Col. Percy Wyndham Memorialized in Myanmar

On January 25, 1879, spectators packed into Dalhousie Park in Rangoon (now Yangon) to witness Col. Percy Wyndham ascend in a custom-made, 70-foot-tall hot-air balloon. All went as planned until he reached 500 feet, when the balloon suddenly exploded, sending the intrepid aeronaut plummeting into Kandawgyi (Royal) Lake at high speed to his death.

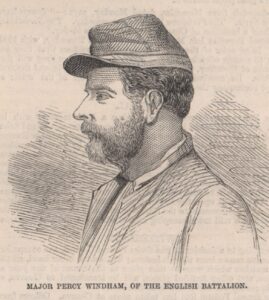

Today, Wyndham is perhaps best remembered by Civil War aficionados for his magnificent facial hair — a winged handlebar mustache paired with an extended ducktail beard — styled with who knows how many tins of wax.

One Indiana newspaper reporter, who claimed to have known Wyndham well, described him as “swaggering, loud spoken, with a tremendous mustache and a general air of braggadocia [sic].”

Wyndham, the son of a British cavalry officer, was born aboard a ship en route to India and baptized in Calcutta (now Kolkata). Given his birth on the high seas, it’s not surprising that he never settled anywhere for long and chose the profession of soldier-adventurer. Wyndham served in the French Navy and spent eight years as a second lieutenant in the Austrian Army before joining Giuseppe Garibaldi’s campaign in Italy. He distinguished himself at the battle of Milazzo while serving as a major in the English battalion. For his service, he was named a Knight of the Military Order of Savoy.

In 1861, Wyndham traveled to the United States to fight in the Civil War. In February 1862, New Jersey Gov. Charles S. Olden appointed him colonel of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry. On June 6, at the battle of Good’s Farm, Wyndham was captured by Confederate troopers after his horse was shot out from under him during an imprudent charge. He was paroled in August and wasted no time in returning to his command.

Wyndham’s brigadier, George D. Bayard, detached him to command a brigade at Chantilly. However, Wyndham drew the ire of officers under his command when he severely criticized Col. Nathaniel P. Richmond of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry for refusing to conduct a reconnaissance mission to investigate a railroad bridge the rebels were supposedly constructing at Rappahannock Station. Richmond cited “informality and the want of rations” as his reasons. Wyndham called Richmond a coward and allegedly struck him in a fit of rage. Richmond was arrested, while Wyndham avoided any charges for his actions.

In January 1863, Wyndham submitted his resignation to the department commander, Maj. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman, after being ordered to serve under Col. Richard B. Price, “who, in my opinion, is incompetent and for whom I cannot feel the proper respect.” Heintzelman instead suggested that Wyndham be transferred back to his regiment.

“Col. Wyndham is such an excellent Cavalry officer, when under the orders of a suitable commander, and has behaved so gallantly on frequent occasions, that I would most reluctantly see his resignation accepted,” Heintzelman wrote. “His services with the main army in the front, would, I am satisfied, be eminently valuable.”

By March, after his failure to capture Col. John S. Mosby, Wyndham was relieved and reassigned to the 1st New Jersey Cavalry.

On June 9, 1863, during the cavalry clash at Brandy Station, Wyndham was shot in the right leg and consequently missed the iconic battle of Gettysburg the following month. While recovering, he assembled a force of roughly 2,600 men to help defend Washington, D.C., from Gen. Robert E. Lee’s invading Army of Northern Virginia.

On September 26, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker recommended the colorful, but difficult Englishman for promotion to brigadier general. “I found him capable, prompt and efficient in the execution of orders, and with an enemy in his front enterprising and brave,” Hooker wrote in his recommendation to President Abraham Lincoln.

Just six days later, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton telegraphed Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, stating that Wyndham should not be allowed to hold command or even come within the lines of the Army of the Potomac. Although Wyndham had already returned to his unit, Stanton ordered him to relinquish command and report to the capital.

Wyndham sought a court of inquiry and requested reinstatement. Though lacking official permission or a formal command, he returned to the army, eager to get back into the fight. On one occasion, he led a cavalry squad during a skirmish while scouting rebel positions. In June 1864, Wyndham was taken into custody and escorted back to Washington, D.C. He never received a promotion to brigadier general nor another assignment, and he was quietly mustered out of the army in July.

A rumor, perpetuated by Col. Henry Charles De Ahna in October 1863 and shared with Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, claimed that Wyndham intended to surrender his command for a hefty prize. (Ironically, when Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck heard that De Ahna had been nominated for brigadier general, he remarked, “I would rather trust my dinner to a hungry dog than give such a responsible position to a foreign adventurer of this stamp. I have not the least doubt he would take pay on either side and fight on none.”)

Another dubious report, published in 1867 by a correspondent for the New York Herald, circulated claims that certain parties in Canada alleged Wyndham had plotted to abduct President Lincoln and his cabinet and turn them over to the Confederates.

Neither of these accusations was ever substantiated.

A glory hunter, Wyndham craved accolades — something money couldn’t buy — and he demonstrated this through his persistence, and even insubordination, in seeking to return to the front. It is far more plausible that Stanton had blacklisted Wyndham because he had grown tired of the Englishman’s antics and no longer trusted him, rather than because Wyndham had participated in a scheme to betray his troops or kidnap Lincoln.

Beloved? No. Traitor? Hardly convincing.

After the war, Wyndham opened a fencing school in New York City, but returned to Italy to aid Garibaldi when war resumed in 1866. In 1872, he went back to India and launched a satirical magazine, The Indian Charivari. Poor investments eventually prompted him to move to Myanmar (then Burma), where he reportedly offered his services to King Mindon Min to help modernize the Burmese Army.

According to contemporary newspaper accounts and burial records, Wyndham’s remains were recovered from the balloon wreckage and interred at Rangoon’s Town Cemetery. Like many foreign graves in Rangoon, the Burmese government later cleared the cemetery’s headstones, erasing any trace of the burial sites. A family monument in Cockermouth Cemetery, England, briefly mentions Wyndham’s birth and death dates. However, there is no record of his remains being returned to England or interred in that cemetery alongside his parents.

Fortunately, Wyndham qualified for a U.S. government-issued veteran memorial marker. Yeyway Cemetery generously allowed the placement of a bronze memorial niche on its grounds to honor Wyndham.

Honoring an American Civil War veteran buried in Myanmar (formerly Burma) — or anywhere in Southeast Asia, for that matter — is a rare opportunity. After more than 140 years and roughly 8,500 miles from the United States, the brave, yet controversial Percy Wyndham is finally recognized for his military service.

Shrouded Veterans is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to rescuing the neglected graves of 19th-century veterans, primarily Mexican War (1846-48) and Civil War (1861-65) soldiers, by identifying, marking, and restoring them. You can view more completed grave projects at facebook/shroudedvetgraves.com.

Thank you for this very much. Thank you for your enterprising efforts obtaining that photo of the well deserved memorial.

Appropriate that this gasbag died in a gasbag!