Book Review: Military Captives in the United States: A History from the Revolution Through World War II

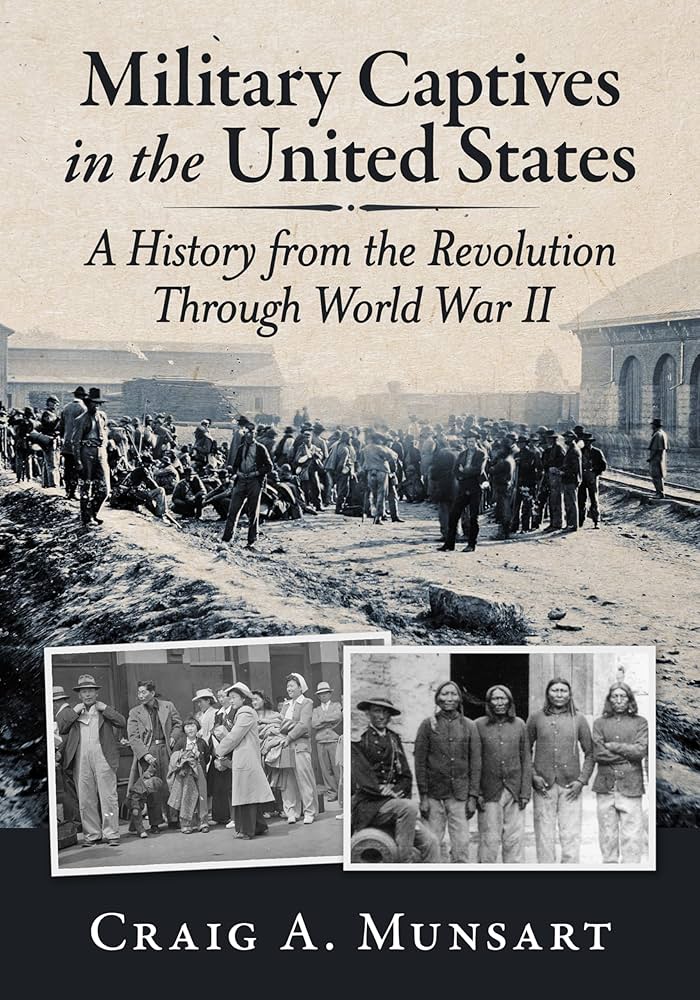

Military Captives in the United States: A History from the Revolution Through World War II. By Craig A. Munsart. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Incorporated Publishers, 2025. Paperback, 303 pp. $49.95.

Military Captives in the United States: A History from the Revolution Through World War II. By Craig A. Munsart. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Incorporated Publishers, 2025. Paperback, 303 pp. $49.95.

Reviewed by Greg Romaneck

“As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror . . . before us were forms that had once been active and erect-stalwart men, now nothing but merely walking skeletons . . . many of our men exclaimed with earnestness, ‘Can this be hell?’” (26) These fearful words represent Union prisoner Robert H. Kellogg’s introduction to Andersonville, one of the deadliest among the many vile places that prisoners of war were kept during the Civil War. It is places such as Andersonville that Craig A. Munsart writes about in his comprehensive efforts to chronicle the fate of not only Civil War prisoners of war, but also those held within the confines of the United States during the many other wars that Americans have fought.

In telling the story of prisoners of war across America’s conflicts, Munsart takes on a wide-ranging subject and does so in a capable manner. Approximately 20 percent of Munsart’s book directly deals with Civil War prisoners. A further 10-15 percent encompasses the fate of Native Americans who fought their own civil war against the inexhaustible advancement of white Americans into their territories during the Civil War years. The remainder of the book addresses the fate of prisoners held in the U.S during other conflicts including, but not limited to, the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and both World Wars.

Each chapter of Munsart’s book goes into some depth regarding factors such as prisoner exchange processes, the treatment of captives, the often horrific conditions in prisons, the fate of political prisoners, and how prisoner repatriation sometimes occurred. In each case, Munsart does a good job of piecing together primary and secondary sources to give his readers an introductory understanding of the fate of prisoners of war in most of America’s wars.

As far as Munsart’s depiction of Civil War prisons alone, readers will come away from this book with either a refreshed or introductory understanding of how it became possible for Americans to treat one another in so foul a manner as was represented in the global approach both opposing sides used when handling prisoners of war. In his introduction Munsart justly describes the generally wretched treatment Civil War prisoners of war received in a way that should leave readers shaking their head over the fate of those poor inmates: “During the Civil War Americans in POW camps were treated more brutally than POWs from any other countries in American history; captives in other wars may have suffered more intense tortures, but Civil War tortures were from the camps themselves.” (19)

In terms of the author’s approach to describing Civil War prisons, and the way prisoners in general were handled, Munsart does well to detail the arcane exchange mechanisms that were initially used to handle the unexpected influx of tens of thousands of prisoners. During the Civil War, neither side predicted a long and relentless struggle that could possibly yield up an overwhelming number of prisoners. That harsh reality, as Munsart notes, led to inconsistent exchange practices that broke down in the face of large numbers of prisoners of war. What followed was a descent into cruelty and barbarism that was lived out in places such as Point Lookout, Libby, Andersonville, Elmira, and Camp Douglas. By war’s end, as Munsart notes, “670 thousand prisoners were taken, 250 thousand were exchanged, and 248 thousand were paroled. The rest died in prison or were released.” (36) In this way, and with a degree of savagery that is hard to understand, over 50,000 Union and Confederate soldiers or sailors perished in ways that should never have occurred.

While tens-of-thousands of Union and Confederate prisoners were languishing in a various hellholes labeled as prison camps, a whole other military struggle was being waged in the West. There, during the Civil War years, a pitiless struggle took place between Native Americans and both opposing sides of the Civil War. While the treatment of Civil War prisoners in the East was generally brutal, the way war captives were treated in the West was perhaps even more tragic. In his chapter on the “Indian Wars,” Munsart describes the overarching suffering that was inflicted by and upon Native Americans in what can truly be seen as a portion of a decades-long genocidal conflict.

It is this inhumane approach to prisoners of war that remains a dark shadow cast within the broader suffering that was America’s Civil War. While not purely a Civil War book, Munsart’s history of American prisoner of war facilities is a worthwhile study and one that, despite its high price-tag, is worth consulting. While not a groundbreaking book, Munsart’s writing is solid, and the story he tells is one worthy of attention regarding a tragic chapter in Civil War history.

Greg M. Romaneck is retired after working for 34 years as a professional educator and consultant. During those years he held positions such as special education teacher, assistant principal, elementary principal, adjunct professor, director of special education, student teaching supervisor, and associate superintendent. Mr. Romaneck has also trained as a counselor and worked in areas such as crisis intervention, mediation, problem solving, and conflict resolution. Greg has had several books and numerous articles published on a variety of subjects such as Education, Psychology, Self-Improvement, Backpacking, Eastern Philosophy, Civil War history, Poetry, and Bible studies. Greg has also had nearly 3,500 book reviews published by Childrenslit.com, a popular source of information for educators, librarians, and parents regarding books for younger readers and has reviewed Civil War books for four decades for a variety of publications and magazines. Most recently Greg was the featured book reviewer for more than a decade with the Civil War Courier. Greg resides in DeKalb, Illinois and enjoys spending time with his family & friends, hiking, kayaking, backpacking, reading, and writing.