Ellsworth, Embalming, and the Birth of the Modern American Funeral

ECW welcomes back guest author Jarred Marlowe.

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth was just twenty-four years old when he was killed in May 1861, but his death marked a turning point in how the nation came to view both the war and the way it honored the fallen. Ellsworth was not just any officer. He was a close friend of President Abraham Lincoln, a rising star, and the first Union officer to die in the Civil War. His death not only stirred patriotic fervor across the North, but also sparked a quiet revolution in how Americans preserved and mourned their dead.

Ellsworth commanded the 11th New York Infantry, better known as the Fire Zouaves, a colorful and hard-fighting regiment made up largely of New York City firefighters. On May 24, just a day after Virginia officially seceded, Ellsworth and his men crossed the Potomac River and entered Alexandria to secure the city. While there, he spotted a massive Confederate flag flying from the roof of the Marshall House Inn. The banner had been visible from the White House itself, a public provocation that had infuriated Lincoln and others in Washington.

Ellsworth climbed the stairs to the roof with a handful of soldiers, cut down the flag himself, and was descending with it in hand when the innkeeper, James Jackson, shot him dead at close range. One of Ellsworth’s men, Pvt. Francis Brownell, immediately fired back and killed Jackson on the spot.

Word of Ellsworth’s death reached Washington very quickly. Among those deeply moved was Dr. Thomas Holmes, a New York physician who had been experimenting with embalming. Holmes used his connection with Secretary of State William Seward to gain access to the White House. There, he found President Lincoln in tears. Ellsworth had once worked as Lincoln’s law clerk in Springfield and had accompanied him on the tense inaugural train ride to the capital.

Holmes asked for permission to embalm Ellsworth’s body so it could be returned to his family. At the time, embalming was almost unknown in the United States. Railroads only agreed to transport dead bodies that were either embalmed or placed in sealed Fisk metallic coffins, which were rare and prohibitively expensive due to wartime shortages. Lincoln, unfamiliar with the process, agreed.

Ellsworth’s body was brought back up the Potomac River aboard the steamer James Gray and taken to the Washington Navy Yard. His remains were then placed in an engine house, a symbolic gesture, as many of his men had been recruited from the firehouses of New York. There, following an autopsy, Holmes performed the embalming procedure. The results were striking. Ellsworth’s features were preserved so well that when Mary Todd Lincoln saw him, she whispered to her husband that Ellsworth looked as if he were only sleeping.

Lincoln asked that Ellsworth be laid in state in the East Room of the White House. Around six hundred guests, including politicians, military officers, and foreign dignitaries, attended the funeral. The peaceful appearance of Ellsworth’s body made a lasting impression. For the first time, the American public began to understand the possibilities of embalming as a way to preserve dignity and create meaningful farewells.

Dr. Holmes went on to embalm more than four thousand soldiers and officers during the war, earning him the title “Father of American Embalming.” Although the technique had been introduced earlier by French chemist Jean Nicolas Gannal, it had never taken hold in the United States until war made it a necessity. Another Frenchman, Dr. Jean Pierre Sucquet, had developed a more effective formula using zinc chloride, which was later licensed in the United States by a Manhattan dentist named Dr. Charles Brown.

Ellsworth’s death left a lasting influence beyond the battlefield. Less than a year later, the Lincoln family experienced personal tragedy when young Willie Lincoln died of typhoid fever. Remembering the appearance of Ellsworth, the Lincolns asked for Willie to be embalmed as well. one of the first instances of embalming being used for domestic rather than military purposes. The procedure was performed by Henry Cattell, who worked for Dr. Brown and used Sucquet’s zinc chloride method.

Although Holmes was not called, likely because he was in the field following the armies, his contribution had already helped shape a new cultural understanding of death and mourning. By the end of the war, embalming had become the only practical means to send fallen soldiers home to their families. Still, only about 6 percent of the more than six hundred fifty thousand war dead were embalmed, meaning most families never saw their sons again.

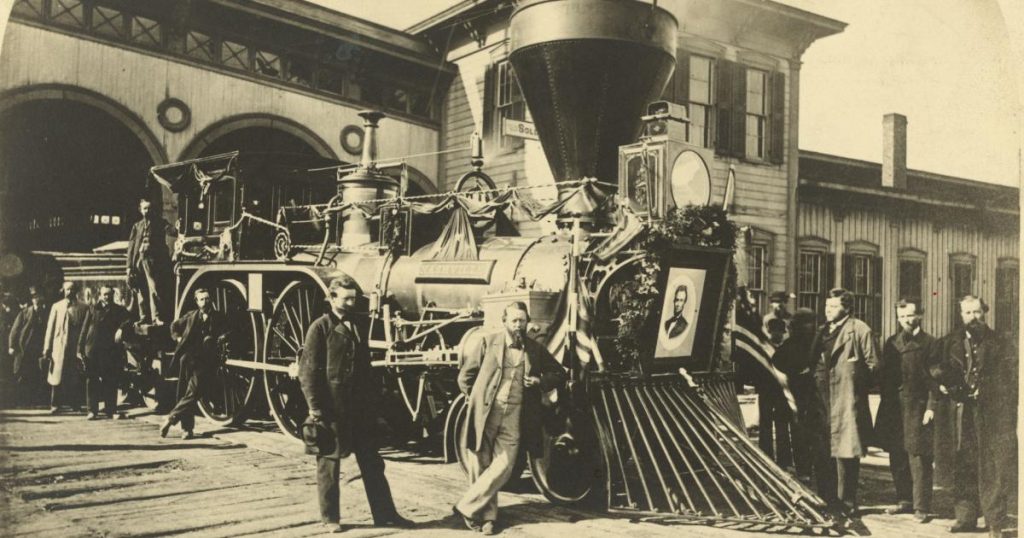

The innovations in embalming that emerged during the war made something else possible: the Lincoln Funeral Train. After the president was assassinated in April 1865, his embalmed body was placed aboard a specially arranged train that traveled more than sixteen hundred miles through seven states. At each stop, thousands of mourners filed past his open casket. The only reason this journey could happen was because embalming preserved Lincoln’s remains long enough for the nation to collectively grieve. Without the techniques Holmes helped popularize with Ellsworth, that level of national mourning and ceremony would not have been possible.

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth died on a staircase in a Virginia inn, but that single moment echoed across the entire war. His death launched a movement that changed how Americans honored the fallen, how they preserved memory, and how they said goodbye.

Jarred Marlowe is a historian who currently lives in Collinsville, Virginia. He has a bachelor’s degree in history from the Virginia Military Institute and master’s degree from Johnson University. Jarred is a member of the Col. George Waller Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution and the Social Media Director of the Blue & Gray Education Society.

Bibliography:

- Meg Groeling, The Aftermath of Battle: The Burial of the Civil War Dead (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2015).

- Meg Groeling, First Fallen: The Life of Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, the North’s First Civil War Hero (El Dorado Hills: Savas Beatie, 2021).

- Todd Harra, “The History and Evolution of American Funeral Practices,” Youtube. Speech. Accessed June 24, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QAS3N__ECl4.

There was no embalming of James Jackson. His dead body was beaten, thrown down the stairway and pinned to the floor of the hotel entrance with multiple bayonets. One southern diarist wrote that he threw his life away.

One more comment, regarding Lincoln’s embalmed body and possibly the work of the embalmer. I pass this on although to you it is anecdotal. My mother reported to me that she spoke to an old man who as a child had witnessed Lincoln in his open casket. Lincoln had a very sad look on his face.