Breathing Life into the Past: Enhancing Civil War Portraits with Artificial Intelligence

ECW welcomes guest author M.A. Kleen.

The American Civil War left behind a vast photographic legacy, thousands of glass plate negatives and albumen prints capturing the likenesses of soldiers, officers, civilians, and battlefields. Often faded, damaged, or grainy, these portraits have remained locked in the visual language of the 19th century: solemn faces frozen in grayscale or sepia tones.

But recent advancements in artificial intelligence have begun to unlock new possibilities for engaging with this history, offering digital tools that restore, enhance, and colorize these images with startling realism.

Artificial intelligence isn’t just sharpening blurry edges, it’s reshaping how we connect with the past. A clear, colorized image of a young Union soldier or a Confederate general standing in full uniform can elicit a powerful emotional response. These enhancements bridge a perceptual gap that black-and-white photography often maintains, turning distant, ghostly visages into something more relatable: living, breathing people who once lived as we do, in full, vivid detail.

Traditional manual colorization of black-and-white images, often done in software like Adobe Photoshop, is time-consuming and frequently yields lackluster results. The colors can appear dull and uniform, with mismatched palettes creating a distracting “painted-on” look rather than enhancing the image.

Like any technology, AI tools like OpenAI’s ChatGPT are constantly evolving. While they offer exciting potential benefits, they also present drawbacks. Researchers must carefully balance these benefits against their limitations.

At first glance, the benefits are obvious. AI-driven tools can, in seconds, improve photo contrast, correct physical damage, remove scratches or stains, and even generate plausible color schemes based on contextual data. The result is often a dramatically clearer, more lifelike image. Uniform buttons gleam, eyes regain their focus, and textures from wool to brass reappear with surprising accuracy. This makes uniforms, facial features, and battlefield scenes more interpretable.

It has other uses as well. Websites like Civil War Photo Sleuth use AI-powered facial recognition to match unidentified portraits with known soldiers, revealing names behind anonymous faces. Since 2018, more than 30,000 Civil War photos have been added and over 3,300 identifications made, with an impressive accuracy of 75-80 percent.

I have successfully colorized and upscaled Civil War portraits using AI tools like ChatGPT and Real-ESRGAN. Even with minimal prompting, the results are promising, especially with higher-resolution originals. While starting with a better image yields the best outcome, ChatGPT can still produce impressive results from low-resolution black-and-white photos.

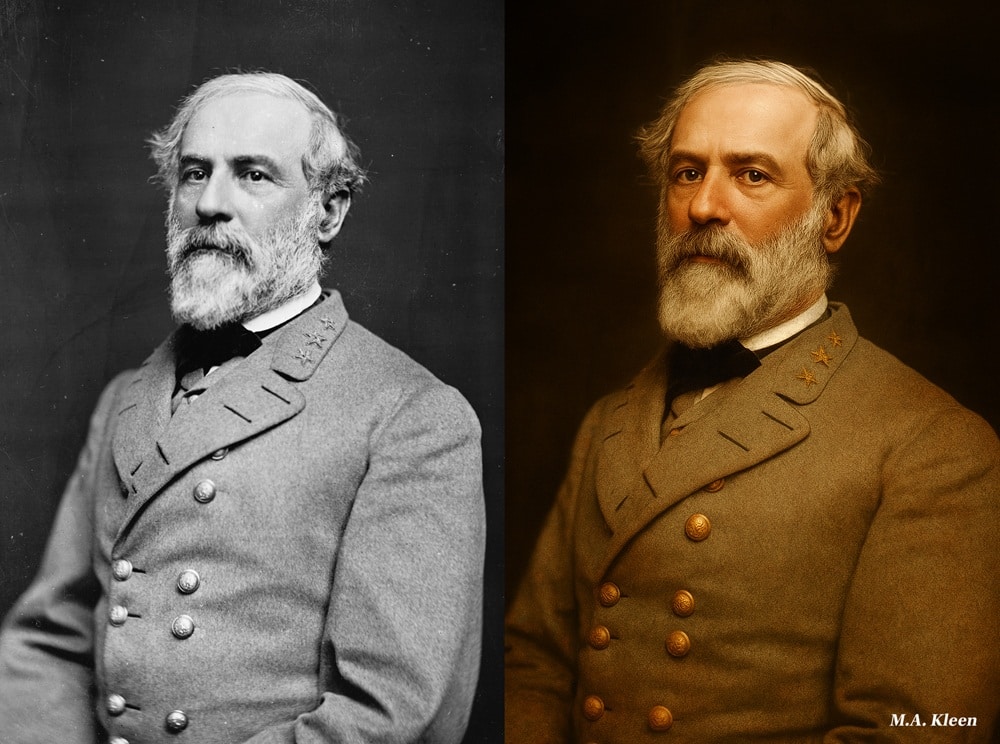

I enhanced this portrait of Robert E. Lee[1] using ChatGPT and the prompt “Enhance the attached photo of a Confederate Civil War general Robert E. Lee wearing a gray uniform, colorize and make it realistic. Retain every detail and photo dimension exactly as is. Make sure his face is identical to the photo. His hair is gray to white and his eyes are dark brown.”

I enhanced this portrait of Robert E. Lee[1] using ChatGPT and the prompt “Enhance the attached photo of a Confederate Civil War general Robert E. Lee wearing a gray uniform, colorize and make it realistic. Retain every detail and photo dimension exactly as is. Make sure his face is identical to the photo. His hair is gray to white and his eyes are dark brown.”

The results using this high-resolution image are impressive but not an exact one-to-one likeness.

I then enhanced the above low-resolution portrait of Union Gen. George H. Thomas[2] using the prompt “In the same style as above, enhance and colorize the attached photo of a civil war Union general. Don’t change any detail about his face or uniform. Keep the same photo dimensions.”

Likely because the starting image was such poor quality, ChatGPT hallucinated more details, including a row of buttons on his left sleeve, hands, and a different style of belt. Still, it is a recognizable image of “The Rock of Chickamauga.”

The above comparisons reveal the limitations of these AI tools. Imperfections, fabricated details (“hallucinations”), and artistic interpretations prevent a truly accurate one-to-one comparison with the original. While AI can get very close, a perfect replication remains elusive.

The above comparisons reveal the limitations of these AI tools. Imperfections, fabricated details (“hallucinations”), and artistic interpretations prevent a truly accurate one-to-one comparison with the original. While AI can get very close, a perfect replication remains elusive.

This is because AI relies on educated guesses based on its training data. A Confederate general’s gray wool coat might be convincingly restored, but details like the exact shade of a belt buckle or the precise form of a brigadier general’s laurel wreath rank insignia might be approximated or even distorted. While AI can simulate realism, it doesn’t guarantee historical accuracy. This tension between enhancement and invention represents both the potential and the risk of this technology.

When critiquing these results, we should keep in mind that photography is a creative pursuit as well. Portraits, in particular, idealize their subjects, rarely capturing their everyday appearance. Lighting, posing, cosmetics, and darkroom techniques using various chemical developing agents, manual retouching, dodging, and burning all shape the image to fit the photographer’s artistic vision. Just like AI-enhanced images, traditional photographs, as Richard Avedon famously observed, don’t perfectly replicate a person’s likeness.[3]

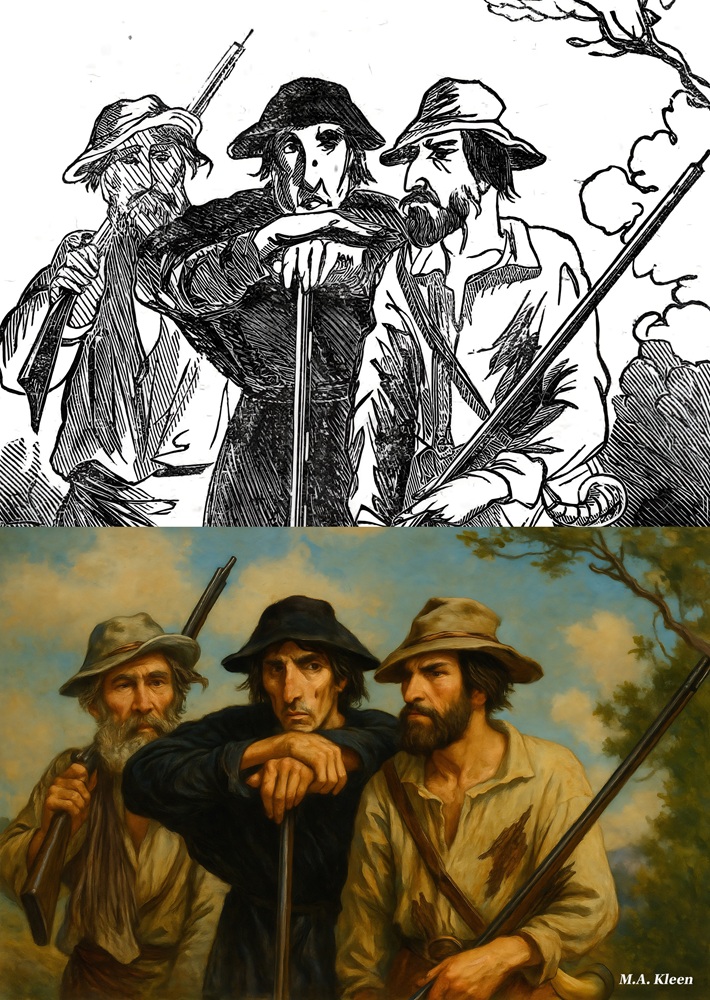

AI can also be used to transform Civil War-era illustrations as well. In the next example, I asked ChatGPT to enhance an illustration of Confederate volunteers from the mountains of northwest Virginia in Charles Leib’s book Nine Months in the Quartermaster’s Department (1862).[4] The algorithm was able to successfully take a rough sketch and create a lifelike scene.

Doing so, however, erases the illustrator’s original intent, which was likely a satirical caricature. The men appear more heroic and determined, and their exaggerated features are toned down. Viewers unfamiliar with the original artwork may interpret the enhanced image as a literal, historically accurate scene, which it is not.

Doing so, however, erases the illustrator’s original intent, which was likely a satirical caricature. The men appear more heroic and determined, and their exaggerated features are toned down. Viewers unfamiliar with the original artwork may interpret the enhanced image as a literal, historically accurate scene, which it is not.

Researchers should also be mindful of the evolving policies surrounding AI image generation and modification. My own experiments with historical image enhancement in ChatGPT revealed OpenAI’s sometimes inconsistent rules. While enhancing Civil War portraits is generally allowed, the same process is often blocked for other historical images.

OpenAI’s rationale is that Civil War portraits, being formal and documentary-style rather than expressive or narrative, are treated as historical artifacts. Thus, transformations are considered restoration, not expressive alteration. Colorizing and modifying portraits of generals like Robert E. Lee or George B. McClellan is acceptable, but similar enhancements to historical figures in more expressive poses are often prohibited as “creative content.”

The line between permissible and prohibited is fine and seemingly arbitrary. While these policies aim to prevent misuse of likenesses and the creation of misleading content, their rigid application can lead to illogical outcomes. Formal studio portraits are deemed “safe,” while other public domain photos of deceased individuals are flagged as too risky.

Despite its limitations, AI enhancement offers clear benefits. It revitalizes historical records, improves educational resources, and connects modern audiences with the past. It also democratizes restoration, providing powerful tools to historians, educators, and enthusiasts who may lack access to expensive software or specialized training.

However, the drawbacks are equally important. AI can introduce subtle inaccuracies that accumulate into misleading representations. An enhanced photo might be clearer, but less accurate. A colorized uniform might look authentic but reflect modern expectations rather than historical truth. It begs the questions: Does increased clarity enhance or undermine authenticity? Does it change the meaning of the image?

AI-enhanced Civil War photography isn’t about perfect replication; it’s about interpretation. It’s about using digital tools to reveal what time and decay have obscured. Transparency is crucial. These images should always be accompanied by information about their creation and the assumptions made in their presentation.

Responsibly used, AI becomes a powerful bridge to the past—not rewriting history, but enhancing our vision of it. In careful hands, it can transform faded, two-dimensional relics into vibrant portraits, sparking the imagination of present and future generations.

M.A. Kleen is a program analyst and editor of spirit61.info, a digital encyclopedia of early Civil War Virginia. His article “‘A Kind of Dreamland’: Upshur County, WV at the Dawn of Civil War” was recently published in the Spring 2025 issue of Ohio Valley History.

Endnotes:

[1] Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

[2] National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

[3] Norma Stevens, Avedon: Something Personal (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2017), 600.

[4] Charles Leib, Nine Months in the Quartermaster’s Department; or the Chances for Making a Million (Cincinnati: Moore, Wilstach, Keys & Co., 1862), 92-93.

I teach photography. Advanced black and white film printing to be exact. Professionally I dont like the AI enhancements. I want to see the original. That historical moment when the shutter was released. That is the beauty and the importance of a photograph. Capturing the moment that is like no other and will never be anything else.

I don’t think anything will ever replace the originals, but AI offers something extra. I understand that restoration wasn’t the subject of my post, but it does have incredible capabilities to repair faded or damaged photos.

thanks for this interesting and provocative piece … historians should regard the original photo as a primary source … something created — typically a written record or in this case a photograph — by a period participant … AI on other hand “interprets” the primary source making it a secondary source … that’s an important distinction … the author who uses AI should document the difference so the reader understands what they’re seeing.

Your photo of MG Thomas is a case in point … AI breathed a little too much life into the Rock of Chickamauga — his facial features are different, his sword belt is a weird creation (as you note), and ChatGPT turned the general into a second lieutenant.

Appreciate it, good observations

There are possibilites, but “guesses” on details could be reduced by a bit of research in surviving accoutrements. I’m sure that a uniform coat of Lee might have survived that would put to rest once and for all whether his coat was butternut brown or cadet gray.

An excellent piece, and you got it right – “responsibly used.” I think the technology is still very much in its infancy, and most of the things I’ve seen tend to look like paintings; ironic, because quite often in the day some red pigment was added to photos to brighten faces. The photos of my ancestor on his wedding day and his close friend, in uniform, that were used in memorial cards after they were killed beside each other in battle have this alteration – and it looks like paintings. Perhaps even with this, the more things change the more they stay the same…

Thank you! As you point out, sometimes these vintage photos have been heavily “edited” with things like added pigments. I think AI will eventually get to a point where it can apply color to black and white images in a convincing way, without altering them. It may already be able to and I’m just not aware of it

I still think of that term “Garbage in, garbage out” when it comes to these things. AI has a long, long way to go, and it will no doubt be used for mischief and worse like all ‘advances’ tend to be. However, to be fair, I remember seeing the results of efforts to do things like ‘colorize’ black and white films and pictures. Before computers became so widespread, those efforts required utilizing different methodologies to attain the desired results. Some of those results were quite good, others not so much. I think its possible that use of AI will result in rules, laws, and/ or protocols that require anything being subjected to AI ‘treatment’ must be identified as such. We shall see I reckon.