War of Words: John Greenleaf Whittier and the Marais des Cygnes Massacre

ECW welcomes back guest author Keith Moore.

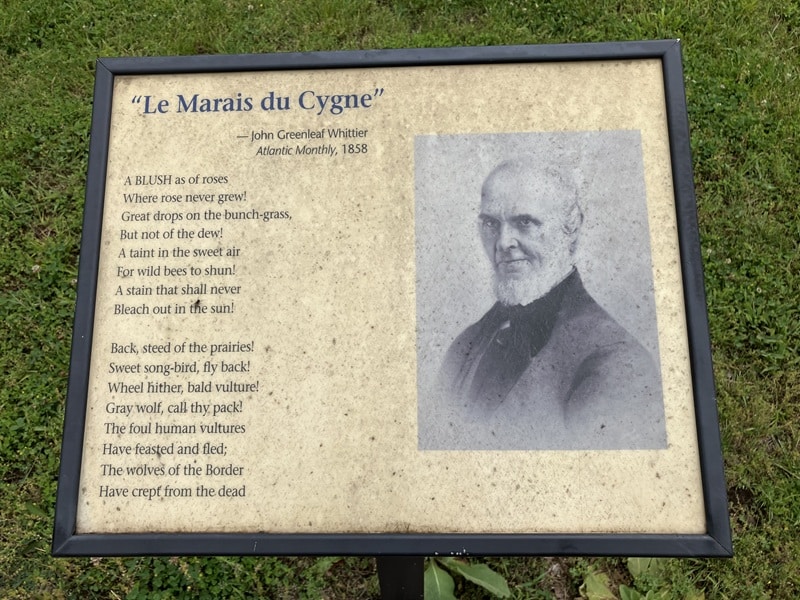

John Greenleaf Whittier took the saying “sometimes the pen is mightier than the sword” to heart. His September 1858 poem, “Le Marais du Cygne,” a blistering rebuke of a violent pro-slavery ambush that occurred four months prior in Linn County, Kansas, became a rallying cry for abolitionists across the country. In the end, it wasn’t a weapon that illuminated the growing unrest in what was then the Kansas Territory, but rather a 342-word, 72-line, nine-stanza poem.

Born in December 1807 in Haverhill, Massachusetts, Whittier published his first poem in 1826 while still in high school. He found work as a shoemaker and teacher before pursuing a full-time career as an editor. He wrote for a handful of New England-based magazines and newspapers, including American Manufacturer, Essex Transcript, Middlesex Standard, National Philanthropist, and New England Weekly Review.[1]

It was during this period that Whittier increasingly turned his attention to abolitionism (largely influenced by his Quaker upbringing).1 He was a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society and signed the Anti-Slavery Declaration of 1833. His early writings, which feature several pamphlets and essays denouncing slavery, include Justice and Expediency (1833) and The Black Man (1845). He also penned two books of anti-slavery poetry: Poems Written during the Progress of the Abolition Question in the United States (1837) and Voices of Freedom (1846).

Whittier’s work as an abolitionist and poet only intensified as the nation entered a period of civil unrest. He served as an elector for Abraham Lincoln in the presidential elections of 1860 and 1864 and continued to write, successfully publishing single poems — At Port Royal 1861 and Song of the Negro Boatmen, for example — and a book titled In War Time and Other Poems (1864).

It was an incident that transpired some 1,500 miles from his New England home, however, that raised Whittier’s literary profile. “Le Marais du Cygne” (French for Marsh of the Swans) became one of the writer’s most famous and important poems.

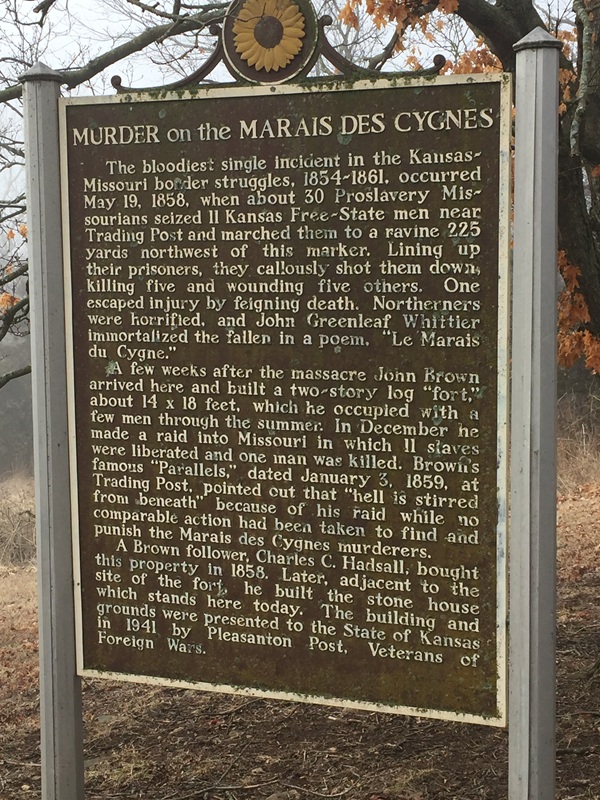

The Marais des Cygnes Massacre occurred on May 19, 1858, in Linn County, Kansas. The attack, in which unarmed anti-slavery men were shot by some two dozen pro-slavery Missourians, is considered one of the single bloodiest incidents in the border struggle between Kansas Territory and the state of Missouri.

Seeking retribution for a previous, unrelated incident, Charles Hamilton, a Georgia native, led a group of pro-slavery men into an area near Trading Post, Kansas. Here, they abducted 11 free-state settlers from their homes and forced them into a ravine. Hamilton and his men then opened fire. Five of the settlers died; five others were wounded, and only one escaped unharmed. The victims were then robbed and left for dead.[2]

The free-state response was swift. Abolitionist John Brown arrived at the site several weeks after the massacre and built a small fort. From there he organized a raid into Missouri that freed almost a dozen slaves and killed one man.[3] However, Hamilton and those responsible for the murder at Marais des Cygnes remained at large.

While Brown and his men took up arms, Whittier grabbed a pen. “Le Marais du Cygne,” a lengthy poem detailing the massacre and memorializing its victims, was first published in September 1858 in The Atlantic Monthly. The incident itself is described in these two stanzas:

From the hearths of their cabins,

The fields of their corn,

Unwarned and unweaponed,

The victims were torn,

The whirlwind of murder

Swooped up and swept on

To the low, reedy fen-lands,

The Marsh of the Swan.

With a vain plea for mercy

No stout knee was crooked;

In the mouths of the rifles

Right manly they looked.

How paled the May sunshine,

O Marais du Cygne!

On death for the strong life,

On red grass for green![4]

Although far removed from his New England home, the Marais des Cygnes Massacre gave Whittier a voice with which to expose to the nation the violence that gave Bleeding Kansas its name. His poem ends this way, the final lament of “Le Marais du Cygne:”

On the lintels of Kansas

That blood shall not dry

Henceforth the Bad Angel

Shall harmless go by;

Henceforth to the sunset,

Unchecked on her way,

Shall Liberty follow

The march of the day.4

While Whittier’s poem struck a nerve with the public, there was no way to prevent the inevitable. The attack on Fort Sumter almost two and half years later, on Apr. 12, 1861, brought the country’s internal struggle to a head.

With the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, Whittier turned his attention to other topics. He found commercial success — one of his books, Snow-Bound, first published in 1866, reportedly sold some 20,000 copies and earned the writer $10,000[5] — although not everyone was keen on his literary talents. Nathaniel Hawthorne, a fellow New Englander and author of The House of the Seven Gables and The Scarlet Letter, had this to say of Whittier: “I like the man, but have no high opinion either of his poetry or his prose.”

Despite the criticism, Whittier continued to write; he produced almost a dozen books of poetry between 1866 and 1890, including Ballads of New England (1870) and The Pennsylvania Pilgrim (1872). During this time, he was also elected to the American Philosophical Society, a scholarly organization founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin and others.

Today both the John Greenleaf Whittier Homestead in Haverhill, Massachusetts and the John Greenleaf Whittier Home and Museum in Amesbury, Massachusetts honor his memory, as does the John Greenleaf Whittier Bridge (also in Amesbury). His influence can be felt across the country; Whittier, California is named for him, as is that city’s private liberal arts college. Whittier died in New Hampshire in September 1892 at the age of 84.

Keith Moore is a native New Englander with an advanced degree in literature from the University of Oklahoma. His short fiction has appeared in Bluestem Magazine and Ponder Review; his writing has also been published in The Boston Globe and the Cape Cod Times.

Endnotes:

[1] Academy of American Poets, “John Greenleaf Whittier,”

https://poets.org/poet/john-greenleaf-whittier.

[2] Christopher Rein, “Marais des Cygnes Massacre,” Civil War on the Western Border, https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/marais-des-cygnes-massacre.

[3] Kathy Alexander, “Marais des Cygnes Massacre, Kansas,” Legends of America, Feb. 2023,

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ks-maraisdescygnes/.

[4] John Greenleaf Whittier, “Le Marais du Cygnes,” The Atlantic Monthly, Sept. 1858.

[5] Poetry Foundation, “John Greenleaf Whittier,”

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/john-greenleaf-whittier.

Thanks for this! Didn’t know about this massacre but helps me see why John Brown was so angry and committed the Potawatomi Massacre against pro-slavery men.

“Charles Hamilton, a Georgia native…” Interesting. It appears that at the time of the Civil War, Hamilton was colonel of a Texas regiment and fought with the Army of Northern Virginia, but then returned to his home state and became involved in GA politics, becoming a state legislator. “Charles A. Hamilton – Pro-Slavery Leader,” Legends of Kansas, https://legendsofkansas.com/charles-a-hamilton/#google_vignette; “Charles Hamilton,” Kansas Historical Society, https://www.kansashistory.gov/index.php?url=kansapedia/charles-hamilton/19728

It is interesting because while growing up Margaret Mitchell, of Atlanta, GA, is known to have heard many stories of the War at the knee of CSA veterans and elsewhere. She later chose the name “Charles Hamilton” for one of her characters in Gone With the Wind (Scarlett’s first husband). Coincidence? Perhaps., but interesting.

Thank you for this article, it gave me new insights and am glad you took the effort to create. Interesting fellow, the line, “on the lintels of Kansas that blood shall not dry,” sad event with long term ramifications.