph of an idea.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, who had influenced Barlow as a youth, offered an invocation: “Spirit, that made those heroes dare to die… bid time and nature gently spare the shaft we raise.” James Russell Lowell, related to Barlow through Charles Russell Lowell, reflected: “They were men who did not seek greatness but met it when it called.” True to form, Barlow remained in the background. In his acceptance letter, he wrote, “You will be surprised to hear that … I have never been able to overcome my horror of making after dinner speeches.”

Even in silence, Barlow’s presence spoke volumes. Once a youth shaped by Concord’s ideals, he had become one of its most honorable sons—standing as a decorated general, civic reformer, and symbol of duty and sacrifice.

The centennial reminded Americans that liberty, born in 1775, had to be defended again in 1861. In Francis Channing Barlow, Concord honored both eras. He quietly reminded the nation that the spirit of 1775 still lived in those who rose when called.

Francis Channing Barlow died on January 11, 1896, and is buried in Walnut Street Cemetery in Brookline, Massachusetts. His life—of war, reform, and remembrance—found fitting expression at the Concord Centennial, where he helped his country not just recall its origins, but reassert its ideals.

Bibliography:

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. The Conduct of Life. Houghton Mifflin, 1860.

Thoreau, Henry David. Walden. Ticknor and Fields, 1854.

Gross, Robert A. The Minutemen and Their World. Hill and Wang, 1976.

Richardson, Robert D. Emerson: The Mind on Fire. University of California Press, 1995.

Barlow, Francis C. The Barlow-Gordon Letters: A Civil War Dialogue Between Friends. Edited by Frank J. Wetta, University Press of Kansas, 2009.

History of Concord. Concord Free Public Library, https://concordlibrary.org.

Centennial Celebration Records, 1875. Town of Concord Archives Collection.

Apocrypha Concerning the Class of 1855 of Harvard College and Their Deeds and Misdeeds During the Fifteen Years Between 1855 – 1880 by Edwin Abbot, Class Secretary, Boston, Alfred Mudge & Son, Printers, 34 School Street.

Andrea M. Quinn holds a Bachelor’s degree in History and Secondary Education from Bridgewater State University and an Executive Healthcare Certificate from Cornell University. With over 34 years of experience, she currently serves as an Executive Director for a large healthcare organization in Massachusetts. Andrea is a board member of the Sandy Bay Historical Society in Rockport, Massachusetts, co-chair of the First Parish Cemetery restoration project. Her article, “My Beloved Arabella,” was published in the February 2024 issue of Gettysburg Magazine.

Barlow figures prominiently in my new book, “Lee Besieged: Grant’s Second Petersburg Offensive, June 18-July 1, 1864,” due out momentarily from Savas Beatie. He also figured prominently in an earlier book of mine, “The Siege of Petersburg: The Battles for the Weldon Railroad, August 1864 (Savas Beatie, 2015).

For all his undoubted bravery in battle, Barlow’s inherent superciliosness, an unfortunate but predictable byproduct of his upbringing, made him a problematic general of volunteers. This was particularly true for those not native born. Never a fan.

Typical

Barlow is the model for the Union officer in Winslow Homer’s “Prisoners from the Front”

Barow

Rev War Veterans in ceremony? Believe last one died in 1868.

Barlow is the Union officer in Winslow Homers Prisoners From the Front

Ms. Quinn has provided a very well written and insightful piece on Barlow. I enjoy standing on “his”(Blocher) Knoll and look back towards Oak Hill. I see why he was attracted to the elevation.

Thank you for your kind words